The Overview - October 11, 2021

The Overview is a weekly roundup of eclectic content in-between essay newsletters & 'Conversations' podcast episodes to scratch your brain's curiosity itch.

Hello Eclectic Spacewalkers,

I wish that you and your family are safe and healthy wherever you are in the world. :)

Check out the previous The Overview - September 07, 2021: HERE

Read our latest essay - Technopoly : HERE

Watch/listen to our ‘Conversation with Celine Halioua’: HERE

Get our E-Book for free by using ‘substack’: HERE

—

Below are some eclectic links for the week of October 11th, 2021.

Enjoy, share, and subscribe!

Table of Contents

Theme & Topics: #IndigenousPeoplesDay, Indigenous Peoples & Knowledge, and being honest about past atrocities

Articles/Essays - Last line of defence via Global_Witness (H/T: @bbcmarshall); How Indigenous Knowledge Can Help Us Combat Climate Change via @climatereality; Can Indigenous Leadership Save Our National Parks and Monuments? via @jfkeeler in @Sierra_Magazine; The Red Nation - 10 Point Program via @The_Red_Nation; Land-grab universities via @HighCountryNews; INDIGENOUS RESISTANCE AGAINST CARBON (H/T: @Rileyyesnomaybe); What Gabby Petito’s Case Says About Cops—and Us via @TheDailyBeast; What is a Homestead Commons? Why does it matter? via Chong Kee Tan; Simple hand-built structures can help streams survive wildfires and drought via ScienceNews; Safety is Impossible. Build Protocols of Protection Instead via @dastillman

Books - Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer; An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States by @rdunbaro; Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World by Tyson Yunkaporta

Documentaries - The Indigenous Documentary - A film by Mayra Perdomo; 7 moving documentaries that show Indigenous struggles and successes via @MatadorNetwork

Film/TV - Reservation Dogs (FX on Hulu) via @RezDogsFXonHulu

Lectures - The Vanishing Indian Speaks Back: Race, Genomics, and Indigenous Rights via @MSFTresearch with @kimtallbear; Indigenous Peoples and Technoscience

Paper - A global assessment of Indigenous community engagement in climate research; Too late for indigenous climate justice: Ecological and relational tipping points; Ensuring climate services serve society: examining tribes’ collaborations with climate scientists using a capability approach; INDIGENOUS COSMOPOLITICS IN THE ANDES: Conceptual Reflections beyond “Politics”; Indigenous knowledge and the shackles of wilderness

Podcasts - What if indigenous wisdom could save the world?; Patterns of Creation with Dr. Tyson Yunkaporta | Talk of Today Podcast via @SamHBarton; The Other Others By Tyson Yunkaporta; Give The Land Back? via @flashforwardpod; Indigenous Climate Knowledges and Data Sovereignty

TED Talks - Indigenous Peoples: A collection of 35 TED Talks (and more) on the topic of Indigenous peoples.

Twittersphere - Where can you find Indigenous philosophy?; let’s honor the Indigenous communities leading the movement for climate action and environmental justice; we’ll be co-hosting the very first congress, #OurLandOurNature, to discuss how to #DecolonizeConservation, as an alternative to the #IUCNcongress; for me wilderness is a settler-colonial concept that erases Indigenous sovereignty; Around 1100 AD, European Vikings met Native Americans in Newfoundland, and Native Americans met with Polynesians on Fatu Hiva island; a thread of films that feature Indigenous Peoples; From 1830 to 1890, 30 million bison were reduced to less than 1,000.

Videos (Short) - Why the IK Systems Lab matters, (Video 1) Original Indigenous Economies: Then and Now, (Video 2) Colonialism: Then and Now, (Video 3) A New Path Forward

Websites - Indigenous STS; Indigenous Knowledge Institute; The Indigenous Knowledges Systems Lab; Yellowhead Institute; The Red Nation

Articles/Essays

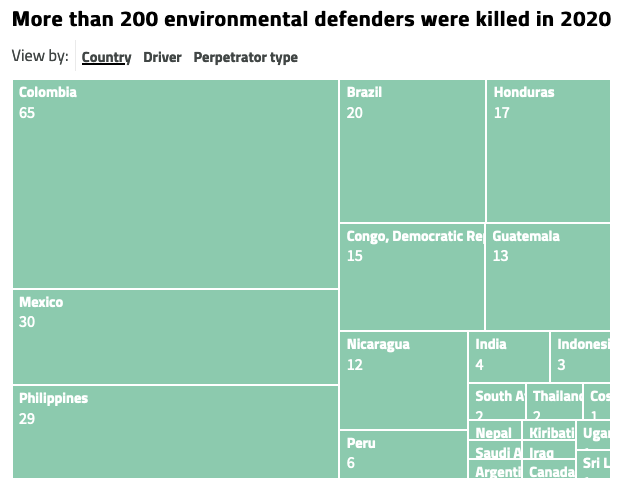

Last line of defence via Global_Witness (H/T: @bbcmarshall)

“The climate crisis is a crisis against humanity.

Since 2012, Global Witness has been gathering data on killings of land and environmental defenders. In that time, a grim picture has come into focus – with the evidence suggesting that as the climate crisis intensifies, violence against those protecting their land and our planet also increases. It has become clear that the unaccountable exploitation and greed driving the climate crisis is also driving violence against land and environmental defenders.

In 2020, we recorded 227 lethal attacks – an average of more than four people a week – making it once again the most dangerous year on record for people defending their homes, land and livelihoods, and ecosystems vital for biodiversity and the climate.

As ever, these lethal attacks are taking place in the context of a wider range of threats against defenders including intimidation, surveillance, sexual violence, and criminalisation. Our figures are almost certainly an underestimate, with many attacks against defenders going unreported. You can find more information on our verification criteria and methodology in the full report…

An unequal impact

Much like the impacts of the climate crisis itself, the impacts of violence against land and environmental defenders are not felt evenly across the world. The Global South is suffering the most immediate consequences of global warming on all fronts, and in 2020 all but one of the 227 recorded killings of defenders took place in the countries of the Global South.

The disproportionate number of attacks against Indigenous peoples continued, with over a third of all fatal attacks targeting Indigenous people – even though Indigenous communities make up only 5% of the world’s population. Indigenous peoples were also the target of 5 out of the 7 mass killings recorded in 2020.

As has been the case in previous years, in 2020 almost 9 in 10 of the victims of lethal attacks were men. At the same time, women who act and speak out also face gender-specific forms of violence, including sexual violence. Women often have a twin challenge: the public struggle to protect their land, and the less-visible struggle to defend their right to speak within their communities and families.”

—

How Indigenous Knowledge Can Help Us Combat Climate Change via @climatereality

“Indigenous communities have a wealth of knowledge that can make climate change mitigation and adaptation more effective. We just have to listen.

The Need for Indigenous Voices in Climate Change Discussions

More and more, the climate movement is recognizing that Indigenous knowledge on climate change mitigation and adaptation can benefit the world. Even the IPCC said so.

Despite the valuable knowledge they possess, Indigenous communities, who are also some of the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, have largely been left out of formal discussions on these topics.

The role Indigenous peoples play in preventing deforestation and land degradation has long been ignored. Case in point: the discussions for the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. One key target of the framework calls to double protected areas to 30% globally. While this sounds like a good thing, how do these policies actually affect Indigenous and local communities?

Studies have also shown that deforestation rates are lower in forests that Indigenous peoples manage and control than in protected areas where strict conservation is enforced. In fact, protected areas can be harmful to Indigenous communities, as they’ve historically pushed Indigenous peoples off of their land. The same land that they depend on for their food, livelihoods, and cultural identities.

While Indigenous rights have been increasingly recognized at the international level, they’re not always respected on the national level. To successfully combat climate change and achieve climate justice, Indigenous peoples must be part of the conversation and the action at all levels of the government.”

Recent Example

Indigenous knowledge the cornerstone of new tsunami modelling for Vancouver Island's northwest coast: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/tsunami-modelling-results-1.6204268?cmp=rss

The Long-Lost Tale of an 18th-Century Tsunami, as Told by Trees: https://www.wired.com/story/the-long-lost-tale-of-an-18th-century-tsunami-as-told-by-trees/#intcid=_wired-homepage-right-rail_4b3aa66f-2f09-4c4b-902d-48281597316e_popular4-1

—

Can Indigenous Leadership Save Our National Parks and Monuments? via @jfkeeler in @Sierra_Magazine

“When I looked into the buffalo’s eyes that day near Old Faithful, I did not think of my ancestors. These expansive connections to the land are difficult to comprehend living as we do in our reduced circumstances on reservations. The ongoing US occupation of our homelands makes our worlds smaller; it restricts how we imagine what we once were and what we could be.

As we drove through Yellowstone, my middle-school-age daughter pointed out places she recognized from playing the video game Wolfquest when she was younger. She had spent years role-playing being a member of a gray wolf pack raising pups and surviving on the digitally re-created landscape. In the 21st century, displaced and removed from our homelands, this is how Sunka Isnala’s five-times-great-granddaughter now knows the place where he was born.

How we heal from this history is in our hands now today. Are we willing to take steps to do so even if it outrages the part of America represented by the Republican Party?

For the first time, Native Americans like Secretary Haaland now hold key positions in power over large swathes of territory in the United States. The potential leadership of tribal leaders like Chuck Sams, whose training is tribally management focused, may offer a glimmer of what a new inclusive future for America could look like. Could it save the world from climate change? Could it save us from the political rural-urban divide we see today? Could it make us one people genuinely tied to the land and not colonial systems of exploitation? We will only know if we try. We only may get this chance.”

—

The Red Nation - 10 Point Program via @The_Red_Nation

WE DEMAND AN END TO VIOLENCE AGAINST NATIVE PEOPLES AND OUR NONHUMAN RELATIVES THROUGH…

1. The Re-Instatement of Treaty Rights

From 1776 to 1871, the U.S. Congress ratified more than 300 treaties with Native Nations. A provision in the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act withdrew federal recognition of Native Nations as separate political entities, contracted through treaties made with the United States. As a result, treaty making was abolished; and it was established that “no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty.”

We demand the reinstatement of treaty making and the acknowledgement of Native independence. We demand Native Nations assume their rightful place as independent Nations guaranteed the fundamental right to self-determination for their people, communities, land bases, and political and economic systems.

2. The Full Rights and Equal Protection for Native People

Centuries of forced relocation and land dispossession have resulted in the mass displacement of Native Nations and peoples from their original and ancestral homelands. Today in the United States four of five Native people do not live within reservation or federal trust land. Many were and are forced to leave reservation and trust lands as economic and political refugees due to high unemployment, government policies, loss of land, lack of infrastructure, and social violence. Yet, off-reservation Native peoples encounter equally high rates of sexual and physical violence, homelessness, incarceration, poverty, discrimination, and economic exploitation in cities and rural border towns.

We demand that treaty rights and Indigenous rights be applied and upheld both on- and off-reservation and federal trust land. All of North America, the Western Hemisphere, and the Pacific is Indigenous land. Our rights do not begin or end at imposed imperial borders we did not create nor give our consent to. Rights shall be enforced pursuant to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the historical and political doctrines of specific Tribes.

3. The End to Disciplinary Violence Against Native Peoples and All Oppressed Peoples

In the United States more than three million people are incarcerated in the largest prison system in the world. Native peoples and oppressed peoples are disproportionately incarcerated and persecuted by law enforcement. Within this system Native peoples are the group most likely to be murdered and harassed by law enforcement and to experience high rates of incarceration. This proves that the system is inherently racist and disciplines politically disenfranchised people to keep them oppressed and prevent them from challenging institutions of racism like prisons, police and the law that maintain the status quo. Racist disciplinary institutions contribute to the continued dispossession and death of Native peoples and lifeways in North America.

We demand an end to the racist and violent policing of Native peoples on- and off-reservation and federal trust lands. We demand an end to the racist state institutions that unjustly target and imprison Native peoples and all oppressed peoples.

4. The End to Discrimination Against the Native Silent Majority: Youth and The Poor

Native youth and Native poor and homeless experience oppression and violence at rates higher than other classes and groups of Native peoples. Native people experience homelessness and poverty at rates higher than other groups and Native youth suicide and criminalization rates continue to soar. Native youth now comprise as much as 70% of the Native population in some places. Native youth in the U.S. experience rates of physical and sexual violence and posttraumatic stress disorder higher than other groups. Native poor and homeless experience rates of criminalization, alcoholism, and violence at higher rates than other groups. Because many Native youth and Native homeless and poor live off reservation and trust lands, they are treated as inauthentic and without rights. Native youth and Native poor and homeless continue to be marginalized and ignored within Native and dominant political systems, and within mainstream social justice approaches.

We demand an end to the silencing and blaming of Native youth and Native poor and homeless. We demand an end to the unjust violence and policing they experience. Native youth and Native poor and homeless are relatives who deserve support and representation. We demand they be at the center of Native struggles for liberation.

5. The End to the Discrimination, Persecution, Killing, Torture, and Rape of Native Women

Native women are the targets of legal, political, and extra-legal persecution, killing, rape, torture, discrimination, and disenfranchisement in North America. This is part of the ongoing process of eliminating women’s political and customary roles as leaders in Native societies. In the United States more than one in three Native women will be raped in their lifetime, often as children. Since 1980, about 1,200 Native women have gone missing or been murdered in Canada; many are young girls. Native women are at higher risk of being targeted for human trafficking and sexual exploitation than other groups. Native women continue to experience sexism and marginalization within Native and dominant political systems, and within mainstream social justice approaches.

We demand the end to the legal, political, and extra-legal discrimination, persecution, killing, torture, and rape of Native women. Women are the backbone of our political and customary government systems. They give and represent life and vitality. We demand that Native women be at the center of Native struggles for liberation.

6. The End to the Discrimination, Persecution, Killing, Torture, and Rape of Native Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Two-Spirit People

Native LGBTQ2 people experience persecution, killing, torture, and rape within Native Nations and within dominant society. The processes of colonization and heteropatriarchy impose binary gender roles, nuclear family structures, and male-dominated hierarchies that are fundamentally at odds with Native customary laws and social organization, where LGBTQ2 people often held positions of privilege and esteem. The effect of this system for Native LGBTQ2 is violent. Native LGBTQ2 experience rates of murder, sexual exploitation, discrimination, hate crimes, homelessness and substance abuse at high rates. Like Native youth, poor and homeless, and women, Native LGBTQ2 continue to be marginalized and ignored within Native and dominant political systems, and within metropolitan-based social justice approaches that ignore the mostly rural-based issues of Native LGBTQ2.

We demand the end to the legal, political, and extra-legal discrimination, persecution, killing, torture, and rape of Native LGBTQ2 in Native societies and in dominant society. Native LGBTQ2 are relatives who deserve representation and dignity. We demand that they be at the center of Native struggles for liberation.

7. The End to the Dehumanization of Native Peoples

The appropriation of Native imagery and culture for entertainment, such as sports mascots and other racist portrayals, and the celebration of genocide for holidays and amusement, such as Columbus Day and Thanksgiving, dehumanize Native people and attempt to whitewash ongoing histories of genocide and dispossession. These appropriations contribute to the ongoing erasure of Native peoples and seek to minimize the harsh realities and histories of colonization. These appropriations are crimes against history.

We demand an end to the dehumanization of Native peoples through cultural appropriation, racist imagery, and the celebrations of genocide and colonization. Condemning symbolic and representational violence is an essential part of any material struggle for liberation.

8. Access to Appropriate Education, Healthcare, Social Services, Employment, and Housing

Access to quality education, healthcare, social services, and housing are fundamental human rights. However, in almost every quality of life standard, Native people have the worst access to adequate educational opportunities, health care, social services, and housing in North America. Native people also have the highest rates of unemployment both on- and off-reservation than any other group in the United States. Access to meaningful standards of living is historically guaranteed under many treaty rights, but have been consistently ignored and unevenly applied across geography and region.

We demand the universal enforcement and application of services to improve the standard of living for Native peoples pursuant to provisions in treaties and the UNDRIP, whether such peoples reside on or off reservation and trust lands. North America is our home and we demand more than mere survival. We demand conditions to thrive.

9. The Repatriation of Native Lands and Lives and the Protection of Nonhuman Relatives

The ethical treatment of the land and nonhuman relatives begins with how we act. We must first be afforded dignified lives as Native peoples who are free to perform our purpose as stewards of life if we are to protect and respect our nonhuman relatives—the land, the water, the plants, and the animals. We must have the freedom and health necessary to make just, ethical and thoughtful decisions to uphold life. We experience the destruction and violation of our nonhuman relatives wrought by militarization, toxic dumping and contamination, and resource extraction as violent. Humans perpetrate this violence against our nonhuman relatives. We will be unable to live on our lands and continue on as beings recognized by the spirits if this violence is allowed to continue.

We demand an end to all corporate and U.S. control of Native land and resources. We demand an end to Tribal collusion with such practices. We demand that Points 1-8 be enforced so as to allow Native peoples to live in accordance with their purpose as human beings who protect and respect life. Humans have created this crisis and continue to wage horrific violence against our nonhuman relatives. It is our responsibility to change this. We demand action now.

10. The End to Capitalism-Colonialism

Native people are under constant assault by a capitalist-colonial logic that seeks the erasure of non-capitalist ways of life. Colonial economies interrupt cooperation and association and force people instead into hierarchical relations with agents of colonial authority who function as a permanent occupying force on Native lands. These agents are in place to enforce and discipline Native peoples to ensure that we comply with capitalist-colonial logics. There are many methods and agents of enforcement and discipline. There are the police. There are corporations. There are also so-called ‘normal’ social and cultural practices like male-dominance, heterosexuality, and individualism that encourage us to conform to the common sense of capitalism-colonialism. These are all violent forms of social control and invasion that extract life from Natives and other oppressed peoples in order to increase profit margins and consolidate power in the hands of wealthy nation-states like the United States. The whole system depends on violence to facilitate the accumulation of wealth and power and to suppress other, non-capitalist ways of life that might challenge dominant modes of power. Political possibilities for Native liberation therefore cannot emerge from forms of economic or institutional development, even if these are Tribally controlled under the guise of ‘self-determination’ or ‘culture.’ They can only emerge from directly challenging the capitalist-colonial system of power through collective struggle and resistance.

We demand the end to capitalism-colonialism on a global level. Native peoples, youth, poor and homeless, women, LGBTQ2 and nonhuman relatives experience extreme and regular forms of violence because the whole system relies on our death. Capitalism-colonialism means death for Native peoples. For Native peoples to live, capitalism and colonialism must die.”

The Red Nation Manifesto: https://therednationdotorg.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/trn-pamphlet-manifesto-edits.pdf

—

Land-grab universities via @HighCountryNews

Expropriated Indigenous land is the foundation of the land-grant university system.

So how do you steer the conversation to the facts and not the myth?This is what we know: Hundreds of violence-backed treaties and seizures extinguished Indigenous title to over 2 billion acres of the United States. Nearly 11 million of those acres were used to launch 52 land-grant institutions. The money has been on the books ever since, earning interest, while a dozen or more of those universities still generate revenue from unsold lands. Meanwhile, Indigenous people remain largely absent from student populations, staff, faculty and even curriculum.

“Having a conversation about the colonial foundations of those nation states really complicates those narratives, and it starts to bring into question our very right to be here and our right to make claims on this place and on the institutions that we are generally so attached to.”

In this context, Indigenous people are an inconvenient truth. If you look at the law and the treaties, then you raise an existential question about the United States and its very right to be here. It’s a question most people would rather ignore.

Try this scenario, devised by Cutcha Risling Baldy (Hupa/Yurok/Karuk) as a way for her students to better envision the dilemma. She’s the department chair of Native American studies at Humboldt State University in California.Imagine this: Your roommate’s boyfriend comes in one day and steals your computer. He uses it in front of you, and when you point out it’s your computer, not his, he disagrees. He found it. You weren’t using it. It’s his.

“How long until you can let that go?” she said. “How long until you’re like, ‘Never mind, I guess that’s your computer now.’ ’’Now imagine that’s what happened to your land.

“How long are we supposed to not say, ‘This is the land that you stole, so you don’t get to claim ownership of it, and then feel really proud of yourself that you’re using it for education?’ ’’ Baldy said.

In fact, the evidence of Indigenous dispossession and the role of land-grant universities in that expropriation has been hiding in plain sight.“Whether they realize it or not, every person who’s ever gone through 4-H in America owes that experience to the benefits of the land-grant system,” said Barry Dunn (Rosebud Sioux), president of South Dakota State University. “And the land-grant system has, at its core, the land that was provided.”

—

INDIGENOUS RESISTANCE AGAINST CARBON (H/T: @Rileyyesnomaybe)

"Indigenous resistance has stopped or delayed GHG pollution equivalent to at least one-quarter of annual U.S. and Canadian emissions.

Indigenous Resistance Against Carbon seeks to uplift the work of countless Tribal Nations, Indigenous water protectors, land defenders, pipeline fighters, and many other grassroots formations who have dedicated their lives to defending the sacredness of Mother Earth and protecting their inherent rights of Indigenous sovereignty and self- determination. In this effort, Indigenous Peoples have developed highly effective campaigns that utilize a blended mix of non-violent direct action, political lobbying, multimedia, divestment, and other tactics to accomplish victories in the fight against neoliberal projects that seek to destroy our world via extraction.

In this report, we demonstrate the tangible impact these Indigenous campaigns of resistance have had in the fight against fossil fuel expansion across what is currently called Canada and the United States of America. More specifically, we quantify the metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions that have either been stopped or delayed in the past decade due to the brave actions of Indigenous land defenders. Adding up the total, Indigenous resistance has stopped or delayed greenhouse gas pollution equivalent to at least one-quarter of annual U.S. and Canadian emissions.”

—

What Gabby Petito’s Case Says About Cops—and Us via @TheDailyBeast

“Gabby Petito’s hashtag was searched 268 million times on TikTok. In the same area that Gabby Petito disappeared, 710 indigenous people— mostly girls—disappeared between the years of 2011 and 2020 but their stories didn’t lead news cycles, internet sleuths didn’t clog Instagram and Twitter trying to solve the mystery of their disappearances. Personally, I find it more than a little infuriating that those 710 people didn’t get the same attention as this white, model-thin 22-year-old who’d been documenting her travels through Utah’s national parks in a white van with her boyfriend on Instagram.

While her story has resonated on many levels—to some she is an abused girlfriend, to others the victim of a serial killer of the kind you might find in a cold case podcast series (two newlywed women were murdered in Moab at around the same time as Petito came to town), and many of us see proof in this story of how police often don’t take domestic violence as seriously as they should.”

—

What is a Homestead Commons? Why does it matter? via Chong Kee Tan

“The Homestead Commons: A homestead Commons is a community of value-aligned people homesteading collaboratively to achieve the goals of self-sufficiency, environmental stewardship, and non-exploitative relationship. In the best case scenario, enough people choosing to live like this may help to avert some of the worst climate and social collapse looming very close in our future. In the average case, these communities may serve as oases for surviving the mayhem that ensues after the great collapse. In the worst case, it is a way for us to live in integrity with our deepest values, even when humanity eventually becomes extinct.

In its fullest manifestation, a homestead commons is the same as the fullest manifestation of an eco-village. The difference is that eco-villages usually start from solving the problem of affordable housing and carbon footprint reduction, and work towards self-sufficiency, oftentimes still needing to buy and sell into the capitalist market in order to function. Whereas homestead commons start from regenerative self-sufficiency which also takes care of affordable housing and carbon footprint reduction, and work towards decoupling from capitalism as much as possible. The danger of needing the larger capitalist economy to survive is that when the great collapse comes, you may become another collateral damage. Whereas if you are constantly trying to be less and less reliant on the capitalist economy, you will be less affected when it collapses.

Naturally, no one can be immediately and completely decoupled from the larger capitalist economy right now. But there is nothing stopping us from intelligently weaning ourselves from it, one small step at a time.”

—

Simple hand-built structures can help streams survive wildfires and drought via ScienceNews

Low-tech restoration gains popularity as an effective fix for ailing waterways in the American West

“Wilde realized this was partly because his family and neighbors, like generations of American settlers before them, had trapped and removed most of the dam-building beavers. The settlers also built roads, cut trees, mined streams, overgrazed livestock and created flood-control and irrigation structures, all of which changed the plumbing of watersheds like Birch Creek’s.

Many of the wetlands in the western United States have disappeared since the 1700s. California has lost an astonishing 90 percent of its wetlands, which includes streamsides, wet meadows and ponds. In Nevada, Idaho and Colorado, more than 50 percent of wetlands have vanished. Precious wet habitats now make up just 2 percent of the arid West — and those remaining wet places are struggling.

Nearly half of U.S. streams are in poor condition, unable to fully sustain wildlife and people, says Jeremy Maestas, a sagebrush ecosystem specialist with the NRCS who organized that workshop on Wilde’s ranch in 2016. As communities in the American West face increasing water shortages, more frequent and larger wildfires (SN: 9/26/20, p. 12) and unpredictable floods, restoring ailing waterways is becoming a necessity.”

—

Safety is Impossible. Build Protocols of Protection Instead via @dastillman

I believe that psychological safety is essential for groups and organizations to do their best work. And I’m not alone. Google has studied it, books have been written about it. Even little old me has written about it. In my men’s work we talk about creating safety for ourselves first, so we can do it for others. And I stand by that point of view.

I also stand by the work on safety I did with a wonderful group of Sprint Leaders at Google Relay, which explored the future of the Design Sprint for its 10-year anniversary. Working with the Google Sprint team for the last several years has been one of the highlights of my career. Every time we collaborate, they push me to go deeper and find something more real, honest and true in my work. This time was no different.

My team designed a "safety manual" with some amazing resources (including one of my recent favorites: Dr. Lesley Ann Noel’s Positionality Wheel – a powerful way to build safety through acknowledging diversity)

But what if it’s actually impossible to create safety?

Protection over Safety

How to Say “Sorry” in Four Easy Steps

If you have caused someone offense, and you’d like to repair the relationship, an apology is in order. The Greater Good in Action (GGIA) project works to synthesize the best science on how to live a good life. On its site, GGIA cites a delightful study titled “An Exploration of the Structure of Effective Apologies” outlined here:

1. Acknowledge the offense. “I made a mistake” is much more effective than “mistakes were made.” Be specific.

2. Provide an explanation. Backstory or context can help, but making an excuse or minimizing the harm another person feels will backfire. If you want to hear the formula in action, there’s a lovely podcast episode from the GGIA here.

3. Express remorse. You might feel bad for hurting another person; sharing that remorse can help build empathy.

4. Make amends. Don’t stop with feeling sorry. Offer to do something about the mess you’ve made. That’s the essence of repairing the error. Ask what might make them feel better rather than assuming you know. Make the offer specific and tangible.

The study showed that the acknowledgment of responsibility (#1) and an offer of repair (#4) were the most important elements. A word of caution: Don’t try to fake an apology, even with this guide!

Recently, someone pointed out that this process is very similar to Ho'oponopono, an ancient Hawaiian spiritual practice that involves:

“learning to heal all things by accepting "Total Responsibility" for everything that surrounds us – confession, repentance, and reconciliation.”

For your teams, for your organization, for your family - establish protocols of protection. Watch each other’s backs, and speak up when you see or feel harm. Then...allow someone to apologize and offer forgiveness if you can - which is much harder than apologizing.”

Books

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer

“I could hand you a braid of sweetgrass, as thick and shining as the plait that hung down my grandmother’s back. But it is not mine to give, nor yours to take. Wiingaask belongs to herself. So I offer, in its place, a braid of stories meant to heal our relationship with the world. This braid is woven from three three strands: Indigenious ways of knowing, scientific knowledge, and the story of Anishinabekwe scientist trying to bring them together in service to what matters most. It is an interwining of science, spirit, and story--old stories and new ones that can be medicine for our broken relationship with earth, a pharmacolopoeia of healing stories that allow us to imagine a different relationship, in which people and land are good medicine for each other.” pg. ix

Planting Sweetgrass

Tending Sweetgrass

Picking Sweetgrass

Braiding Sweetgrass

Burning Sweetgrass

“The moral covenant of reciprocity calls us to honor our responsibilities for all we have been given, for all that we have taken. It’s our turn now, long overdue. Let us hold a giveaway for Mother Earth, spread our blankets our for her and pile them high with gifts of our own making. IMagine the books, the paintings, the poems, the clever machine, the compassionate acts, the transcendent ideas, the perfect tools. The fierce defense of all that has been given. Gifts of mind, hands, heart, voice, and vision all offered up on behalf of the earth. Whatever our gift, we are called to give it and to dance for the renewal of the world.

In return for the privilege of breath.” pg. 384

—

An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States by @rdunbaro

“The history of the United States is a history of settler colonial ism-the founding of a state based on the ideology of white su premacy, the widespread practice of African slavery, and a policy of genocide and land theft. Those who seek history with an upbeat ending, a history of redemption and reconciliation, may look around and observe that such a conclusion is not visible, not even in utopian dreams of a better society. Writing US history from an Indigenous peoples' perspective re quires rethinking the consensual national narrative. That narrative is wrong or deficient, not in its facts, dates, or details but rather in its essence. Inherent in the myth we've been taught is an embrace of settler colonialism and genocide. The myth persists, not for a lack of free speech or poverty of information but rather for an absence of motivation to ask questions that challenge the core of the scripted narrative of the origin story. How might acknowledging the reality of US history work to transform society? That is the central question this book pursues. Teaching Native American studies, I always begin with a simple exercise. I ask students to quickly draw a rough outline of the United States at the time it gained independence from Britain. In variably most draw the approximate present shape of the United States from the Atlantic to the Pacific-the continental territory not fully appropriated until a century after independence. What became independent in 1783 were the thirteen British colonies hugging the Atlantic shore. When called on this, students are embarrassed be cause they know better. I assure them that they are not alone. I call this a Rorschach test of unconscious "manifest destiny," embedded in the minds of nearly everyone in the United States and around the world. This test reflects the seeming inevitability of US extent and power, its destiny, with an implication that the continent had previ ously been terra nullius, a land without people.” pg. 2

The provincialism and national chauvinism of US history production make it difficult for effective revisions to gain authority. Schol ars, both Indigenous and a few non-Indigenous, who attempt to rectify the distortions, are labeled advocates, and their findings are rejected for publication on that basis. Indigenous scholars look to research and thinking that has emerged in the rest of the European colonized world. To understand the historical and current experi ences of Indigenous peoples in the United States, these thinkers and writers draw upon and creatively apply the historical materialism of Marxism, the liberation theology of Latin America, Frantz Fanon's psychosocial analyses of the effects of colonialism on the colonizer and the colonized, and other approaches, including development theory and postmodern theory. While not abandoning insights gained from those sources, due to the "exceptional" nature of US colonialism among nineteenth-century colonial powers, Indigenous scholars and activists are engaged in exploring new approaches.

This book claims to be a history of the United States from an Indigenous peoples' perspective but there is no such thing as a collective Indigenous peoples' perspective, just as there is no mono lithic Asian or European or African peoples' perspective. This is not a history of the vast civilizations and communities that thrived and survived between the Gulf of Mexico and Canada and between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific. Such histories have been written, and are being written by historians of Dine, Lakota, Mohawk, Tlingit, Muskogee, Anishinaabe, Lumbee, Inuit, Kiowa, Cherokee, Hopi, and other Indigenous communities and nations that have survived colonial genocide. This book attempts to tell the story of he United States as a colonialist settler-state, one that, like colonial ist European states, crushed and subjugated the original civilizations in the territories it now rules. Indigenous peoples, now in a colonial relationship with the United States, inhabited and thrived for millennia before they were displaced to fragmented reservations and economically decimated.

This is a history of the United States.”” pg. 13-14

—

Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World by Tyson Yunkaporta

“This remarkable book is about everything from echidnas to evolution, cosmology to cooking, sex and science and spirits to Schrödinger’s cat.

Tyson Yunkaporta looks at global systems from an Indigenous perspective. He asks how contemporary life diverges from the pattern of creation. How does this affect us? How can we do things differently?

Sand Talk provides a template for living. It’s about how lines and symbols and shapes can help us make sense of the world. It’s about how we learn and how we remember. It’s about talking to everybody and listening carefully. It’s about finding different ways to look at things.

Most of all it’s about Indigenous thinking, and how it can save the world.”

Documentaries

The Indigenous Documentary - A film by Mayra Perdomo

“Experience the beauty and wisdom of indigenious cultures through the eyes of a knowledge seeker

The Indigenous Documentary is a docu-series through the eyes of a knowledge seeker. The filmmaker Mayra Perdomo will travel to 17+ Countries including The United States of America to converse with indigenous people and native people who still practice the old ways.

Filming begins in Sedona, Arizona then New York, Connecticut and possibly adding a few other states if time allows before international filming begins. The bulk of the filming will be from October 2021-October 2023 in various countries depending on how Covid-19 is affecting travel in those countries.

In this docu-series, we look to answer a few specific questions that touch upon categories like healing, music, dance, climate change, external interference, duality, history, and inquiry. These categories will be used as a marker to create a segmented docu-series that will be available to view for free as this is a donation-based documentary. If you prefer to see the full-length unedited interview those will be available for purchase.

The purpose is to educate in addition to donating to indigenous charitable causes which are better explained on the About page.

Thank you for your time and we welcome you to join us on this journey.

—

7 moving documentaries that show Indigenous struggles and successes via @MatadorNetwork

“1. What Was Ours

2. Water Warriors

3. The Radicals

4. Lake of Betrayal

5. We Breathe Again

6. We Still Live Here

7. The Refuge

November is Native American Heritage Month. In addition to following Indigenous activists on Instagram and learning about Native food cultures, comprehending the societal and environmental issues facing Indigenous communities is key to better understanding what others of us can do to make the world a more equitable place to live. These seven documentary films offer a glimpse into modern issues faced by the Indigenous peoples of North America. Have a watch. You’ll come out better informed — and inspired.”

Film/TV

Reservation Dogs (FX on Hulu) via @RezDogsFXonHulu

“Filmed on location in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, #ReservationDogs is a breakthrough in Indigenous representation on television both in front of and behind the camera. Every writer, director and series regular on the show is Indigenous.”

Trailer:

Twitter List:

Lectures

The Vanishing Indian Speaks Back: Race, Genomics, and Indigenous Rights via @MSFTresearch with @kimtallbear

“Speaker: Dr. Kim TallBear, Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Peoples, Technoscience and Environment., Faculty of Native Studies, University of Alberta

Central to US history is the idea that Indigenous peoples were destined to vanish. It is a cherished national myth that the “red” race simply faded away, leaving empty land for inevitable occupation and development by white civilization. The classic image of “the Vanishing American” illustrates this myth; it graced early twentieth-century novels and movie posters, including a film by the same name. In that image, a stereotypical, nineteenth-century plains “Indian” sits on horseback, facing west into the sun that sets on his epoch. The Indian’s otherwise copper-colored body fades to white or disappears; these are the same outcome. After the Indian wars, white society assumed the Indian would finally die out and politicians tried to hurry things along. The US government mandated assimilation through education, child adoption, employment, and urban relocation programs designed to “kill the Indian and save the man.” US policy also defined the Indian out of existence by implementing the racial idea of diminishing “Indian blood quantum.” Such ideas continue to shape American thought, including the genome sciences.

Join University of Alberta Indigenous Science and Technology Studies scholar, Kim TallBear (Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate), as she examines: 1) how older notions of race continue to influence genome scientists who study Indigenous populations today; and 2) the cultural politics involved in the marketing since the early 2000s of “Native American DNA” tests to an American public searching to appropriate Indigenous “identity.””

—

Indigenous Peoples and Technoscience

“NS 115 introduces students to the intricate connections between science and technology fields, broader dynamics of colonialism, and increasing demands for Indigenous governance of science and technology. The course is structured by centering Indigenous peoples’ relationships to science and technology fields as “objects/subjects,” “collaborators,” and “scientists.”

Paper

A global assessment of Indigenous community engagement in climate research

“Abstract: For millennia Indigenous communities worldwide have maintained diverse knowledge systems informed through careful observation of dynamics of environmental changes. Although Indigenous communities and their knowledge systems are recognized as critical resources for understanding and adapting to climate change, no comprehensive, evidence-based analysis has been conducted into how environmental studies engage Indigenous communities. Here we provide the first global systematic review of levels of Indigenous community participation and decision-making in all stages of the research process (initiation, design, implementation, analysis, dissemination) in climate field studies that access Indigenous knowledge. We develop indicators for assessing responsible community engagement in research practice and identify patterns in levels of Indigenous community engagement. We find that the vast majority of climate studies (87%) practice an extractive model in which outside researchers use Indigenous knowledge systems with minimal participation or decision-making authority from communities who hold them. Few studies report on outputs that directly serve Indigenous communities, ethical guidelines for research practice, or providing Indigenous community access to findings. Further, studies initiated with (in mutual agreement between outside researchers and Indigenous communities) and by Indigenous community members report significantly more indicators for responsible community engagement when accessing Indigenous knowledges than studies initiated by outside researchers alone. This global assessment provides an evidence base to inform our understanding of broader social impacts related to research design and concludes with a series of guiding questions and methods to support responsible research practice with Indigenous and local communities.”

—

Too late for indigenous climate justice: Ecological and relational tipping points

“It may be too late to achieve environmental justice for some indigenous peoples,

and other groups, in terms of avoiding dangerous climate change. People in the

indigenous climate justice movement agree resolutely on the urgency of action to

stop dangerous climate change. However, the qualities of relationships connecting

indigenous peoples with other societies' governments, nongovernmental organiza-

tions, and corporations are not conducive to coordinated action that would avoid

further injustice against indigenous peoples in the process of responding to climate

change. The required qualities include, among others, consent, trust, accountability,

and reciprocity. Indigenous traditions of climate change view the very topic of cli-

mate change as connected to these qualities, which are sometimes referred to as kin

relationships. The entwinement of colonialism, capitalism, and industrialization

failed to affirm or establish these qualities or kinship relationships across societies.

While qualities like consent or reciprocity may be critical for taking coordinated

action urgently and justly, they require a long time to establish or repair. A rela-

tional tipping point, in a certain respect, has already been crossed, before the eco-

logical tipping point. The time it takes to address the passage of this relational

tipping point may be too slow to generate the coordinated action to halt certain

dangers related to climate change. While no possibilities for better futures should

be left unconsidered, it's critical to center environmental justice in any analysis of

whether it's too late to stop dangerous climate change.”

—

Ensuring climate services serve society: examining tribes’ collaborations with climate scientists using a capability approach

“Interest in climate service efforts continues to grow. However, more critical analysis could enhance how well climate services align with the needs of society. Collaborations between Native American Tribes (Tribes) and Climate Science Organizations (CSOs) providing decision-support for climate change planning accentuate the potential for climate services to have social justice implications through either deepening or softening existing inequities. This paper compares 30 Tribe-affiliated and 36 CSO-affiliated individuals’ perceptions about potential harms and benefits associated with their collaborations with one another. The importance of the potential benefits of collaborations listed outweighed the potential harms listed for both groups, but while climate science organizations rated the potential benefits listed slightly higher than Tribes did, the potential harms listed were much more salient for Tribes. This finding highlights concerns that, without proper training and management, these collaborations may reinforce unequal relationships between settler and Indigenous populations. While CSOs appeared cognizant of their Tribe-affiliated colleagues’ concerns, transitioning from a focus on building trust to establishing and sustaining shared systems of responsibilities might help these collaborations meet the needs of both groups more effectively.”

—

INDIGENOUS COSMOPOLITICS IN THE ANDES: Conceptual Reflections beyond “Politics”

“In Latin America indigenous politics has been branded as “ethnic politics.” Its activism is interpreted as a quest to make cultural rights prevail. Yet, what if “culture” is insufficient, even an inadequate notion, to think the challenge that indigenous politics represents? Drawing inspiration from recent political events in Peru—and to a lesser extent in Ecuador and Bolivia—where the indigenous–popular movement has conjured sentient entities (mountains, water, and soil—what we call “nature”) into the public political arena, the argument in this essay is threefold. First, indigeneity, as a historical formation, exceeds the notion of politics as usual, that is, an arena populated by rational human beings disputing the power to represent others vis-à-vis the state. Second, indigeneity's current political emergence—in oppositional antimining movements in Peru and Ecuador, but also in celebratory events in Bolivia—challenges the separation of nature and culture that underpins the prevalent notion of politics and its according social contract. Third, beyond “ethnic politics” current indigenous movements, propose a different political practice, plural not because of its enactment by bodies marked by gender, race, ethnicity or sexuality (as multiculturalism would have it), but because they conjure nonhumans as actors in the political arena.”

Interactive bibliography: https://relata.mit.edu/work/doi:10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01061.x/

—

Indigenous knowledge and the shackles of wilderness

“The environmental crises currently gripping the Earth have been codified in a new proposed geological epoch: the Anthropocene. This epoch, according to the Anthropocene Working Group, began in the mid- 20th century and reflects the “great acceleration” that began with industrialization in Europe [J. Zalasiewicz et al., Anthropocene 19, 55–60 (2017)]. Ironically, European ideals of protecting a pristine “wilderness,” free from the damaging role of humans, is still often heralded as the antidote to this human-induced crisis [J. E. M. Watson et al., Nature, 563, 27–30 (2018)]. Despite decades of critical engagement by Indigenous and non-Indigenous observers, large international nongovernmental organizations, philan-thropists, global institutions, and nation-states continue to uphold the notion of pristine landscapes as wilderness in conservation ideals and practices. In doing so, dominant global conservation policy and public perceptions still fail to recognize that Indigenous and local peoples have long valued, used, and shaped “high-value ”biodiverse landscapes. Moreover, the exclusion of people from many of these places under the guise of wilderness protection has degraded their ecological condition and is hastening the demise of a number of highly valued systems. Rather than denying Indigenous and local peoples’ agency, access rights, and knowledge in conserving their territories, we draw upon a series of case studies to argue that wilderness is an inappropriate and dehumanizing construct, and that Indigenous and community conservation areas must be legally recognized and supported to enable socially just, empowering, and sustainable conservation across scale.”

Additional:

Indigenous Lessons about Sustainability Are Not Just for “All Humanity”: https://kylewhyte.marcom.cal.msu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2018/07/IndigenousInsightsintoSustainabilityarenotforAllHumanity.pdf

Indigenous Climate Change Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene: https://kylewhyte.marcom.cal.msu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2018/07/IndigenousClimateChangeStudies.pdf

Podcasts

Episode Seventeen: What if indigenous wisdom could save the world? via @robintransition with @sacred411

“Of all the 17 episodes of this podcast so far, this is the one that I had to go off somewhere quiet afterwards for a while to digest. It is a very powerful and fascinating discussion. My two guests are extraordinary, and I feel so blessed that they could make the time to join me in this wonderful What If exploration.

Sherri Mitchell (Weh’na Ha’mu’ Kwasset (She Who Brings the Light)) is an attorney, an activist, an advisor, a speaker and so so so much more, including author of ‘Sacred Instructions: indigenous wisdom for living spirit-based change’. She was born and raised on the Penobscot Indian Reservation.

Tyson Yunkaporta is an academic, an arts critic, and a researcher who belongs to the Apalech Clan in far north Queensland. He carves traditional tools and weapons and also works as a senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges at Deakin University in Melbourne. His recent book, Sand Talk: how indigenous thinking can save the world, is deeply wonderful and I am very much enjoying it right now.

Our discussion focused around the question ‘what if indigenous wisdom could save the world?’, and I hope it blows your mind as much as it did mine. I would recommend taking some time after you’ve listened to it to go for a walk and digest it. It worked for me.”

—

Patterns of Creation with Dr. Tyson Yunkaporta | Talk of Today Podcast via @SamHBarton

“Dr. Tyson Yunkaporta is an Indigenous Australian academic and author of the book 'Sand Talk', which explores our global systems from an Aboriginal perspective and how this viewpoint could help us resolve some of the complex sustainability issues facing our world.

In our conversation we cover:

- The indigenous notion of story and the problem with the narrative at the heart of Western civilisation

- The value in true diversity, identity, and place

- Violence and the need for its integration in society

- Why instead of pursuing growth we should seek 'increase', which I take to be the expansion of the connectedness of things in our world, living and otherwise.

- The need for humanity to retake our place as custodians of the land we're connected to.”

—

The Other Others By Tyson Yunkaporta

“Through the Deakin University Indigenous Knowledge Systems Lab, we have unlikely, borderline seditious and kind of inappropriate yarns with surprising people about how an Indigenous complexity science lens can be applied to solving the world's most wicked problems. There's gold at the margins, but almost no trigger warnings, so enter at your peril. Podcast artwork "Blackfulla Ratatouille" by Baradha woman Eden Thomas. Intro music by The Murri Ghibli Fangirls.”

—

Give The Land Back? via @flashforwardpod

Today we travel to a future where the US and Canada give stolen land back to tribes & bands.

Guests:

Molly Swain — co-host of Métis in Space, studying in the Faculty of Native Studies at the University of Alberta & co-organizer of 2Land 2Furious.

Chelsea Vowel — co-host of Métis in Space, author of Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis & Inuit Issues in Canada & co-organizer of 2Land 2Furious.

Matthew Fletcher — law professor at Michigan State University

Graham Lee Brewer — associate editor at High Country News

Mike Gouldehawke — writer & activist

The intro scene was written & performed by Molly Swain and Chelsea Vowel, along with Johnnie Jae.

—

Indigenous Climate Knowledges and Data Sovereignty via @kstsosie

“In this episode of Warm Regards, we talk to two Indigenous scientists about traditional ecological knowledges and their relationship with climate and environmental data. In talking with James Rattling Leaf, Sr. and Krystal Tsosie, Jacquelyn and Ramesh discuss how these ideas can challenge Western notions of relationality and ownership, how they have been subject to the long history of extraction and exploitation of Indigenous communities (practices which continue today), but also how Indigenous scientists and activists link sovereignty over data created by and for Indigenous people to larger sovereignty demands.

You can find a transcript of this episode on our Medium page:

ourwarmregards.medium.com/indigenous-c…4fc756b9476e”

TED Talks

Indigenous peoples

“A collection of 35 TED Talks (and more) on the topic of Indigenous peoples.”

Twittersphere

“Where can you find Indigenous philosophy? Not in philosophy journals (except very sporadically). The main venues where I've seen are books, e.g., * Maori philosophy https://bloomsbury.com/us/maori-philosophy-9781350101654 * Native American/First nations https://wiley.com/en-us/American+Indian+Thought%3A+Philosophical+Essays-p-9780631223047 https://msupress.org/9781611863307/indigenizing-philosophy-through-the-land/ 1/”

—

“This #IndigenousPeoplesDay, let’s honor the Indigenous communities leading the movement for climate action and environmental justice, and the vital role Indigenous knowledge plays in climate solutions. Thread”

—

“1/4 In just 2 days we’ll be co-hosting the very first congress, #OurLandOurNature, to discuss how to #DecolonizeConservation, as an alternative to the #IUCNcongress.”

—

“Sorry but have to say it: for me wilderness is a settler-colonial concept that erases Indigenous sovereignty.”

—

“Four centuries before Columbus sailed, the world was completely connected for the first time in 18,000 years: Around 1100 AD, European Vikings met Native Americans in Newfoundland, and Native Americans met with Polynesians on Fatu Hiva island (this was just confirmed last year!)”

—

“In honor of Indigenous People’s Day I wanted to provide another thread of films that feature Indigenous Peoples. It’s been so so amazing to see how Indigenous creatives have used and are using film and art to navigate identity and personhood. These are some of my favorite films"

—

“#IndigenousPeoplesDay From 1830 to 1890, 30 million bison were reduced to less than 1,000. They were butchered by the European invaders who were diabolically, hell-bent on inflicting starvation & death upon the native people of North America. photos: Burton Historical Collection”

Videos

Why the IK Systems Lab matters via @deakinresearch

“Paul Kearney, Dr Tyson Yunkaporta and Professor Doug Creighton explore why Deakin University’s IK Systems Lab is a step towards discovering and developing global solutions.”

—

(Video 1) Original Indigenous Economies: Then and Now: via @Policy_ED

“The Hoover Project on Renewing Indigenous Economies conducts research to inform and promote policies that empower Native Americans to regain control over their lives and resources.”

“Native Americans prospered for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. Today they are America’s poorest minority.”

(Video 2) Colonialism: Then and Now

“The stark economic disparities that exist between indigenous peoples and the rest of American society stem directly from policies imposed by the federal government, which has denied secure property rights, clearly defined jurisdictions, and effective governance structures.”

(Video 3) A New Path Forward

To revive their economies, indigenous peoples are restoring the dynamic customs, culture, and dignity that existed before colonization. Visit this project's website here:https://www.policyed.org/renewing-ind...”

“Additional resources:

Read "The Bonds of Colonialism,"by Terry Anderson via Defining Ideas. Available here:https://www.hoover.org/research/bonds...

Read "Quiet Crisis: Federal Funding and Unmet Needs in Indian Country," a 2016 update from Terry Anderson. Available here:https://indigenousecon.org/media/2018...

Watch "Why Indian Nations Fail," a talk by James Robinson at the Hoover Institution. Available here:https://www.hoover.org/events/renewin...

Visit https://indigenousecon.org/ to learn more.”

Websites

Indigenous STS via @indigenous_sts

“Our Mission: Indigenous Science, Technology, and Society (Indigenous STS) is an international research and teaching hub, housed at the University of Alberta, for the bourgeoning sub-field of Indigenous STS. Our mission is two-fold: 1) To build Indigenous scientific literacy by training graduate students, postdoctoral, and community fellows to grapple expertly with techno-scientific projects and topics that affect their territories, peoples, economies, and institutions; and 2) To produce research and public intellectual outputs with the goal to inform national, global, and Indigenous thought and policymaking related to science and technology. Indigenous STS is committed to building and supporting techno-scientific projects and ways of thinking that promote Indigenous self-determination.”

—

Indigenous Knowledge Institute via @IKI_unimelb

“The Indigenous Knowledge Institute aims to advance research and education in Indigenous knowledge systems.

Following a commitment made by Vice-Chancellor Duncan Maskell at the Garma Festival in August 2019, the institute was launched at the 19th Symposium on Indigenous Music and Dance on 3 December 2020, led by the Research Unit for Indigenous Arts and Cultures at the Wilin Centre for Indigenous Arts and Cultural Development.

The Indigenous Knowledge Institute is one of five current Melbourne Interdisciplinary Research Institutes. These institutes aim to promote research linkages and collaboration across the University and to play a lead role in articulating University research to external audiences.

The Indigenous Knowledge Institute will build on the research and education activities already underway at the University to become a global leader in Indigenous knowledge research and education. The Institute will also build on the work of the Indigenous Hallmark Research Initiative which ceased operation in 2019.”

—

The Indigenous Knowledges Systems Lab

“Explore the National Indigenous Knowledges Education Research and Innovation Institute

What is NIKERI Institute?

The National Indigenous Knowledges Education Research Innovation (NIKERI) Institute enables Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians the flexibility to access higher education while maintaining their family, work and community commitments.

Our courses are highly flexible thanks to our unique Community Based Delivery which is a combination of online teaching and on campus intensives. This allows you to balance your studies with other commitments, regardless of where you live in Australia.

The key difference of choosing to study at NIKERI Institute is that you are part of a culturally safe learning environment, studying in smaller classes alongside other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students.”

—

Yellowhead Institute - @Yellowhead_

“OUR MISSION

Yellowhead Institute generates critical policy perspectives in support of First Nation jurisdiction.

The Institute is a First Nation-led research centre based in the Faculty of Arts at Ryerson University in Toronto, Ontario. Privileging First Nation philosophy and rooted in community networks, Yellowhead is focused on policies related to land and governance. The Institute offers critical and accessible resources for communities in their pursuit of self-determination. It also aims to foster education and dialogue on First Nation governance across fields of study, between the University and the wider community, and among Indigenous peoples and Canadians.

Why Yellowhead?

For too long, the relationship between First Nation peoples and Canadians has been characterized by inertia: the same old, paternalistic and racist policies and the corresponding apathy and neglect. Yet, the resistance of Indigenous peoples continues to grow and today, there is an acceptance on behalf of governments and Canadians that change is required. This is a tremendous opportunity. The challenge is ensuring the direction of change is towards the transformational. Yellowhead Institute can play an important role here, scrutinizing government policy, advocating for the rights of First Nation peoples, and models of change that support First Nation jurisdiction.

Outside of First Nation political organizations, activists, or academics, there is no national entity bringing an evidence-based, non-partisan, and community-first perspectives to the discussions. This is a glaring absence in First Nations ability to organize and mobilize to protect their rights and jurisdiction. The Yellowhead Institute aims to address this gap.

Five Core Objectives

01. Shaping new governance models and supporting governance work in First Nations communities and urban communities

02. Influencing policy development and holding governments accountable for policies affecting First Nations

03. Contributing to public education on the legal and political relationship between First Nations and Canada

04. Facilitating opportunities for, and supporting Indigenous students and researchers

05. Building solidarity with non-Indigenous students and researchers”

—

The Red Nation via @The_Red_Nation

“The Red Nation is dedicated to the liberation of Native peoples from capitalism and colonialism. We center Native political agendas and struggles through direct action, advocacy, mobilization, and education.”

More on Eclectic Spacewalk:

Subscribe to Substack Newsletter

Listen to all podcasts on Anchor

Follow Eclectic Spacewalk on Twitter