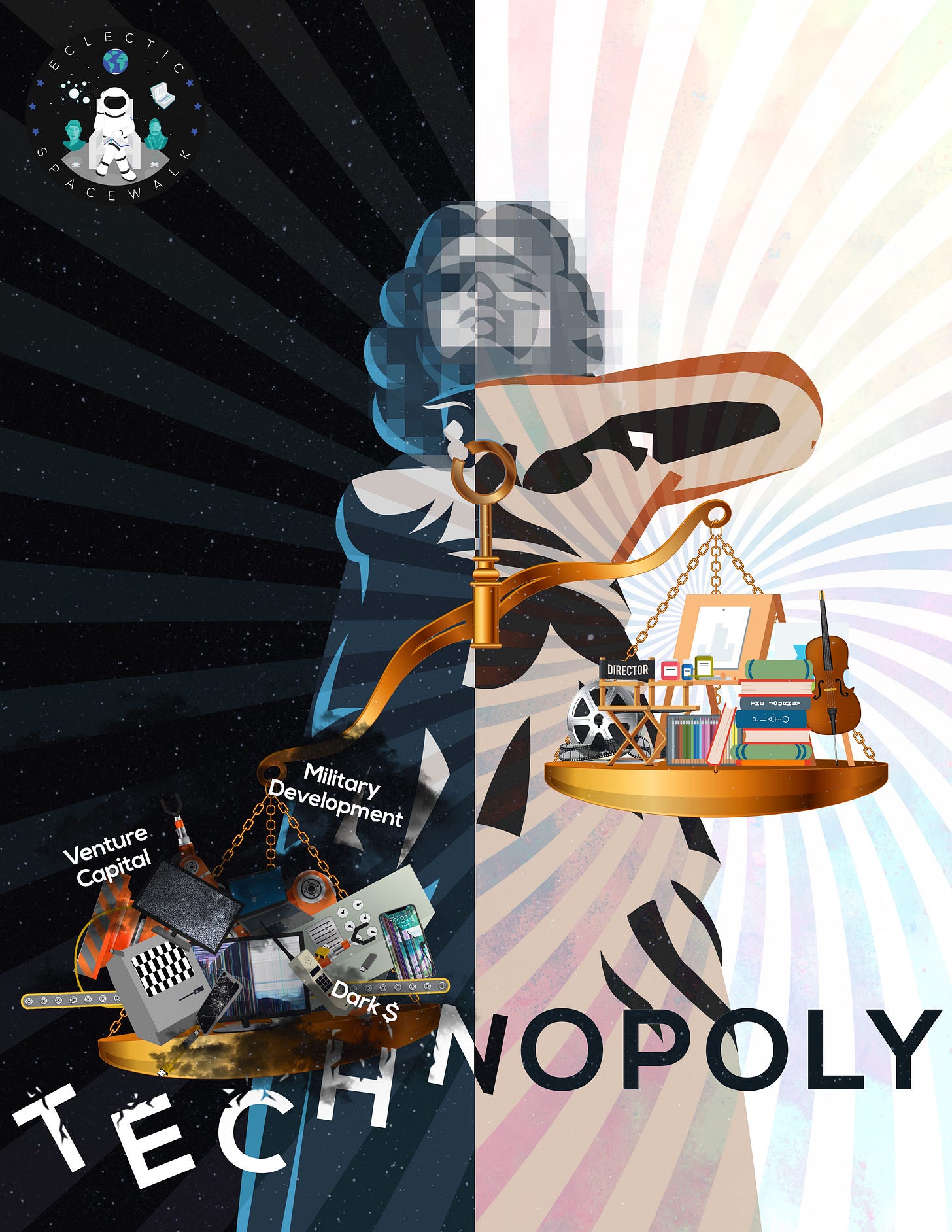

Eclectic Spacewalk #13 - Technopoly

The surrender of culture to technology and what to do about it

Read previous post: Open Source Everything

Watch #ESconversations on YouTube or Listen on Anchor, Spotify, & more

Table of Contents:

Act 1: The Judgement of Thamus

Every invention is BOTH a burden AND a blessing

We should be critical of ALL technologies

Technophiles “one-eyed prophets” vs. Technophobes “one-eyed prophets’ and becoming a “Critical User of Technology”

Act II: Tools → Technocracy → Technopoly

Tools & Kranzberg’s 6 laws of technology

Technocracy & two opposing worldviews

Technopoly’s supremacy starting with Henry Ford & the USA

Act III: So what then?

Being a Loving Resistance Fighter

7 questions we must ask about any new technology

After Technopoly & Mythmaking

Act IV: Mythmaking into Cosmotechnics

Standard Critique of Technology

Yuk Hui’s novel Thesis/Antithesis approach

Cosmotechnics

Text (1 book)

Audio (8 episodes)

Video (6 videos)

Presentations (2 presentations)

Reading Time: 25-30 minutes (Read the sections you find intriguing, bookmark the media/links, and come back to anytime.)

Technopoly—

Abstract: “The surrender of our culture, social institutions, and ultimately humanity’s lives to technology. Technology’s own wants, dreams, and desires, not its creators, us humans, are made reality. Questioning technology’s design & uses, becoming a loving resistance fighter, and creating a “cosmotechnics' culture towards technology are practical ways we can help blunt Technopoly’s impact force.”

ACT I—The Judgement of Thamus

In Plato’s Phaedrus, there is a formidable lesson that individuals and societies, especially in modern times, should learn when thinking and acting on new technologies. The story is about Thamus, a king of a large city in ancient Egypt, and the god of invention - Theuth.

The tale goes that Theuth, being the god of invention and very fond of his creations, boasted a little too much to Thamus about how great of an invention writing was. Specifically, how writing would increase memory and thus wisdom. Thamus, being a wise king himself, replied, “Theuth, my paragon of inventors, the discoverer of an art is not the best judge of the good or harm which will accrue to those who practice it.”

For the quote to really resonate, take a moment and consider the person who invented the clock. Ponder how illogical, irrational, and downright erratic the system framework sounds when explained plainly:

Inventor: there will be 12 numbers on it

Friend: so the day will be divided into 12 segments?

Inventor: no, 24

Friend: so will the day start at 1?

Inventor: the day will start at the 12, which is at night

Friend:

Inventor: the 6 means 30

To drive the point even further, here is a quite humorous TikTok:

Getting back to the story, although King Thamus is correct in his pronouncement about the inventor and their inventions, he proves that even a wise king has flaws in his thinking. He oversteps in boasting that writing will only be used to create false wisdom. Theuth believes that writing will ABSOLUTELY create wisdom and Thamus believes the exact same technology, writing, will ONLY create false wisdom. Obviously, it does not take much reasoning or intellect to arrive at the conclusion that they are both wrong in their final thoughts.

The lesson we draw from Thamus’ judgment is that technology, any technology, be it in the past, present, or future will NEVER have a one-sided effect. This goes for writing, automobiles, virtual reality, drones, social media, and all the like. Individuals and societies must take a critical approach to discussing and implementing policy & design within our technological and social landscape.

Neil Postman in his prescient book, Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology, describes technological change as “neither additive nor subtractive. It is ecological. I mean ‘ecological’ in the same sense as the word is used by environmental scientists. One significant change generates total change.” Postman is describing the brutally honest truth that new technologies, and their effects, don’t limit themselves just to human activity or one sphere of influence. They are all-encompassing and directly visible in some regards, but also invisible and ever-present in others.

A parallel example is in the ecology of media. When a new technology is introduced, it does not add or subtract anything from the whole. It, quite literally, changes everything. Postman, as any critical thinker would, begins to riff on the implications of such paradigm shifts and asking the important who, what, when, where, and why questions:

“What we need to consider about the computer has nothing to do with its efficiency as a teaching tool. We need to know in what way it is altering our conception of learning, and how, in conjunction with television, it undermines the old idea of school.”

“Who cares how many boxes of cereal can be sold via television? We need to know if television changes our conception of reality, the relationship of the rich to the poor, the idea of happiness itself.”

“A preacher who confines himself to considering how a medium can increase his audience will miss the significant question: In what sense do new media alter what is meant by religion, by church, even by God?”

“And if the politician cannot think beyond the next election, then we must wonder about what new media do to the idea of political organization and to the conception of citizenship.”

Postman also describes how different cultures will have different approaches to any new technology. Oral cultures usually elevate togetherness, group learning, and cooperation, as print cultures put competition, personal autonomy, and the individual as the most important. Oral cultures are highly contextualized, as they are grounded in place, while print cultures are primarily low context and field-independent or use ‘universals’. Theuth being favored by print cultures, and Thamus being the champion of oral cultures.

“On the one hand, there is the world of the printed word with its emphasis on logic, sequence, history, exposition, objectivity, detachment, and discipline. On the other, there is the world of television with its emphasis on imagery, narrative, presentness, simultaneity, intimacy, immediate gratification, and quick emotional response,” explains Postman.

Recent studies in visual art tend to agree with Postman’s, and others, hypothesis “our results suggest that, on the one hand, the way that artists represent the world in their paintings influences the way that culturally embedded viewers perceive and appreciate paintings, but on the other hand, independent of the cultural background, anthropological universals are disclosed by the preference of landscapes.”

No one wants to be what Postman describes as a ‘technophile’ - a person who is oblivious to all the wrongs of technology and elevates it to a religious experience; but also no one wants to be described as a ‘technophobe’ - a person who is convinced that technology is some sort of plague on humanity and anything that comes from it is on par with evil. Postman describes both the techophile and technophobe as ‘one-eyed prophets.’ Theuth and Thamus are both one-eyed prophets because their own biases are preventing them from seeing the whole picture.

Postman says that this is in large part due to culture differences, “Our understanding of what is real is different...embedded in every tool is an ideological bias, a predisposition to construct the world as one thing rather than another, to value one thing over another, to amplify one sense or skill or attitude more loudly than another.”

In other words, ‘The medium is the message’ as Marshall McLuhan famously said.

Harold Innis, a Canadian political theorist, had such a profound effect that McLuhan wrote the new introduction to Innis’s most famous work The Bias of Communication saying, “Most writers are occupied in providing accounts of the content of philosophy, science, libraries, empires, and religions. Innis invites us instead to consider the formalities of power exerted by these structures in their mutual interaction. He approaches each of these forms of organized power as exercising a particular kind of force upon each of the other components in the complex.”

The development of communication media is what Innis says is the key to social change. To begin any inquiry, he suggests three basic questions to ask:

How do specific communication technologies operate?

What assumptions do they take from and contribute to society?

What forms of power do they encourage?

If we think of new technology as ecological we can begin to see them for what they are with ‘both eyes open.’ Only when we acknowledge technology’s successes, while also being transparent about its failings, can we understand what a new technology is designed to do through the formula: Form→Function. The uses of any technology are almost always determined by the structure, or topology, of the technology itself. Its functions follow its form(s).

Words, meanings, and terms change when a new technology bursts onto the scene. It sometimes can even have an opposite meaning of what the previous meaning was. Just think about the word “connection,” and how it has changed over the course of the digital revolution. Connection was defined very differently before the Internet and will continue to change as our digital sphere enlarges.

Technology has and will continue to redefine words like: “freedom,” “truth,” “intelligence,” “fact,” “wisdom,” “memory,” and “history.” Postman goes further than just language and says, “New technologies alter the structure of our interests: the things we think about. They alter the character of our symbols: the things we think with. And they alter the nature of community: the arena in which thoughts develop.”

Act II: Tools → Technocracy → Technopoly

Tools

The history of Homo Sapiens is one of sophisticated tool use. There is evidence that our ancestors, Homo Habilis and Homo Erectus, invented tools and language respectively. Which allowed us, humans, to organize, multiply, and spread across the globe. For millennia, and up until a few centuries ago, the pinnacle of human ingenuity was utilizing & manipulating the surrounding environment with tools.

At first, tool use was as simple and direct as sharpening rocks for the cutting of wood and animal hides, as well as combat with other humans. Then, tool usage increased after more and more humans banded together in groups and deployed some of those insights from individuals for the benefit of others. And then, it was the continued evolution of better and more useful tools amongst larger groups of ancient humans that birthed what we now call civilization. Larger and larger bands of humans came together for celestial celebrations or seasonal exchange of goods, sometimes under the influence of psychedelics. They stayed in one place more and more often, rather than continuing to travel in roving parties across the land, which cemented tools as integral to human prosperity over our history after countless iterations from both.

“We have become the tool of our tools.” ― Henry David Thoreau

Thamus, Thoreau, McLuhan, Innis, and Postman all realized that “technologies create the ways in which people perceive reality, and that such ways are the key to understanding diverse forms of social and mental life.” It follows that to speak about technological changes with any credibility or authority, we must again realize that different cultural setups will garner different technological outcomes even with the exact same technology. Karl Marx had a perfect aphorism for this unique dynamic, “the hand-loom gives you society with a feudal lord; the steam-mill, society with the industrial capitalist.”

In the mid-1980s, Dr. Melvin Kranzberg, a professor of the history of technology at the Georgia Institute of Technology unveiled his 6 Laws of Technology for the first time at the Society for the History of Technology’s annual meeting. The Kranzberg 6 Laws of Technology are detailed below in L. M. Sacasas’s blog, and now EBook, ‘The Frailest Thing’:

“First Law: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.” By which he means that,

“technology’s interaction with the social ecology is such that technical developments frequently have environmental, social, and human consequences that go far beyond the immediate purposes of the technical devices and practices themselves, and the same technology can have quite different results when introduced into different contexts or under different circumstances.”

Here are the remaining laws with brief explanatory notes:

Second Law: Invention is the mother of necessity. “Every technical innovation seems to require additional technical advances in order to make it fully effective.”

Third Law: Technology comes in packages, big and small. “The fact is that today’s complex mechanisms usually involve several processes and components.”

Fourth Law: Although technology might be a prime element in many public issues, nontechnical factors take precedence in technology-policy decisions. “… many complicated sociocultural factors, especially human elements, are involved, even in what might seem to be ‘purely technical’ decisions.” “Technologically ‘sweet’ solutions do not always triumph over political and social forces.”

Fifth Law: All history is relevant, but the history of technology is the most relevant. “Although historians might write loftily of the importance of historical understanding by civilized people and citizens, many of today’s students simply do not see the relevance of history to the present or to their future. I suggest that this is because most history, as it is currently taught, ignores the technological element.”

Sixth Law: Technology is a very human activity-and so is the history of technology. “Behind every machine, I see a face–indeed, many faces: the engineer, the worker, the businessman or businesswoman, and, sometimes, the general and admiral. Furthermore, the function of the technology is its use by human beings–and sometimes, alas, its abuse and misuse.”

All of Kranzberg’s laws are valuable to any critical user of technology, but if each and every person can start with the First Law: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral,” enough questions will ensue for any curious mind that will be formative to see technology with both eyes wide open.

Postman divided up human culture into three distinct types: Tool using, Technocracy, and Technopoly. Until the 17th century, we could classify ALL cultures as being tool using. Tools back then were usually in the form of problem-solving mechanisms for use in physical life (waterwheels, windmills, etc), or to serve as an homage to literal higher powers, like cathedrals, and the connection between humans and the divine, like mechanical clocks. Politics, art, religion, rituals, and even symbolism were not attacked by these tools per se but usually were directed and used as controlling forces to the specific uses of a technology.

Tools were usually never given the moniker of “autonomous” and always had the cultural imprint of the times they were made in, but we also have to realize that the people up until a few hundred years ago were surprisingly sophisticated somewhat because of their shared cultural beliefs. Postman goes further, “all tool-using cultures--from the technologically most primitive to the most sophisticated--are theocratic, or if not, unified by some metaphysical theory.”

Technocracy

Some tool-using cultures officially transitioned to the first technocracies in the late 17th century with the death of Galileo, the birth of Isaac Newton, and the official recognition of Copernicus and Kepler's life’s work showing that the Earth is indeed not the center of the universe. “That moral center had allowed people to believe that the earth was the stable center of the universe and therefore that humankind was of special interest to God. After Copernicus, Kepler, and especially Galileo, the Earth became a lonely wanderer in an obscure galaxy in some hidden corner of the universe, and this left the Western world to wonder if God had any interest in us at all,” says Postman.

“In the ensuing explosion, Aristotle’s animism was destroyed, along with almost everything else in his Physics. Scripture lost much of its authority. Theology, once the Queen of the Sciences, was now reduced to the status of Court Jester. Worst of all, the meaning of existence itself became an open question,” exclaims Postman. There was a clear edict for the separation of moral and intellectual values. This rocked the premodern world to its core.

Tools are revered for their influence on culture, even their seamless integration into them. Postman says that was probably true in the tool using cultures but when we live in a Technocracy the tools are much more pernicious and attack culture, “They bid to become the culture. As a consequence, tradition, social mores, myth, politics, ritual, and religion have to fight for their lives.”

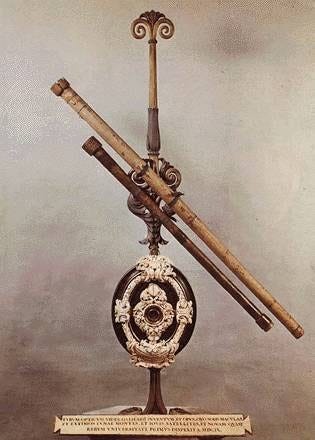

“The modern technocracies of the West have their roots in the medieval European world, from which there emerged three great inventions: the mechanical clock, which provided a new conception of time; the printing press with movable type, which attacked the epistemology of the oral tradition; and the telescope, which attacked the fundamental propositions of Judeo-Christian theology. Each of these are significant in creating a new relationship between tools and culture,” concludes Postman.

“The greatest invention of the 19th century was the invention of the method of invention.” - Alfred North Whitehead

“The idea that if something could be done it should be done was born in the nineteenth century...We had learned how to invent things, and the question of why we invent things receded into importance,” laments Postman. This type of society is also self-perpetuating, “In a technocracy--that is, a society only loosely controlled by social custom and religious tradition and driven by the impulse to invent--an “unseen hand” will eliminate the incompetent and reward those who produce cheaply and well the good that people want.”

Technocracies were officially off to the races! The seemingly unlimited supply of progress that we see around us now, in today’s future world, was born in technocracy’s beginnings. Tradition be damned even though it was still ever-present and the only universal societal framework that these technologies could graf themselves on to before they burst out with the promise of new freedoms. Postman says there was no time to look back or contemplate what was being lost as “Technocracy also sped up the world. We could get places faster, do things faster, accomplish more in a shorter time. Time, in fact, became an adversary over which technology could triumph.”

Postman goes on by summarizing that two distinct thought worlds were trading paint in the race to see who molds the future of society, “And so two opposing world-views--the technological and the traditional--coexisted in uneasy tension. The technological was the stronger, of course, but the traditional was there--still functional, still exerting influence, still too much alive to ignore.”

—

Technopoly

Aldous Huxley’s transformative and groundbreaking book Brave New World introduced the world to a different type of dystopian society. One in which, agency and free will are in question with the drug: soma. Postman says another lesson to be learned from Huxley is how society is taken over by the totality of technological change, “Technopoly eliminates alternatives to itself. It does not make them illegal. It does not make them immoral. It doesn’t even make them unpopular. It makes them invisible and therefore irrelevant. And it does so by redefining what we mean by religion, by art, by family, by politics, by history, by truth, by privacy, by intelligence, so that our definitions fit its new requirements. Technopoly, in other words, is totalitarian technocracy.”

Around the turn of the century is when the first technopolies really began forming. The first being Henry Ford’s motor vehicle empire in the United States with its commitment to being the biggest car manufacturer in the world. Its revolutionary use of assembly lines and the principles of scientific management are arguably what catapulted it to stratospheric levels of success.

Most people have heard of Huxley, and Brave New World, but most have probably never heard of Frederick W. Taylor, the originator of scientific management. Unbeknownst to many, Frederick W. Taylor has had more influence in the armed forces, the legal profession, the church, and education industries than any other person you can think of. His publication of “The principles of Scientific Management, in 1911, contains the first explicit and formal outline of the assumptions of the thought-world of Technopoly,” says Postman.

In a technopoly, workers were relieved of any responsibility to think at all and instead technique of any kind can do our thinking for us. “These include the beliefs that the primary, if not the only, goal of human labor and thought is efficiency; that technical calculation is in all respects superior to human judgemental that in fact human judgment can not be trusted, because it is plagued by laxity, ambiguity, and unnecessary complexity; that subjectivity is an obstacle to clear thinking; that what cannot be measured either does not exist or is of no value; and that the affairs of citizens are best guided and conducted by experts,” opines Postman.

“Whether or not it draws on new scientific research, technology is a branch of moral philosophy, not of science.” - Paul Goodman, New Reformation

The sparse information stream that created a schism of scarcity has now been completely upended to the opposite where information is now a fire hose and creates a schism for abundance. How humanity navigates the changes in dealing with information glut will be a monumental test in how our epistemic crisis unfolds.

“The milieu in which Technopoly flourishes is one in which the tie between information and human purpose has been severed, i.e., information appears indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, in enormous volume and at high speeds, and disconnected from theory, meaning, or purpose,” Postman goes on, ”Technocracy does not have as its aim a grand reductionism in which human life must find its meaning in machinery and technique. Technopoly does.”

“Technopoly deprives us of the social, political, historical, metaphysical, logical, or spiritual basis for knowing what is beyond belief,” concludes Postman

Act III: So what then?

L.M. Sacarass in his E-Book The Frailest Thing gives a pithy response to the question, “So what then?”

“I’m presently resisting the temptation to now turn this short post toward some happy resolution, or at least toward some more positive considerations. Doing so would be disingenuous. Mostly, I simply wanted to draw our attention, mine no less than yours, toward the possibly unpleasant work of counting the costs. As we thought about the new year looming before us and contemplated how we might live it better than the last, I wanted us to entertain the possibility that what will be required of us to do so might be nothing less than a fundamental reordering of our lives. At the very least, I wanted to impress upon myself the importance of finding the space to think at length and the courage to act.”

Do you have the courage to act with the information in this essay?

Without any deep thought, one could assume that if you live in the US or a “western” country you most likely live in a Technopoly. If you don’t live in one of those places, then we hope this essay is illuminating in how to possibly deal with things sure to be coming your way! Technology, in a technopoly, has changed friendship, religion, politics, and even the way we think about politics, as well as education and learning - but what are the solutions to some of these problems we have discussed?

Postman says critics can have a role to play, “it is well known that there are not always solutions to serious problems but if the critic will give it a little thought perhaps something constructive might come from the effort.”

We agree with Postman wholeheartedly, and a big reason why we write these essays. We can use our skillset of putting together engaging AND informative stories for people to ‘trip over their own truth(s),’ and hopefully, we can trip over some of ours own along the way too. Our most recent essays Updated Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth and Open Source Everything continues in that vein, and specifically can be used to orient our thought process and actions towards technological development.

Postman says subjects being taught first as “histories of'' said subject and a re-recognition of the power of semantics, rhetoric, and uses of language would be powerful mechanisms that could alter technopoly’s trajectory over the long term. For the less patient among us, Postman says there inevitably will be people who will take up the banner of resistance and become a fighter against Technopoly. Those who resist will be people:

“who pay no attention to a poll unless they know what questions were asked, and why;

who refuse to accept efficiency as the pre-eminent goal of human relations;

who have freed themselves from the belief in the magical powers of numbers, do not regard calculation as an adequate substitute for judgement, or precision as a synonym for truth;

who refuse to allow psychology or any “social science” to pre-empt the language and thought of common sense;

who are, at least, suspicious of the idea of progress, and who do not confuse information with understanding;

who do not regard the aged as irrelevant;

who take seriously the meaning of family loyalty and honor, and who, when they “reach out and touch someone,” expect that person to be in the same room;

who take great narratives of religion seriously and who do not believe that science is the only system of thought capable of producing truth;

who know the difference between the sacred and the profane, and who do not wink at tradition for modernity’s sake;

who admire technological ingenuity but do not think it represents the highest possible form of human achievement.”

Each person must decide how to enact these ideas for their own sake, and as part of society, says Postman, “In short, a technological resistance fighter maintains an epistemological and psychic distance from any technology, so that it always appears somewhat strange, never inevitable, never natural.”

Postman continues, “A resistance fighter understand that technology must never be accepted as part of the natural order of things, that every technology -- from an IQ test to an automobile to a television set to a computer -- is a product of a particular economic and political context and carries with it a program, an agenda, and a philosophy that may or may not be life-enhancing and that therefore require scrutiny, criticism, and control.”

To be a Loving Resistance Fighter and a critical user of technology with “both eyes open” one would exude the above criteria, but also asks the following seven questions regarding any new technology:

What is the problem to which this technology is the solution?

Whose problem is it?

What new problems will be created when solving an old problem?

Which people and which institutions will be most harmed?

What changes in language are being enforced/promoted by new technologies? What is being gained? And lost from such changes?

What shifts in economic & political power are likely to result?

What alternative uses (Media/mediums, etc) might be made of a technology? (Assuming that any medium we have created is not necessarily the only one we make of a particular technology.)

- L.M. Sacasas expanded the list to 41 questions concerning technology

Asking these seven questions and being a loving resistance fighter is still not enough though. Technopoly’s supremacy over thought, being, psyche, social institutions, and thus all of us will not come down off its pedestal willingly. We are going to have to get more creative and think bigger - much bigger!

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” - Buckminster Fuller

Alan Jacobs, in his 2019 New Atlantis essay, describes how culture, through the eyes of Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski, has two distinct “cores.” Technology according to Kolakowski is something much deeper than common usage, “It describes a stance toward the world in which we view things around us as objects to be manipulated, or as instruments for manipulating our environment and ourselves.”

Jacobs describes Kolakowski’s first core of culture, “besides tools, the technological core of culture includes also the sciences and most philosophy, as those too are governed by instrumental, analytical forms of reasoning by which we seek some measure of control.” And by contrast, the second core of culture, “the mythical core of culture is that aspect of experience that is not subject to manipulation, because it is prior to our instrumental reasoning about our environment.”

Jacobs joins Kolakowski’s mythical and technological cores premise with Postman’s thesis on culture surrendering to technology, “technopoly arises from the technological core of society but produces people who are driven and formed by the mythical core.”

Summarized further, “Technopoly is a system that arises within a society that views moral life as an application of rules but that produces people who practice moral life by habits of affection, not by rules. (Think of Silicon Valley social engineers who have created and capitalizes upon Twitter outrage mobs.)”

Jacobs thinks that we absolutely live in a Technopoly, but there isn’t much we can do about it on the technological side of things. However, his deep-diving into the mythical core of culture that we could affect goes further than Postman and could indeed give us somewhat of a path, however mythical, out of Technopoly’s current grasp.

Jacobs goes on, “No matter how detailed and specific and imaginative the plans of humans may be, the kami of the landscape will gradually turn those plans toward its own character, its own conformation. Something will emerge, and what emerges will never be what was planned. Though it may incorporate some elements of the planning if those run with the grain, as it were, of the environment.”

“Let us applaud those mythmakers who seek their own quiet corner to develop stories, their communities...To find the better path, we need to re-educate ourselves in mythmaking and in the right reception of myth,” concludes Jacobs.

Act IV: Mythmaking into Cosmotechnics

Alans Jacobs, yes the same Alan Jacobs from above, published an even farther-reaching essay From Tech Critique to Ways of Living two years after the first essay, in 2021, that tries to get off the proverbial armchair. Jacobs says that Neil Postman and his Technopoly thesis are pretty much correct and coherent. However, as Jacobs describes, the argument has mostly fallen flat on getting actual results of any change, “the one problem with the Standard Critique of Technology, or SCT, is that it has had no success in reversing, or even slowing the momentum of our society’s move toward Technopoly.”

Jacobs restates the basic argument of the SCT with legendary poise from all the heavy hitters of tech critique, “We live in a technopoly, a society in which powerful technologies come to dominate the people they are supposed to serve, and reshape us in their image. These technologies, therefore, might be called prescriptive (to use Franklin’s term) or manipulatory (to use Illich’s)...Collectively these technologies constitute the device paradigm (Borgmann), which in turn produces a culture of compliance (Franklin).”

Being anti-technology is like being anti-air or anti-food. As we learned from the very beginning of our story, with the god Theuth and Thamus, shunning technology is never the answer to any problem regarding the uses of technology. Jacobs says that our task is therefore to, “find and use technologies that, instead of manipulating us, serve sound human ends and the focal practices (Borgmann) that embody those ends...those healthier technologies might be referred to as holistic (Franklin) or convivial (Illich), because they fit within the human lifeworld and enhance our relations with one another...is to discern these tendencies or affordances of our technologies and, on both social and personal levels, choose the holistic, convivial ones.”

That was the basic argument of the SCT, and the basic response and solution to the argument has not been enough, says Jacobs, “For all its cogency, the SCT is utterly powerless to slow our technosocial momentum, much less to alter its direction.”

Jacobs points to the work of philosopher Yuk Hui, who has suggested: “that we go wrong when we assume that there is one question concerning technology, the question, that is universal in scope and uniform in shape.” This is ultimately a failure of our imagination, and to use a previous term, mythmaking. Hui’s novel approach asks where technology can be seen as universal:

“Thesis: Technology is an anthropological universal, understood as an exteriorization of memory and the liberation of organs, as some anthropologists and philosophers of technology have formulated it.

Antithesis: Technology is not anthropologically universal; it is enabled and constrained by particular cosmologies, which go beyond mere functionality or utility. Therefore, there is no single technology, but rather multiple cosmotechnics.”

Well, we already know from above how the form makes a technology’s function, the medium is the message, etc., so multiple cosmotechnics must be correct. “It is the unification of the cosmos and the moral through technical activities, whether craft-making or art-making. That is, cosmotechnics is the point at which a way of life is realized through making,” says Jacobs.

Hui’s approach puts the progression of traditional → systematic → situational to the ultimate test, “I believe that to overcome modernity without falling back into fascism, it is necessary to reappropriate modern technology through the renewed framework of a cosmotechnics.” Jacobs describes Hui’s project as “doesn’t refuse modern technology, but rather looks into the possibility of different technological futures.”

Looking into different technological futures has usually been the bread and butter for science fiction, but Hui’s approach goes further than imagining, “It is from the ten thousand things that we learn how to live among the ten thousand things; and our choice of tools will be guided by what we have learned from that prior and foundational set of relations. This is cosmotechnics,” exclaims Jacobs.

Localism, and possibly Bioregionalism, will be an effective framework for cosmotechnics says Jacobs, “a cosmotechnics is a living thing, always local in the specifics of its emergence in ways that cannot be specified in advance.” Hui believes that the fundamental concern of Western Philosophy is with being and substance, the fundamental concern of Classical Chinese thought is relation. This harkens back to those visual art studies that show how different people see art differently.

Hui continues, “Thinking rooted in the earthly virtue of place is the motor of cosmotechnics. However, for me, this discourse on locality doesn’t mean a refusal of change and of progress, or any kind of homecoming or return to traditionalism; rather, it aims at a re-appropriation of technology from the perspective of the local and a new understanding of history.”

One of localism’s paragon’s Wendell Berry had only two questions to ask, that eventually turns into one, in regards to change that can guide our local understanding of technology and its uses: “Two questions, then, remain: Is a change for the better possible? And who has the power to make such a change? I still believe that a change for the better is possible, but I confess that my belief is partly hope and partly faith. No one who hopes for improvement should fail to see and respect the signs that we may be approaching some sort of historical waterfall, past which we will not, by changing our minds, be able to change anything else. We know that at any time an ecological or a technological or a political event that we will have allowed may remove from us the power to make change and leave us with the mere necessity to submit to it. Beyond that, the two questions are one: the possibility of change depends upon the existence of people who have the power to change.”

In our Updated Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth we stated the importance of bottom-up leadership rather than a top-down approach, “An updated version of Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth will not be a book, but a collection of 1000s of local cultures and memories. We can begin creating this living database with the construction of an updated framework for the discipline of Anticipatory Design Science education, which is both Macro-comprehension AND micro-incisive. Ranging through the entire inter-related GLOCAL (Global to Local) scale.”

Jacobs makes the distinction between a top-down vs. a bottom-up approach, “What is required, then, is not a cosmopolitanism that unifies and regulates but rather a cosmopolitanism of difference.” Jacobs concludes on a thoughtful and promising note that there is still a chance that humanity could thread the needle in regards to the uses of technology, if only we could find the wise people among us, “A synergy could emerge--if only we can find the sages necessary to make this cosmotechnics compelling.”

Find the other Sages!

TEXT

Technopoly by Neil Postman

“In this witty, often terrifying work of cultural criticism, the author of Amusing Ourselves to Death chronicles our transformation into a Technopoly: a society that no longer merely uses technology as a support system but instead is shaped by it--with radical consequences for the meanings of politics, art, education, intelligence, and truth.”

AUDIO

TSV Episode 21: Media Ecology and the McLuhan Institute w/ Andrew McLuhan

The main difference between Postman and McLuhan was that Postman thinks that you need to observe a moral component when thinking and dealing with Technology

“This episode features Andrew McLuhan. Andrew is the grandson of Marshall McLuhan and the son of Eric McLuhan. Together the McLuhans have written dozens of books on media theory and philosophy and they’ve coined many of the field's key concepts and insights. In 2017 Andrew founded The McLuhan Institute, which stores some of the McLuhans’ books, notes, annotations, papers, artifacts, and more. We talked about the institute and what thinking like a McLuhan can offer us today.”

—

Free Thoughts meets Building Tomorrow with special guests Matthew Feeney & Paul Matzko as we discuss whether or not to fear emerging tech.

“Like economic policy, it can be hard to judge the relative freedom of tech policy. Depending on the tech policy we are referring to, the United States is still a massive hub and innovator. That is not to say that we do not have current regulations that may inhibit innovation of certain emerging tech sectors. Naturally, with new technology, comes fear of the unknown and we have to make sure that we do not succumb to those fears. Listening to fears could result in limiting our ability to develop the tech to the fullest extent.

How do we address the federalism question when it comes to tech policy? When it comes to emerging tech, are we forced to imagine threats? Should we be concerned about the level of pervasive private surveillance? What threat do Amazon, Google, and Facebook pose since they centralize our data?”

—

Neil Postman was a prophet

“Two audio clips from Neil Postman beautifully capture some of the ideas that animate this Towers of Babel project. (Please listen to the AUDIO, above.)

One of the key passages:

… But there are schools that have been animated by a transcendent spiritual idea which may be called a god with small ‘g’. Now I know it’s risky for me to use this word even with a small ‘g’, because the word has an aura of sacredness and is not to be used lightly. And also because it calls to mind a fixed figure or image. But it is the purpose of such figures or images to direct one’s mind to an idea, and more to the point, to a story. Not any kind of story but one that tells of origins and envisions a future; a story that constructs ideals, proscribes rules of conduct, provides a source of authority and gives a sense of continuity and purpose. A god in the sense I’m using the word is the name of a great narrative, one that has sufficient credibility, complexity, and symbolic power so that it’s possible to organize one’s life and one's learning around it. Without such a transcendent narrative, life has no meaning. Without meaning, learning has no purpose. Without purpose, schools become houses of detention, not attention.”

—

EP118 Matt Ridley on How Innovation Works

“Matt Ridley talks to Jim about his latest book, How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes in Freedom. They cover innovation vs invention, improbable order, the value of technological innovation, the importance of the steam engine, innovation as a team sport, the history of vaccination, fossil fuel’s role in the industrial revolution, negative impacts of patents, the light bulb & simultaneous invention, water chlorination, the Haber–Bosch process, the green revolution, GMO’s, innovation opposition, nuclear power, the western innovation famine, Matt’s bet against Elon Musk’s hyperloop technology, and much more.”

—

Philosophize This! - The Frankfurt School - Walter Benjamin

—

#107 Matt Ridley: Infinite Innovation - The Knowledge Project

—

History of Technology - Neil Postman- the age of computers

VIDEO

Marshall McLuhan - Digital Prophecies: The Medium is the Message

“In the 1960s, way before anybody had ever tweeted, Facebook Live-d or sent classified information to WikiLeaks, one man made a series of pronouncements about the changing media landscape. His name was Marshall McLuhan and you’ve probably heard his most quoted line: “The medium is the message”.”

—

Neil Postman on Technopoly (1992) and Collapse of Civil-ization

“Don't let the human soul perverted by technology, our primitive need is still food, clothes and shelter but we are going very far from ourselves which in return is distorting our identity. We all have to pay very heavy price for that in the future. We can't be without identity, before it was God/ Absolute Truth or in philosophy where we seek identity, now we seek it in celebrity(songs, movies), corporates, government, popular culture which is very dangerous and completely corrupting the culture and distorting the truth.”

—

College Lecture Series - Neil Postman - "The Surrender of Culture to Technology"

“A lecture delivered by Neil Postman on Mar. 11, 1997 in the Arts Center. Based on the author's book of the same title. Neil Postman notes the dependence of Americans on technological advances for their own security. Americans have come to expect technological innovations to solve the larger problems of mankind. Technology itself has become a national "religion" which people take on faith as the solution to their problems. Includes questions from the audience.”

—

#SmartReads | Technopoly by Neil Postman (1992) | #QuoteWorthy Books

—

How Technology Shapes Humans - with Ainissa Ramirez

“Technology shapes us and we shape technology. This has often led to surprises, and unintended consequences throughout history as technology and humans have developed side by side and occasionally things have gone awry.”

—

Hacking Your Mind - PBS

“Follow host, Jacob Ward, (The TODAY Show), from the farthest corners of the globe to the inside of your mind as he sets out to discover we are not who we think we are. We imagine our conscious minds make most decisions but in reality, we go through much of our lives on “autopilot”. And marketers and social media companies rely on it. Hacking Your Mind offers you the autopilot owner’s manual.”

Presentations

Technopoly - https://prezi.com/ohrhzdh8izph/technopoly/

The Judgment of Thamus - Group members: Du Yi Xie Lingen Wu Lin Wang. - https://slideplayer.com/slide/9760350/

What’s Next?

The next newsletter’s subject matter is still being decided on. In the meantime, you can get "The Overview” our weekly roundup of content to scratch your brain’s curiosity-driven itching.

If you enjoyed this post or the work that we do, please share with other potential eclectic spacewalkers, consider subscribing or gift a subscription, or connect with us on social media to continue the conversation! Also, we are advocates of Bitcoin. My address is on my About.Me page if you are feeling extra curious.

Linktree: https://linktr.ee/eclecticspacewalk

Thank You for your time. Until the next post, Ad Astra!