The Overview - May 22, 2020

The Overview is a weekly roundup of eclectic content in-between essay newsletters & "Conversations" podcast episodes to scratch your brain's curiosity itch. This week's theme is "Covid-19 & Community"

Hello Eclectic Spacewalkers,

I wish that you and your family are safe & healthy wherever you are in the world. :)

Here are some eclectic links for the week of May 22nd, 2020.

Enjoy, share, and subscribe!

Table of Contents:

Articles via The Atlantic, The Boston Review, Real Life Mag, Huck Mag, and Dr. Christian Wahl

Book - The Plague by Albert Camus

Discussion - Predicting the Pandemic via Rebel Wisdom

Documentary - The coronavirus pandemic and family life via DW Documentary

E-Book - Essay Collection: There Is No Outside - Covid-19 Dispatches via N+1 & Verso Books (Free to download)

Feature Film - Contagion

Podcast - Dispatches via RadioLab

Short Film - Coronavirus as seen from every country on Earth via Channel 4 News

TED Talk - Coronavirus Is Our Future via Alanna Shaikh at TEDxSMU

Twittersphere - Covid-Projections.com predictions via @Youyanggu

Visualization - A State-by-State Look at Coronavirus in Prisons via The Marshall Project

Website - TestandTrace.com

Articles

Why the Coronavirus Is So Confusing: A guide to making sense of a problem that is now too big for any one person to fully comprehend - via The Atlantic

In the final second of December 31, 1999, clocks ticked into a new millennium, and … not much happened. The infamous Y2K bug, a quirk of computer code that was predicted to cause global chaos, did very little. Twenty years later, Y2K is almost synonymous with overreaction—a funny moment when humanity freaked out over nothing. But it wasn’t nothing. It actually was a serious problem, which never fully materialized because a lot of people worked very hard to prevent it. “There are two lessons one can learn from an averted disaster,” Tufekci says. “One is: That was exaggerated. The other is: That was close.”

Last month, a team at Imperial College London released a model that said the coronavirus pandemic could kill 2.2 million Americans if left unchecked. So it was checked. Governors and mayors closed businesses and schools, banned large gatherings, and issued stay-at-home orders. These social-distancing measures were rolled out erratically and unevenly, but they seem to be working. The death toll is still climbing, but seems unlikely to hit the worst-case 2.2 million ceiling. That was close. Or, as some pundits are already claiming, that was exaggerated.

The coronavirus is not unlike the Y2K bug—a real but invisible risk. When a hurricane or an earthquake hits, the danger is evident, the risk self-explanatory, and the aftermath visible. It is obvious when to take shelter, and when it’s safe to come out. But viruses lie below the threshold of the senses. Neither peril nor safety is clear. Whenever I go outside for a brief (masked) walk, I reel from cognitive dissonance as I wander a world that has been irrevocably altered but that looks much the same. I can still read accounts of people less lucky—those who have lost, and those who have been lost. But I cannot read about the losses that never occurred, because they were averted. Prevention may be better than cure, but it is also less visceral.

The coronavirus not only co-opts our cells, but exploits our cognitive biases. Humans construct stories to wrangle meaning from uncertainty and purpose from chaos. We crave simple narratives, but the pandemic offers none. The facile dichotomy between saving either lives or the economy belies the broad agreement between epidemiologists and economists that the U.S. shouldn’t reopen prematurely. The lionization of health-care workers and grocery-store employees ignores the risks they are being asked to shoulder and the protective equipment they aren’t being given. The rise of small anti-lockdown protests overlooks the fact that most Republicans and Democrats agree that social distancing should continue “for as long as is needed to curb the spread of coronavirus.”…

And the desire to name an antagonist, be it the Chinese Communist Party or Donald Trump, disregards the many aspects of 21st-century life that made the pandemic possible: humanity’s relentless expansion into wild spaces; soaring levels of air travel; chronic underfunding of public health; a just-in-time economy that runs on fragile supply chains; health-care systems that yoke medical care to employment; social networks that rapidly spread misinformation; the devaluation of expertise; the marginalization of the elderly; and centuries of structural racism that impoverished the health of minorities and indigenous groups. It may be easier to believe that the coronavirus was deliberately unleashed than to accept the harsher truth that we built a world that was prone to it, but not ready for it.

In the classic hero’s journey—the archetypal plot structure of myths and movies—the protagonist reluctantly departs from normal life, enters the unknown, endures successive trials, and eventually returns home, having been transformed. If such a character exists in the coronavirus story, it is not an individual, but the entire modern world. The end of its journey and the nature of its final transformation will arise from our collective imagination and action. And they, like so much else about this moment, are still uncertain.”

—

New Pathogen, Old Politics: We should be wary of simplistic uses of history, but we can learn from the logic of social responses - via The Boston Review

“What does all this mean for COVID-19? We face a new virus with uncertain epidemiology that threatens illness, death, and disruption on an enormous scale. Precisely because every commentator sees the pandemic through the lens of his or her preoccupations, it is exactly the right time to think critically, to place the pandemic in context, to pose questions.

The clearest questions are political. What should the public demand of their governments? Through hard-learned experience, AIDS policymakers developed a mantra: “know your epidemic, act on its politics.” The motives for—and consequences of—public health measures have always gone far beyond controlling disease. Political interest trumps science—or, to be more precise, political interest legitimizes some scientific readings and not others. Pandemics are the occasion for political contests, and history suggests that facts and logic are tools for combat, not arbiters of the outcome.

Political interest legitimizes some scientific readings and not others. Pandemics are the occasion for political contests, and history suggests that facts and logic are tools for combat, not arbiters of the outcome.

While public health officials urge the public to suspend normal activities to flatten the curve of viral transmission, political leaders also urge us to suspend our critique so that they can be one step ahead of the outcry when it comes. Rarely in recent history has the bureaucratic, obedience-inducing mode of governance of the “deep state” become so widely esteemed across the political spectrum. It is precisely at such a moment, when scientific rationality is honored, that we need to be most astutely aware of the political uses to which such expertise is put. Looking back to Hamburg in 1892, we can readily discern what was science and what was superstition. We need our critical faculties on high alert to make those distinctions today.

At the same time, COVID-19 has reminded a jaded and distrustful public how much our well-being—indeed our survival—depends upon astonishing advances in medical science and public health over the last 140 years. In an unmatched exercise of international collaboration, scientists are working across borders and setting aside professional rivalries and financial interests in pursuit of treatment and a vaccine. People are also learning to value epidemiologists whose models are proving uncannily prescient.

But epidemiologists don’t know everything. In the end it is mundane, intimate, and unmeasured human activities such as hand-washing and social distancing that can make the difference between an epidemic curve that overwhelms the hospital capacity of an industrialized nation and one that doesn’t. Richards reminds us of the hopeful lesson from Ebola: “It is striking how rapidly communities learnt to think like epidemiologists, and epidemiologists to think like communities.” It is this joint learning—mutual trust between experts and common people—that holds out the best hope for controlling COVID-19. We shouldn’t assume a too simple trade-off between security and liberty, but rather subject the response to vigorous democratic scrutiny and oversight—not just because we believe in justice, transparency and accountability, but also because that demonstrably works for public health.

It is joint learning—mutual trust between experts and common people—that holds out the best hope for controlling COVID-19. We shouldn’t assume a too simple trade-off between security and liberty, but rather subject the response to vigorous democratic scrutiny.

As we do so, it is imperative we attend to the language and metaphors that shape our thinking. Scientists absorb (fundamental) uncertainty within (measurable) risk; public discourse runs along channels carved by more than a century of military models for infectious disease control. By a kind of zoonosis from metaphor to policy, “fighting” coronavirus may in the worst case bring troops onto our streets, security surveillance into our personal lives. Minor acts of corporate charity, trumpeted at a White House bully pulpit, may falsely appear more significant than the solidarities of underpaid, overworked health workers who knowingly run risks every day. Other, democratic, responses are necessary and possible: we need to think and talk them into being.

Perhaps the most difficult paradigm to shift will be to consider infectious agents not as aliens but as part of us—our DNA, microbiomes, and the ecologies that we are transforming in the Anthropocene. Our public discourses fail to appreciate how deeply pathogenic evolution is entangled in our disruption of the planet’s ecosystem. We have known for decades that a single zoonotic infection could easily become pandemic, and that social institutions for epidemic control are essential to provide breathing space for medical science to play catch-up. Our political-economic system failed to create the material incentives and the popular narrative for this kind of global safety net—the same failure that has generated climate crisis.

This is the final, unfinished act of the drama. Can human beings find a way to treat the pathogen not as an aberration, but as a reminder that we are fated to co-exist in an unstable Anthropocene? To expand on the words of Margaret Chan, WHO director at the time of SARS, “The virus writes the rules”—there is no singular set of rules. We have collectively changed the rules of our ecosystems, and pathogens have surprised us with their nimble adaptations to a world that we believed was ours.”

—

The Authoritarian Trade-Off: Exchanging privacy rights for public health is a false compromise - via Real Life Mag

“And here we are in a new global war against another faceless enemy, at least that’s the framing given by many who are directing or influencing the response efforts. “Faced with unforeseen circumstances, a change of mind-set is as necessary in this crisis as it would be in times of war,” says the former president of the European Central Bank in the Financial Times. We “must mobilize accordingly.” Trump, labelling himself a “wartime president,” has leaned fully into this framing. In a recent press briefing, he introduced the “great leaders” of large corporations like Honeywell and Procter & Gamble, who he commended for doing “their patriotic duty” in the fight against the virus. Countries now wage proxy battles against each other through the medium of a health crisis as they fight over medical resources and close off borders in the name of national security — I mean, public health. Many things that are not technically wars are now framed as wars, almost by reflex, whether it’s the war on terror, drugs, or coronavirus. The primary option we are given for understanding crisis of any kind is through protracted mobilization and tragedy.

Many things that are not technically wars are now framed as wars, almost by reflex.

Exploiting crisis is a guiding principle — a best practice for good governance, as the consultant class would put it — for how power is enacted and expanded. The long-term consequences of allowing short-term “solutions” to be applied unabated will mean that, even once the pandemic is alleviated, the crisis will never go away. The programs will be in place and, in the name of prevention, they’ll never be shut off.

The transition to a post-pandemic world isn’t coming at some indeterminate point in the future. It’s already happening, in uneven and variegated ways around the world, in ways that both reflect and distort existing contexts. There’s surveillance authoritarianism in places like China, where technical systems are used to exert more command and control over the vectors of contagion: people. There’s financial authoritarianism in places like the U.S., where politicians call for blood sacrifices to the market and private equity firms plot how to pick the bones of a dead economy. There’s dictatorial authoritarianism in places like Hungary, where prime minister Viktor Orbán has leveraged the pandemic to finally claim unlimited, indefinite power.

As Malcolm Harris noted in this analysis of Covid-19 aid, “In today’s crisis, we’re building tomorrow’s normal.” We can see the steps toward the post-pandemic political order when governments seek “new emergency powers” that echo the powers they claimed after 9/11, like the ability to detain people indefinitely, or access all data deemed relevant, or construct new systems for population management. Or, when major acts of legislation like the $2.2 trillion CARES Act — a corporate bailout with a paltry stimulus check and minimal worker protections attached — is pushed through Congress with a voice vote so there’s no time for debate and no record of decision.

It’s difficult to have foresight now with so much going on. Yet the consequences of more mass surveillance, more social control, more state-corporate power, more mobilizing for war of any kind are so predictable. We need more transparency, more accountability, and, most important, more humanity in how the response is planned and implemented. Otherwise I fear that those who welcome an anything-goes response to today’s crisis will look back in just a few years and wonder whether the crisis can ever end.”

—

The sinister new politics of public space: Your prejudice is showing, Closing parks during a lockdown is inhumane, especially when housing is so cramped and gardens a rare luxury - via Huck Mag

“Public space should be a right for everyone, regardless of their socioeconomic status. Parks should remain open, and we could even go further; opening up golf courses and the gardens of stately homes. Too much land is given over for a tiny number of men to play an elite sport. When we’re all cooped up indoors with little green space to enjoy, it makes perfect sense. The privatisation of public space is a crime, especially when housing is so cramped, and gardens a rare luxury. Don’t close parks, gently ask people to stick to the rules if you have to, but also don’t be one of the people righteously furious at perceived rule-breaking by people you know nothing about. You can’t see sciatica, you can’t see whether a woman sat on a bench with her kids is in a violent relationship that has escalated in brutality with lockdown, and you can’t tell if a group sat together are flatmates. You can tell that people happy to film and denounce complete strangers have a whole raft of prejudices they have used the pandemic to covertly unleash. Keep parks open, use staff to stop dangerous behaviour if necessary, throw open golf courses, and keep your opinions about the general public to yourself.”

—

Panarchy: a scale-linking perspective of systemic transformation - via Dr. Christian Wahl

“This nested hierarchy of systems within systems — or holarchy (Koestler, 1989) of interconnected wholes within wholes — is also referred to as ‘panarchy’ (Gunderson & Holling, 2001). Gunderson and Holling explain that the word ‘panarchy’ describes nature’s (w)holistic hierarchies and the complex dynamics that link different spatial scales and their fast- and slow-moving processes into an interconnected whole.

The panarchy model — interlinked adaptive cycles occurring at multiple temporal and spatial scales simultaneously — elucidates the interplay between change and persistence in scale-linked socio-ecological systems. The model can help us visualize the scale-linking complexity of natural processes.”

Book - The Plague by Albert Camus

“A gripping tale of human unrelieved horror, of survival and resilience, and of the ways in which humankind confronts death, The Plague is at once a masterfully crafted novel, eloquently understated and epic in scope, and a parable of ageless moral resonance, profoundly relevant to our times. In Oran, a coastal town in North Africa, the plague begins as a series of portents, unheeded by the people. It gradually becomes an omnipresent reality, obliterating all traces of the past and driving its victims to almost unearthly extremes of suffering, madness, and compassion.”

Discussion - Predicting the Pandemic via Rebel Wisdom

“The pandemic and the subsequent crisis took our institutions and leaders by surprise. But the people who have been studying complexity and systems for decades saw this coming. What can the lens of systems theory and complexity reveal about the crisis? Rebel Wisdom talks to three experts in the field. Jim Rutt, the former chairman of the world-leading Santa Fe Institute, Nora Bateson, the head of the Bateson Institute and the inventor of 'Warm Data' labs, and Joe Brewer, an expert in complexity research, cognitive science, and cultural evolution.”

Documentary - The coronavirus pandemic and family life | DW Documentary

“The coronavirus crisis is a tough test for families. Many people cannot visit their loved ones for weeks on end, and are looking for opportunities to exchange ideas online or through music. While many parents are pushed to their limits every day working from home without childcare, for others their house in the countryside has become a haven. #mycoronadiary is a co-production between Berlin Producers Media, RBB, DW and Arte.”

Part 1: How Healthcare professionals are coping with coronavirus

Part 2: Being creative in times of the coronavirus pandemic

Part 3: Corona - heroes in crisis mode

Part 4: Coronavirus in closed world in Israel, Iran, Greece

—

Additional Documentaries:

E-Book - Essay Collection: There Is No Outside - Covid-19 Dispatches via N+1 & Verso Books (Free to download)

“A collaboration between the renowned magazine of literature and politics, n+1, and Verso Books, this collection tracks the course of Covid-19 across the circuits of global capital to New York’s prisons and emergency rooms, Los Angeles’s homeless encampments, and the migrant camps in Greece; and into the intimate spaces of our homes, our ideas of how to live, and into our bodies and cells.

We hear from sex workers without work and sailors quarantined on their ships, witness the pandemic from the quiet devastation of upstate New York and quarantined Rome as well as the streets of Delhi, Kashmir, and London and the emergency room of a New York City hospital. From some of the most exciting and thoughtful young writers around the globe, There Is No Outside explores the unspooling wreckage of Covid-19 and helps us on what might come in the aftermath.”

Feature Film - Contagion

“Contagion is a 2011 American thriller film directed by Steven Soderbergh. Its ensemble cast includes Marion Cotillard, Matt Damon, Laurence Fishburne, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow, Kate Winslet, Bryan Cranston, Jennifer Ehle, and Sanaa Lathan. The plot concerns the spread of a virus transmitted by respiratory droplets and fomites, attempts by medical researchers and public health officials to identify and contain the disease, the loss of social order in a pandemic,[2] and the introduction of a vaccine to halt its spread. To follow several interacting plot lines, the film makes use of the multi-narrative "hyperlink cinema" style, popularized in several of Soderbergh's films.” (via Wikipedia)

Podcast - Dispatches via RadioLab

“In a recent Radiolab group huddle, with coronavirus unraveling around us, the team found themselves grappling with all the numbers connected to COVID-19. Our new found 6 foot bubbles of personal space. Three percent mortality rate (or 1, or 2, or 4). 7,000 cases (now, much much more). So in the wake of that meeting, we reflect on the onslaught of numbers - what they reveal, and what they hide.”

“It began with a tweet: “EVERY DAY IS IGNAZ SEMMELWEIS DAY.” Carl Zimmer — tweet author, acclaimed science writer and friend of the show — tells the story of a mysterious, deadly illness that struck 19th century Vienna, and the ill-fated hero who uncovered its cure … and gave us our best weapon (so far) against the current global pandemic.”

“More than a million people have caught Covid-19, and tens of thousands have died. But thousands more have survived and recovered. A week or so ago (aka, what feels like ten years in corona time) producer Molly Webster learned that many of those survivors possess a kind of superpower: antibodies trained to fight the virus. Not only that, they might be able to pass this power on to the people who are sick with corona, and still in the fight. Today we have the story of an experimental treatment that’s popping up all over the country: convalescent plasma transfusion, a century-old procedure that some say may become one of our best weapons against this devastating, new disease.”

“Since the onset of the pandemic, we exist in a constant state of calculation, trying to define our own personal bubble. We’ve all been given a simple rule: maintain six feet of distance between yourself and others. But why six? Producer Sarah Qari uncovers the answer, and talks to some scientists who now say six might not be the right number after all.”

“Covid-19 has put emergency room doctors on the frontlines treating an illness that is still perplexing and unknown. Jad tracks one ER doctor in NYC as the doctor puzzles through clues, doing research of his own, trying desperately to save patients' lives.”

Short Film - Coronavirus as seen from every country on Earth via Channel 4 News

“In an unprecedented global project, Channel 4 News has gathered footage from every country on earth, as filmed during the coronavirus pandemic. It shows the impact of #Coronavirus on every country on earth - from the perspective of those on the ground. From lockdown in London Channel 4 News shows what a pandemic looks like from #AfghanistanToZimbabwe. Only where safe and legal to do so, the people of the world filmed streets, beaches and the cities around them, even if just from their window. A massive thank you to all the contributors around the world, who sent footage. This is what a world under lockdown looks like - from every country.”

TED Talk - Coronavirus Is Our Future | Alanna Shaikh | TEDxSMU

“Global health expert Alanna Shaikh talks about the current status of the 2019 nCov coronavirus outbreak and what this can teach us about the epidemics yet to come. Alanna Shaikh is a global health consultant and executive coach who specializes in individual, organizational and systemic resilience. She holds a bachelor’s degree from Georgetown University and a master’s degree in public health from Boston University. She has lived in seven countries and it the author of What’s Killing Us: A Practical Guide to Understanding Our Biggest Global Health Problems. Recent article publications include an article on global health security in Britain’s Daily Telegraph newspaper and an essay in the Annual Review of Comparative and International Education. She blogs on coaching and personal resilience at www.thisworldneedsbrave.com.”

Twittersphere - Covid-Projections.com predictions via @Youyanggu

“Every Monday for the past 4 weeks, we have been sending our projections to the CDC. So far, http://covid19-projections.com has been the most accurate model every week. In last week's CDC projections, we projected 88,767 deaths on May 16. On May 16, the US reported 88,751 deaths.”

Additional Twittersphere - Coronavirus Tweets THREAD from the Experts via @Noahpinon

Visualization - A State-by-State Look at Coronavirus in Prisons via The Marshall Project

“The Marshall Project is collecting data on COVID-19 infections in state and federal prisons. See how the virus has affected correctional facilities where you live.”

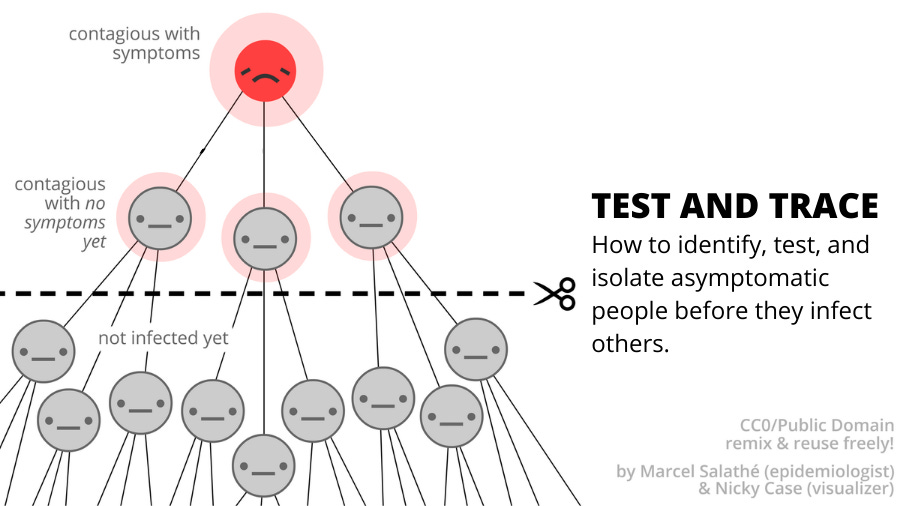

Website - TestandTrace.com

“What is Test and Trace?

Test and Trace is a classic public health approach for containing diseases. It means identifying people who have come into contact with an infected person (contact tracing) , testing them, and then isolating them if they’re sick. This is proven to quickly limit the spread of a deadly disease like COVID-19.

Here’s a basic outline of how Test and Trace works:

1. When someone tests positive for COVID-19, you must find out who they’ve had recent close contact with. This can be done by interviewing them, automatic digital tracing (a recent, modern development), or with public service announcements.

2. Next, notify all of these people (by phone call or text) and have them get tested immediately, even if they don’t have symptoms. They should stay at home until they can get tested.

3. If any of these exposed people test positive, they have to either completely isolate themselves or be isolated at a government facility. This dramatically limits the spread of the virus and asymptomatic transmission.

“If someone is infected, but not yet symptomatic, there’s no way for them to know that they may be contagious…Identifying and isolating presymptomatic individuals is key to limiting transmission.” – Trevor Bedford, epidemiologist at Fred Hutch”

That’s it for this week. Until next time - Ad Astra!

More on Eclectic Spacewalk:

Subscribe to Substack Newsletter

Listen to all podcasts on Anchor

Follow Eclectic Spacewalk on Twitter