The Overview - June 19, 2020

The Overview is a weekly roundup of eclectic content in-between essay newsletters & "Conversations" podcast episodes to scratch your brain's curiosity itch.

Hello Eclectic Spacewalkers,

I wish that you and your family are safe & healthy wherever you are in the world. :)

Check out last week’s essay #11: Updated Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth

—

Here are some eclectic links for the week of June 19th, 2020.

In honor of today being Juneteenth, this week's theme is:

"Anti-Racism"

Enjoy, share, and subscribe!

Table of Contents:

Articles via The Atlantic, CNN, LA Review of Book, LA Time Editorial Board, Boston Review, N+1 Mag, Harvard Business Review

Books - Race Matters; The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness; Algorithms of Oppression; How to be an Anti-Racist; The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration; Song of Solomon; Master List of Black Revolutionary Readings, 15+ Books by Black Scholars the Tech Industry Needs to Read Now, The best books on Racism recommended

Courses - Institutionalized Racism: A Syllabus via JSTOR; These 7 courses will teach you how to be anti-racist

Discussions - The path to ending systemic racism in the US; A Mindful Approach to Race and Social Justice; Black Feminism & the Movement for Black Lives

Documentaries - I Am Not Your Negro; 13th; The Class Divide; The Talk - Race in America

Papers - Racial Color Blindness: Emergence, Practice, and Implications; Colorblind and Multicultural Prejudice Reduction Strategies in High-Conflict Situations; The impact of multiculturalism versus color-blindness on racial bias

Podcasts -1619; Code Switch; Armchair Expert with Dax Sheperd; Unlocking Us with Brene Brown; Podcasts that address race and racism head-on; The Anti-Racist Podcast List; 13 Podcasts About Race That'll Further Your Education

Short Videos - Systemic Racism Explained; Why “I’m not racist” is only half the story

TED Talks - Why I, as a black man, attend KKK rallies.; The difference between being "not racist" and antiracist; Racism has a cost for everyone; The symbols of systemic racism — and how to take away their power; 50 years of racism - why silence isn’t the answer

Twittersphere - @FredTJospeh; @DrRachelShelton; @JeffreyASachs

Websites - Dr. Ibram X. Kendi; The Grio; The Root; Race Foreward; Rachel Cargle; Good Black News; Layla F. Saad; Pyramid Project; Talking About Race; Dismantling Racism; Black Live Matter Notion Database

Articles—

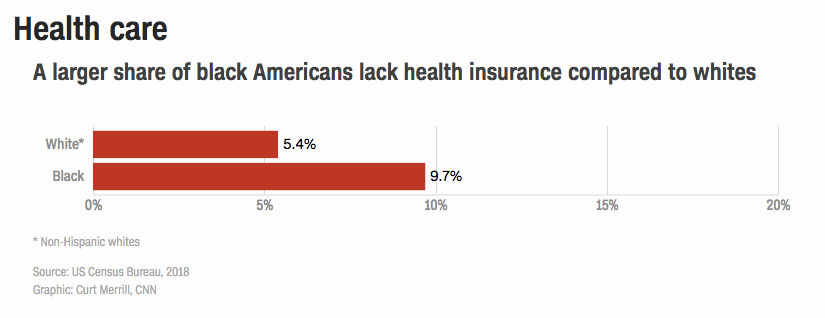

US black-white inequality in 6 stark charts —via CNN

Wealth

Income

Unemployment

Poverty

Health Care

Coronavirus

—

The American Nightmare — via The Atlantic

“To be black and conscious of anti-black racism is to stare into the mirror of your own extinction.

Americans should be asking: Why are so many unarmed black people being killed by police while armed white people are simply arrested? Why are officials addressing violent crime in poorer neighborhoods by adding more police instead of more jobs? Why are black (and Latino) people during this pandemic less likely to be working from home; less likely to be insured; more likely to live in trauma-care deserts, lacking access to advanced emergency care; and more likely to live in polluted neighborhoods? The answer is what the Frederick Hoffmans of today refuse to believe: racism.

Instead, they say, like Donald Trump—like all those raging against the destruction of property and not black life—that they are “not racist.” Hoffman introduced Race Traits by declaring that he was “free from the taint of prejudice or sentimentality … free from a personal bias.” He was merely offering a “statement of the facts.” In fact, the racial disparities he recorded documented America’s racist policies.

Hoffman advanced the American nightmare. What will we advance? Hoffman implied we should let them die. Will we fight for black people to live?

History is calling the future from the streets of protest. What choice will we make? What world will we create? What will we be?

There are only two choices: racist or anti-racist.”

—

Mental Math for a Token: On Calculating My Worth — via LA Review of Books

“That day we had been discussing something about China’s investment in Zimbabwe. The class began like any other class. The professor cold-called somebody to review the basic facts from the case — essentially present what’s at stake for the main protagonist.

As the white guy with the backward colonialism comment stated with such surety, I noticed his seatmate (because what is an elite school without basic terms like “seatmate” taking on extreme significance), a Zimbabwean turning a faint blue-ish purple, because we, darker skin black folks, don’t turn red. She seemed stunned, and while I might have been ready to join her in that shock, I was waiting on another shoe to drop — someone to speak up that didn’t look like me. Someone white, tall, male, WASP-y, and wealthy to enter the dialogue with the confidence that they deserved to speak and the desire to stand with pride that expected adulation for their moment of ally-ship.

Instead, I saw maybe 15 to 20 (my view was limited to about 30 or so folks) of my 93 classmates nod and quietly utter things like “Hadn’t thought of that before” and “Wow, interesting point.” Soon the shock of my Zimbabwean classmate washed over me. I didn’t have to say anything because I knew there was a white guy somewhere in that classroom who was just itching for ally-ship.

I began to wonder: “Maybe I’m not an admission mistake because I’m here to make a fuss and raise hell for moments just like this.” But how could I be indignant without seeming like I’d flown off the handle with my emotions? How could the groundswell of my anger — as a son of parents who grew up in Jamaica, a country that suffered under the hand of British colonialism — be packaged into a succinct “You’re wrong” or the pseudo-respectful response, “Let me push back on that”? And how could I express myself without being simply, incoherently woke?

My mental calculus, like the mental math of many tokens, concluded that my indignation would need validation. Either my hand shot up before my brain could finish processing or the professor sensed my anger through my loud, bated breaths. Before I knew it, I started wrapping “You’re wrong!” with the flowery academic language needed to make myself worthy enough to have an opinion.

I wish that the rules were different — that I didn’t have to wrap the rage that Baldwin said every person of color in America who is relatively conscious is entitled to hold. I wish that I could have communicated the economic toll colonialism takes on people. I wish I could have talked “business talk” about the humanity that suffered under the reckless reign of colonialism. I wish I could have remained calm and that my bald black head didn’t glisten with beads of sweat. I wish I could have quipped “Imagine Holland or the UK without colonialism” — this way my classmates could understand what little the colonized get versus the colonizer.

But instead, sweaty and stammering, I reached for the muses of left-leaning, post-colonialism thinkers more fit for an American Studies class at a school where students walk barefoot, smoke weed, and smell like patchouli.

I tried to recite parts of a Frantz Fanon’s (muse of my post-colonialist persuasion) treatise, The Wretched of the Earth, where Fanon talks at length about the psychological damage incurred by colonization. Even worse, I used the word “treatise.” I talked about the colonial origins of comparative development and the trio of economics scholars who wrote it: Drs. Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson. And of course, I left out their first names so I could sound more like the fancy people who know so many things that they can’t be bothered to say the first names of important people. And at some point, I tried to dazzle whomever managed to continue listening by that point with Mancur Olson’s “roving banditry.” And if I’ve lost you, you’re probably right to have stopped reading just as my classmates stopped listening.

I said a whole lot of everything without saying much of anything, only to have my voice crack and spend nearly four minutes — about 3.5 minutes longer than the ideal HBS comment. My black consciousness came up in the arrears that day. But blathering for validation’s sake dashed my classmate’s opportunity to hear and understand just how wrong he was. Being a token is as much about getting access to the rooms and spaces I’ve been systematically left out of as it is about giving a bunch of other non-marginalized people the opportunity to confirm or negate the biases they have about tokens like me, and how I arrived in that same space.

It isn’t fair that my mental math at that moment had to be so complicated. A lot of my time at HBS was spent stewing in jealousy or at least envying the boldness of the thoughts shared by my white classmate. His math was simple: “Have a thought plus share the thought minus concern for how what you say will be interpreted as too loud, too angry to be indignant equals valuable contribution.” My math? My math for making some meaningful, memorable contribution in class was “Have a thought, but take that thought and question it the millionth power, minus the fervor and emotion that come with important discussions, times your best impression of a voice that your family and friends who look like you from home would never recognize equals a contribution that your white colleagues can hear and not fear.”

And it won’t stop at an HBS classroom. I have felt the same pressure at that moment that I have felt when a co-worker makes an incendiary comment about the curliness or “nappiness” of my hair. I have felt the same when a white high school teacher remarked about the overreach of gains Blacks have attained after the Civil Rights era. In each of those times, I have tried to do the math and as I age the consequences of doing that mental math “properly” only increase. For most of my life, I have used every status symbol imaginable, from Oxford to Harvard, to help institutions like HBS claim diversity. My face on a brochure helped not just my mental math as a token but the math every institution feels compelled to do so they can claim that they are “diverse and inclusive.” But it is precisely my aid to these institutions that causes me to recall Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1966 speech at Southern Methodist University. He said, “If we are to have a truly integrated society, it will never develop through tokenism.”

Bungling that math, on that day, offered me another chance to realize that the status quo would never let me be anything other than a token. The more mental math I do, the more I try to validate my place in elite spaces, the more I do a disservice to everyone who’s not in that room. The more math I do, the clearer it becomes that I’m dedicating my life to validating a system constructed to invalidate me. Not doing the math might cost me a lot — the respect of my classmates and co-workers, my perception as “just as smart,” and maybe a chance to show off that “I belong here too.” But the only way I’ll ever stop being a “token” is if I belong, with no math or validation needed. Maybe it’s time to give up on surviving the status quo. Perhaps, I’m past due to agree with Dr. King when he said, “Tokenism is much more subtle and can be much more depressing to the victims of the tokenism than all-out resistance.”

—

The 1980s crack epidemic was a fork in the road. America chose racism and prisons over public health — via The LA Times Editorial Board

What if the nation had met the crack epidemic of the 1980s with healthcare rather than with police and prison? How much more prepared might we have been today for a deadly viral pandemic, and how much more resilient in the aftermath, had we built out a public health infrastructure with treatment clinics, housing and other resources and supports aimed at restoring the health of American neighborhoods?

What if we had recruited, trained and adequately paid a generation of clinicians, physicians, nurses, researchers, peer counselors and educators to deal with the drug crisis instead of buying tanks and armored cars for police and sending them into neighborhoods suffering the physical and social consequences of cheap crack cocaine?

The 1980s were our fork in the road. The path we chose led directly to the nation we now inhabit, overwhelmed by serious illness, fear, anger, mutual mistrust and a level of inequity and incompetence that mocks our self-image as Americans.

To know what to do now, it’s essential to remember what we didn’t do then.

We are called to respond differently this time. We must do now what we failed to do then: Build a system of care that fosters health and justice, and deconstruct the costly police-and-prisons infrastructure that we foolishly built instead.

We need not start from scratch. Los Angeles County helps people coming home from jail or prison reunify with their families and get jobs, housing and care. The Office of Diversion and Reentry — housed, it’s important to note, in the Health Department — is the leading edge of a broader care-first, jails-last program that, if built out as envisioned by frontline service providers and county workers, could be the system that we should have built more than three decades ago. It could be a model for the nation.

The L.A. County Board of Supervisors adopted a framework for the care-first program, formally known as Alternatives to Incarceration. But then came the current health crisis, and implementation has stalled. It would be ironic — and tragic — if the program is mothballed because the pandemic and the reaction to Floyd’s killing turn the county’s attention elsewhere. Might we, in 30 years, look back again at the road we should have taken but didn’t?”

—

Identity Politics and Elite Capture — via Boston Review

“The black feminist Combahee River Collective manifesto and E. Franklin Frazier’s Black Bourgeoisie share the diagnosis that the wealthy and powerful will take every opportunity to hijack activist energies for their own ends.

Such elite capture threatens a whole group’s value structure, as everyone is confronted with this simplified version of the initial values and incentives to adopt it. This can tend, over time, to push understandings of the group values—both by those in the group and outside of it—toward the elites’ simpler direction.

There is another crucial insight that can be gained from applying the analogy of games to our discussion of elite capture. Design decisions structure a game’s built environment, baking the outlook of designers into the decisions players are faced with. In similar fashion, elite decision-making determines what options are available to non-elites. This is precisely the role that the press, social media influencers, military top brass, and titans of capital have in our lives. That is, they frame the conditions of work (and play) for the rest of us.

This helps to illuminate developments in black elite politics since Frazier wrote in the 1950s. In Frazier’s time, there were class differences among African Americans, but exceedingly few black Americans had notable political power or the level of wealth that could buy serious influence. But that has changed, as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor points out:

The most significant transformation in all of black life over the last fifty years has been the emergence of a black elite, bolstered by the black political class, that has been responsible for administering cuts and managing meager budgets on the backs of black constituents.

This transformation was dramatically on display in Baltimore during the protests of the murder of Freddie Gray. Taylor continues: “when a black mayor, governing a largely black city, aids in the mobilization of a military unit led by a black woman to suppress a black rebellion, we are in a new period of the black freedom struggle.”

In the preface to the 1962 edition of Black Bourgeoisie, Frazier points out a key demographic that he would have been forced to consider if he were to write the book again: the participants of the sit-ins and other social movements against racial segregation. When asked by a reviewer to envision an alternative black elite that didn’t merit the scathing criticism he gave to the present one, these activists served as his answer.

This is a start, but not enough. As the Combahee River Collective acknowledged, simply participating in activism is no guarantee that we will develop the right kind of political culture; its founding members were veterans of important radical political movements that nevertheless made crucial oversights along the way. Elites have to get involved—actually involved—but that involvement needs to resist elite capture of values and the gamification of political life.

We have our work cut out for us, but fortunately we aren’t starting from scratch: there’s a rich history to draw from. In the 1960s, feminists held regular group meetings, in houses and apartments, to discuss gender injustice in ways that would have been taboo in mixed company. A set of such “consciousness raising” guidelines by Barbara Smith and fellow activists Tia Cross, Freada Klein, and Beverly Smith provides an example of identity politics work as the Combahee River Collective envisioned it. The exercise starts by asking participants to examine their own shortcomings (“When did you first notice yourself treating people of color in a different way?”), but ends by asking how they can use an element of shared oppression as a bridge to unite people across difference (“In what ways can shared lesbian oppression be used to build connections between white women and women of color?”). Because, in the end, we’re in it together—and, from the point of view of identity politics, that is the whole point.”

—

Predatory Inclusion — via N+1 Mag

“Gould liked the direction the new rules were heading in, but had some reservations: “It does show FHA is finding the strength and guts to stand up to the mortgage companies,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “But I don’t think it is the answer.” He explained further: “This fails to put FHA on the line. The whole problem is to get good inspections. I think FHA has to be held responsible for that. I don’t think it’s fair to try to just put it all on the mortgage companies.” For Gould, the FHA was still shirking its responsibilities as a public agency by clinging to its hands-off approach. “This is typical of FHA in not recognizing that they are responsible for some of these things,” he said.

By 1974, the experiences of the four women from Seattle had been multiplied thousands of times as complaints and legal action against HUD-FHA mounted. The stories of low-income homeowners, predominately women, from across the country were critical for multiple reasons. Foremost was the willingness of Perry, Foster, Coleman, and Cook — and many others like them — to make their deplorable housing situations publicly known, which acted as a catalyst in exposing the malfeasance, corruption, and fraud pervasive in HUD-FHA’s transactions in its subsidized and unsubsidized, existing and new housing programs. The public proclamations of these disproportionately African American and almost always poor women offered a counternarrative to HUD and Romney’s popular argument that these homeowners were ultimately responsible for the poor condition of their homes. Their demands and their willingness to file lawsuits and fight for their rights as homeowners threatened to upend the preconceived notions of these women as undeserving, unprepared, and unsophisticated.

Still, some analysts insisted that the failure of HUD’s homeownership programs was proof positive that poor people were ill equipped for the responsibilities of homeownership. It was easy to extrapolate the implications, to get more specific: low-income African Americans were not capable homeowners. While others pointed to HUD’s obvious mismanagement of its programs as the real culprit in their demise, the fundamental lessons of HUD’s experiment were muddled by economic sensibilities, including the commitment to private property and the centrality of homeownership to the American economy, which would remain pervasive long after the retreat from the postwar racial liberalism of the 1970s.

The assumption that a mere reversal of exclusion to inclusion would upend decades of institutional discrimination underestimated the extent to which the housing economy was organized around race and property. Discriminatory differentials were embedded in the US housing market, based on a combination of historical and continuing practices within the real estate, housing, and banking industries — abetted by the failure of the federal government, in any historical period, to enact rigorous regulatory compliance with civil rights laws. Even when the terms were created to make homeownership possible for poor and working-class Black people, their economic disadvantage was impossible to overcome. Racial difference and antipathy are not unintended consequences of the market; they constitute it.”

—

Why So Many Organizations Stay White — via Harvard Business Review

“Many attempts to intervene in racial inequality assume that discrimination is a rare event, the intentional actions of bad (or at least unenlightened) actors. Employers choosing to hire a white felon before a black person without a criminal record or research that shows employers are 50% more likely to call back equally qualified job applicants with “white-sounding” names are important examples of the individual approach. And many Americans readily acknowledge white power when it is tied to brazen spectacles like the 2018 neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville; the violence of white-supremacist events and the odiousness of the accompanying racial ideology make such displays easy to condemn.

Evidence of individual discrimination is obviously important. But these bad-actor or explicit views cannot account for the broad empirical patterns of organizational segregation and the deeply unequal distribution of organizational resources. It is also important to think about how the normal (and legal) functions of predominately white organizations gain from and exacerbate racial inequalities. Current legal remedies for discrimination rely on the bad-actor model. Employees can potentially sue for intentional discrimination, for example, if an employer uses a racial epithet. However, these legal remedies would have little to say about discretionary promotion procedures that may favor white employees or a business choosing to locate in a neighborhood that makes them inaccessible to people of color because of residential segregation. Indeed, this latter active discrimination may become moot if poor access to public transportation and long travel times weed people of color out of hiring pools.

I encourage scholars and managers to think about how organizations create and distribute resources along racial lines in ways that may not necessarily be considered legally illegitimate or discriminatory but may nonetheless shape racial inequality. Hospitals that provide substandard care have contributed to the staggering statistic that black women are 243% more likely to die in childbirth than white women. Schools that provide a substandard education for black students contribute to the so-called achievement gap. And churches more dedicated to segregated schools than racial equality have contributed to the country’s growing racial polarization. In each of these cases, thinking that the organization in question has nothing to do with race may be especially harmful, as it assumes that only the active animus of physicians, teachers, or clergy — not the everyday tasks of providing health care or disciplining students — could produce racially unequal outcomes. Assuming race neutrality disregards the vast historical evidence of the centrality of race in shaping American organizations. Ignoring how white organizations help to perpetuate racial harms virtually guarantees that these harms will continue. It is safer, and likely more realistic, to start with the assumption that organizations are contributing to racial inequality unless the data shows otherwise.

There are no easy answers when it comes to creating more diverse and equitable environments. And given how deeply American organizations have been shaped by racial inequality, I am not hopeful that the type of structural changes needed to make organizations more equitable will appear on the horizon anytime soon. Colleges and universities are retreating from successful affirmative action policies, organizational segregation is persistent, and whiteness is a key credential for moving up organizational hierarchies. At a minimum, leaders should stop thinking about discrimination and inequality as rare events and understand that racial processes often shape behavior in the absence of ill-intent. Conversations about organizational inequality need to refocus from a narrow concern with feelings and racial animus to the massive inequalities in material and psychological resources that organizations distribute between racial groups. Recent calls for reparations can provide a model, as these have forced some organizations to reckon with how their roots in slavery contribute to continued racial inequality. Leaders could also begin to examine how their decisions about location and hiring, among other choices, exacerbate inequalities. White organizations have attempted to deal with racial inequality while wielding meager tools. Organizations that are serious about changing patterns of racial inequality need to move beyond diversity and inclusion and toward reparations and restitution.”

—

The Coronavirus Was an Emergency Until Trump Found Out Who Was Dying — via The Atlantic

“The pandemic has exposed the bitter terms of our racial contract, which deems certain lives of greater value than others.

The underlying assumptions of white innocence and black guilt are all part of what the philosopher Charles Mills calls the “racial contract.” If the social contract is the implicit agreement among members of a society to follow the rules—for example, acting lawfully, adhering to the results of elections, and contesting the agreed-upon rules by nonviolent means—then the racial contract is a codicil rendered in invisible ink, one stating that the rules as written do not apply to nonwhite people in the same way. The Declaration of Independence states that all men are created equal; the racial contract limits this to white men with property. The law says murder is illegal; the racial contract says it’s fine for white people to chase and murder black people if they have decided that those black people scare them. “The terms of the Racial Contract,” Mills wrote, “mean that nonwhite subpersonhood is enshrined simultaneously with white personhood.”

The racial contract is not partisan—it guides staunch conservatives and sensitive liberals alike—but it works most effectively when it remains imperceptible to its beneficiaries. As long as it is invisible, members of society can proceed as though the provisions of the social contract apply equally to everyone. But when an injustice pushes the racial contract into the open, it forces people to choose whether to embrace, contest, or deny its existence. Video evidence of unjustified shootings of black people is so jarring in part because it exposes the terms of the racial contract so vividly. But as the process in the Arbery case shows, the racial contract most often operates unnoticed, relying on Americans to have an implicit understanding of who is bound by the rules, and who is exempt from them.

The implied terms of the racial contract are visible everywhere for those willing to see them. A 12-year-old with a toy gun is a dangerous threat who must be met with lethal force; armed militias drawing beads on federal agents are heroes of liberty. Struggling white farmers in Iowa taking billions in federal assistance are hardworking Americans down on their luck; struggling single parents in cities using food stamps are welfare queens. Black Americans struggling in the cocaine epidemic are a “bio-underclass” created by a pathological culture; white Americans struggling with opioid addiction are a national tragedy. Poor European immigrants who flocked to an America with virtually no immigration restrictions came “the right way”; poor Central American immigrants evading a baroque and unforgiving system are gang members and terrorists.

The coronavirus epidemic has rendered the racial contract visible in multiple ways. Once the disproportionate impact of the epidemic was revealed to the American political and financial elite, many began to regard the rising death toll less as a national emergency than as an inconvenience. Temporary measures meant to prevent the spread of the disease by restricting movement, mandating the wearing of masks, or barring large social gatherings have become the foulest tyranny. The lives of workers at the front lines of the pandemic—such as meatpackers, transportation workers, and grocery clerks—have been deemed so worthless that legislators want to immunize their employers from liability even as they force them to work under unsafe conditions. In East New York, police assault black residents for violating social-distancing rules; in Lower Manhattan, they dole out masks and smiles to white pedestrians…

The frame of war allows the president to call for the collective sacrifice of laborers without taking the measures necessary to ensure their safety, while the upper classes remain secure at home. But the workers who signed up to harvest food, deliver packages, stack groceries, drive trains and buses, and care for the sick did not sign up for war, and the unwillingness of America’s political leadership to protect them is a policy decision, not an inevitability. Trump is acting in accordance with the terms of the racial contract, which values the lives of those most likely to be affected less than the inconveniences necessary to preserve them. The president’s language of wartime unity is a veil draped over a federal response that offers little more than contempt for those whose lives are at risk. To this administration, they are simply fuel to keep the glorious Trump economy burning….

The president’s cavalier attitude is at least in part a reflection of his fear that the economic downturn caused by the coronavirus will doom his political fortunes in November. But what connects the rise of the anti-lockdown protests, the president’s dismissal of the carnage predicted by his own administration, and the eagerness of governors all over the country to reopen the economy before developing the capacity to do so safely is the sense that those they consider “regular folks” will be fine.

Many of them will be. People like Ahmaud Arbery, whose lives are depreciated by the terms of the racial contract, will not.”

Books—

Personal Recommendations:

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander

The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration by Isabel Wilkerson

Reading List Recommendations:

Master List of Black Revolutionary Readings via shared G-Drive document

The best books on Racism recommended by Kurt Barling via Five Books

Courses—

Institutionalized Racism: A Syllabus via JSTOR

“Institutional racism—a term coined by Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture) and Charles V. Hamilton in their 1967 book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America—is what connects George Floyd and Breonna Taylor with Ahmaud Arbery, Philando Castile, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Emmett Till, and the thousands of other people who have been killed because they were “black in America.”

This context seems vital for discussions both inside and outside the classroom. The following articles, published over the course of JSTOR Daily’s five years try to provide such context. As always, the underlying scholarship is free for all readers. We have now updated this story with tagging for easier navigation to related content, will be continually updating this page with more stories, and are working to acquire a bibliographic reading list about institutionalized racism in the near future. (Note: Some readers may find some of the stories in this syllabus or the photos used to illustrate them disturbing. Teachers may wish to use caution in assigning them to students.)”

—

These 7 courses will teach you how to be anti-racist via Fast Company

“These courses were developed by Black women, and will teach you to recognize and work against racism.”

Rachel Cargle: #dothework free 30-day Course and The Great Unlearn

Nova Reid: Anti-Racism & Diversity Matters

Boukman Academy

Rachel Ricketts: Spiritual Activism

Monique Melton: Unity Over Comfort

Austin Channing Brown: The ACB Academy

Layla F. Saad: Good Ancestor Academy

Discussion—

The path to ending systemic racism in the US via TED

A Mindful Approach to Race and Social Justice | Rhonda Magee, Jon Kabat-Zinn, Anderson Cooper via Wisdom 2.0

Black Feminism & the Movement for Black Lives: Barbara Smith, Reina Gossett, Charlene Carruthers

Documentaries—

I Am Not Your Negro

13th

A Class Divided

The Talk - Race in America

Papers—

Racial Color Blindness: Emergence, Practice, and Implications

Colorblind and Multicultural Prejudice Reduction Strategies in High-Conflict Situations

The impact of multiculturalism versus color-blindness on racial bias

Podcasts—

Shows:

Episodes:

Lists:

Podcasts that address race and racism head-on via Radio Republic

13 Podcasts About Race That'll Further Your Education via Women’s Day

Short Video—

Systemic Racism Explained via Act.tv

—

Why “I’m not racist” is only half the story | Robin DiAngelo | Big Think

TED Talks—

50 years of racism - why silence isn’t the answer | James A. White Sr. | TEDxColumbus

The symbols of systemic racism — and how to take away their power | Paul Rucker

Racism has a cost for everyone | Heather C. McGhee

The difference between being "not racist" and antiracist | Ibram X. Kendi

Why I, as a black man, attend KKK rallies. | Daryl Davis | TEDxNaperville

Twittersphere —

Websites —

That’s it for this week. Until next time - Ad Astra!

More on Eclectic Spacewalk:

Subscribe to Substack Newsletter

Listen to all podcasts on Anchor

Follow Eclectic Spacewalk on Twitter