Read previous post #8 - Four Narratives of Narrative Economics (25 minutes)

Table of Contents:

Consilience—

Part I

Rumsfeld’s knowns & unknowns

An enchantment from ancient Ionia

Common foundations for explanation

Part II

Known Knowns

Known Unknowns

Unknown Unknowns

Unknown Knowns

Part III

Putting it all together through a protopia lens

Audio (1 audiobook, 4 podcasts)

Video (1 TED talk, 1 lecture, 2 videos)

What’s Next?

Reading Time: 15 minutes (Read the sections you find intriguing, bookmark the media/links, and come back to anytime.)

Consilience—

Abstract: “Consilience is the linking together of principles from different disciplines especially when forming a comprehensive theory. It is a metaphysical worldview that it is possible (at least in theory) to unite all forms of knowledge."

Part I

In February of 2002, the world was given one of the greatest soundbites in media history. Albeit the statement being somewhat logical, philosophically valid, and actually an efficient manner of distilling complex information it will live on in infamy.

Former US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld replied to a question about Iraq having Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs) with the following:

“Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns -- the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.”

Adaptability, pattern recognition, and the ability to experience awe are possible evolutionary characteristics that are (more) distinct in the human species. Uncertainty of all flavors has, over millennia, molded humanity into the inquisitive and curious creatures we are. To deal with this ironic certainty of uncertainty that our environment produces, we have built up certain mechanisms to point out and hold onto perfection at the highest of costs. We are obsessed, or better yet plagued, by the idea of “perfect,” idolizing “otherworldly” beings that were not “mortal” like we peons. This understanding of our own mortality has been propelled in tandem with the long-standing belief that the world is orderly and can be explained rather simply.

The philosopher Thales of Miletus in Ionia lived in 6th-century ancient Greece. He was given the title of “founder of the physical sciences” by Aristotle some centuries later. What set Thales apart was an enchantment that everything was unified at some fundamental level, including that all matter was ultimately water. The basic idea was that if we have enough unified knowledge about enough things, then we will understand who we are and why we are here. The feeling was as old as civilization itself, mingling with religious tenets in a uniquely different way, focusing on “searching for” objective reality more than “it being revealed to you.”

That conviction in unity was finally given a proper name in the mid-19th century after the Enlightenment swept across the globe. The term “consilience” was first used by William Whewell in his work The Philosophy of Induction, published in 1840. Whewell explains, “the Consilience of Inductions takes place when an Induction obtained from one class of facts, coincides with an Induction, obtained from another different class. This Consilience is a test of the truth of the Theory in which it occurs.”

Edward O. Wilson has recently re-popularized the term with his 1998 book Consilience, on which much of this essay is based. He has made the meaning a bit more accessible to the layman: “a jumping together of knowledge by the linking of facts and fact-based theory across disciplines to create a common groundwork of explanation.” This is an ambitious goal, and may ultimately be folly to pursue without a distinct self-doubting nature baked into the system. We must never subject ourselves to the utopic route of perfections, and adhere to a more incremental and Protopic approach in continued steps that do not ‘end.’

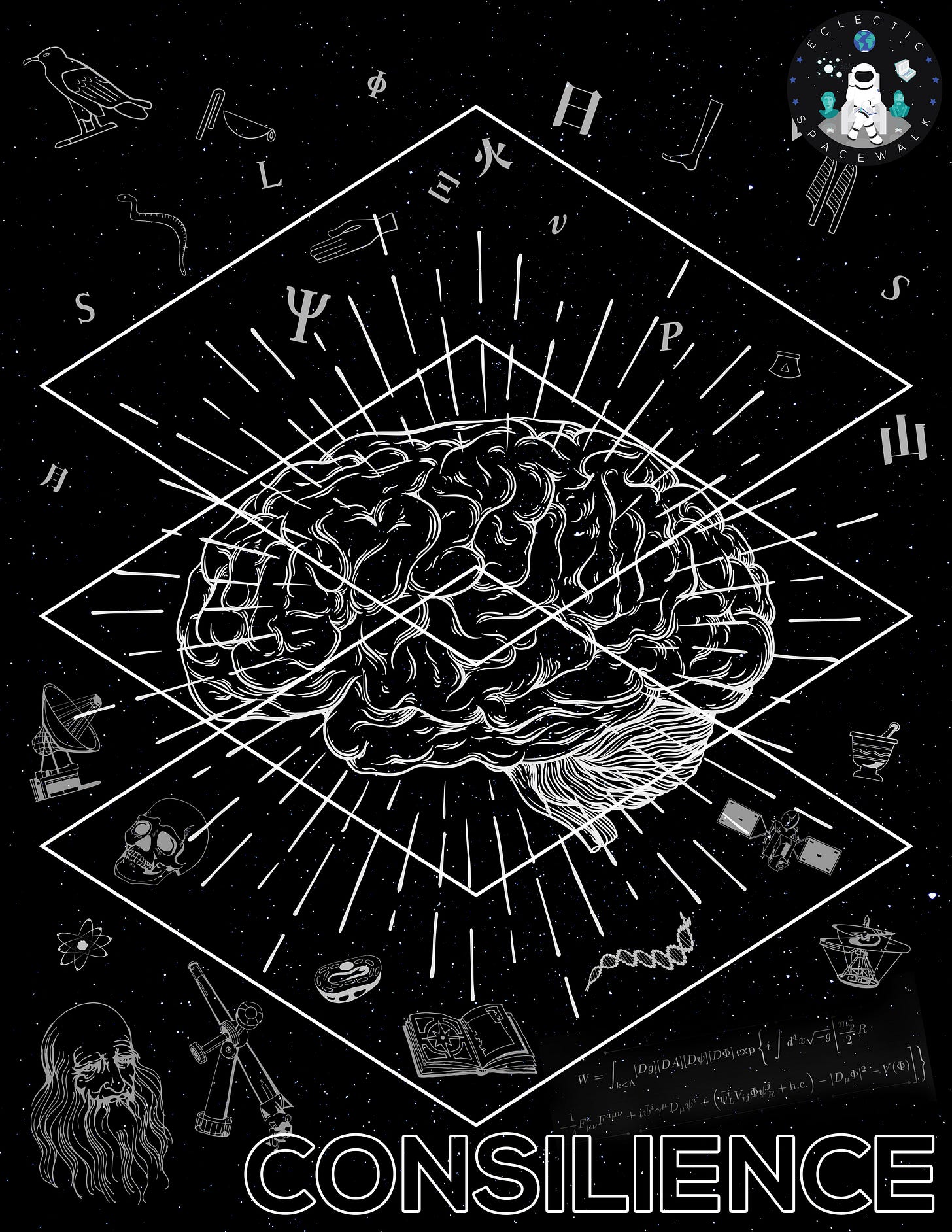

(Graphic via JT Velikovsky’s post on Consilience)

Wilson explains exactly what he believes consilience is and is not: “The belief in the possibility of consilience beyond science and across the great branches of learning is not yet science. It is a metaphysical worldview, and a minority one at that, shared by only a few scientists and philosophers. It cannot be proved with logic from first principles or grounded in any definitive set of empirical tests, at least not by any yet conceived. Its best support is no more than an extrapolation of the consistent past success of the natural sciences. Its surest test will be its effectiveness in the social sciences and humanities, the strongest appeal of consilience is in the prospect of intellectual adventure, and given even modest success, the value of understanding the human condition with a higher degree of certainty.”

Wilson uses an example to illustrate how consilience comes to be through confusion, then rational inquiry, then finally connections. Think of how the subjects below differ and how they intersect. Each body of knowledge is distinct in its own way, but there is a vast understanding through the sciences that a multidisciplinary approach can garner next level results by using one’s success in a field as a possible case in another field.

“We already intuitively think of these four domains as closely connected, so that rational inquiry in one informs reasoning in the other three. Yet, undeniably, each stands apart in the contemporary academic mind. Each has its own practitioners, language, modes of analysis, and standards of validation. The result is confusion, and confusion was correctly identified by Francis Bacon four centuries ago as the most fatal of errors, which “occurs wherever argument or inference passes from one world of experience to another,” says Wilson.

Wilson shows us that any knowledge already has consilient properties, and once we begin to inquire about a subject, there are rings of understanding that interact across a vast lattice of interconnected principles and truths. These are always in progress, but if we are imaginative we can come to *some* fundamental analysis - however short-lived & shortsighted.

Wilson explains what we can garner from these illustrations of thought: “As we cross the circles inward toward the point at which the quadrants meet, we find ourselves in an increasingly unstable and disorienting region. The ring closest to the intersection, where most real-world problems exist, is the one in which fundamental analysis is most needed. Yet virtually no maps exist. Few concepts and words serve to guide us. Only in imagination can we travel clockwise from the recognition of environmental problems and the need for soundly based policy; to the selection of solutions based on moral reasoning; to the biological foundations of that reasoning; to a grasp of social institutions as the products of biology, environment, and history. And then back to environmental policy.”

In the late 1990s, Wilson was considering another example that we still today have no solution for. What is the best policy that governments everywhere should use to regulate the dwindling forest reserves of the world? (Take out forests and add in any of the following: melting ice caps, wild fish populations, urban expansion into animal habitats, ecological degradation.) Wilson shows how important the idea of consilience is in theory, but also how difficult in practice that becomes for both intellectuals and the general public that policy serves.

“There are few established ethical guidelines from which agreement might be reached, and those are based on an insufficient knowledge of ecology. Even if adequate scientific knowledge were available, there would still be little basis for the long-term valuation of forests. The economics of sustainable yield is still a primitive art, and the psychological benefits of natural ecosystems are almost wholly unexplored...This is not an idle exercise for the delectation of intellectuals. How wisely policy is chosen will depend on the ease with which the educated public, not just intellectuals and political leaders, can think around these and similar circuits, starting at any point and moving in any direction.”

(Graphic via JT Velikovsky’s post on Consilience)

Let’s have some fun with examples and thought experiments inspired by the former Mr. Rumsfeld, with an addition from our favorite Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek. These are by no means exhaustive, or even the best ways to explain, but come subjectively from my own consilient worldview.

—

Part II

Known Knowns: things we know we know (Facts)

The scientific method is described as a continual process of testing hypotheses through experimentation. This simple yet effective rubric has allowed us to expand our insights in the smallest and largest scales of our shared reality. The fact that we know any of the levels that we see below is mind-boggling. A dual-minded organism of doubt and appreciation has probed its outer and inner environment to fundamental levels of understanding. Extraordinary!

(Graphic via JT Velikovsky’s post on Consilience)

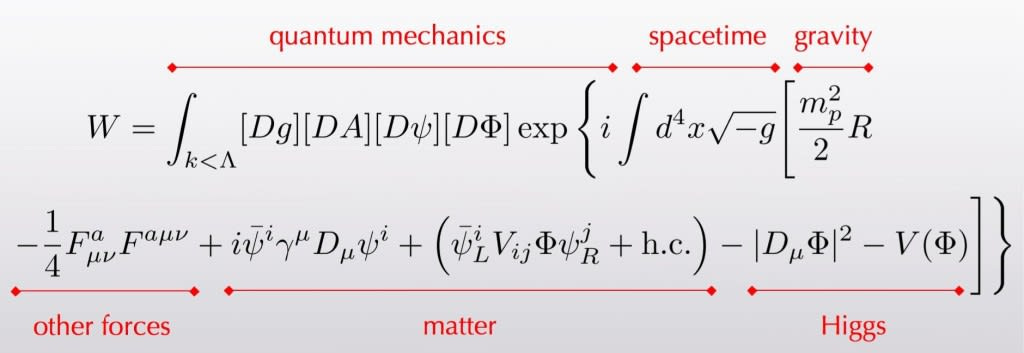

A few other highlights that show our current known knowns of matter, scale, and time that we should be immensely proud of:

Closest “Scientific Theory of Everything” but not a “real” theory of everything

“This is the amplitude to undergo a transition from one configuration to another in the path-integral formalism of quantum mechanics, within the framework of quantum field theory, with field content and dynamics described by general relativity (for gravity) and the Standard Model of particle physics (for everything else). The notations in red are just meant to be suggestive, don’t take them too seriously…No experiment ever done here on Earth has contradicted this model.” - Physicist Sean Carrol

—

Known Unknowns: we know there are some things we do not know (Hypotheses)

The Latin maxim “ignoramus et ignorabimus” means "we do not know and will not know.” There will always be knowledge that we will never gain. There will always be information that we can never acquire, even if we know about its theoretical existence. There is also all the “lost knowledge” throughout our entire history that we will never know without a time machine.

(Video via The Feynman Series)

Our knowledge can change over time. We have instances of known unknowns becoming known knowns with the discovery of the planet Neptune using mathematics (unknown perturbations to other planets’ orbits made predictions on where to find it), the confirmation of Albert Einstein’s theories through the observations of gravitational waves via LIGO, and finds of “nuclear glass” across the globe.

We also have examples of when known knowns became known unknowns such as: how to make the popular and ancient psychedelic beverage soma being lost to the ages, the ancient library of Alexandria being destroyed along with all of its preagricultural secrets, and the collective knowledge lost through conquests over the ages (including the Vikings, Mongols, Crusades, and Nazi book burning).

The real problem of consciousness, what exactly is outside the observable universe, how humans will only ever know or use a finite set of integers, and how our understanding can change over time are other interesting thought experiments regarding known unknowns.

—

Unknown Unknowns: we don't know we don't know (Could be anything)

The philosopher Jerry Fodor once wrote, "The success of the sciences is one thing: the unity of science is quite another." Our incompleteness of knowledge gives us our real power. We will never know all the “right” questions to ask, and that is acceptable because it makes us human and can illuminate how humans are truly creative.

There will always be a knowledge base that is outside our collective purview, and that is the epitome of unknown unknowns. In economics, this is referred to as Knightian Uncertainty. There is always something new that can happen with the passage of time so that increases uncertainty and possibly risk. We don’t know what we don’t know!

(Video via Terrence McKenna)

It is quite a difficult matter to ponder about things we don’t know because our basis of questioning is fundamentally tied to our knowings. There will always be hidden universes! There will always be questions regarding simulation theory, the multiverse hypothesis, and anything “outside” our reality.

And this is a good thing, says Bertrand Russell, “Thus, while our knowledge of what is has become less than it was formerly supposed to be, our knowledge of what may be is enormously increased. Instead of being shut in within narrow walls, of which every nook and cranny could be explored, we find ourselves in an open world of free possibilities, where much remains unknown because there is so much to know.”

—

Unknown Knowns (Intuitions & Prejudices)

Philosopher Slavoj Žižek says that there is an often-overlooked fourth category, unknown knowns. In psychology, it is the Freudian unconscious, or sometimes rearing its head as the cognitive bias Dunning–Kruger effect.

"If Rumsfeld thinks that the main dangers in the confrontation with Iraq were the 'unknown unknowns', that is, the threats from Saddam whose nature we cannot even suspect, then the Abu Ghraib scandal shows that the main dangers lie in the ‘unknown knowns’—the disavowed beliefs, suppositions and obscene practices we pretend not to know about, even though they form the background of our public values,” says Zizek.

Other examples that have our prejudices baked in: how the victors usually write history, humans ALWAYS encode bias into tech and AI, narrative management through media/culture, and how we teach children differently by what we teach them.

(Video via Philosophy Overdose)

—

Part III

The idea of consilience can be quite utopic, and thus is dismissed by some. It has built upon our successes in the sciences and wants to bring the arts and humanities into unity. But we need to be honest about our shortcomings and the possibility we may, but probably never will have consilience.

Instead of a utopian lens, we should employ a protopian one in which we have incremental progress in steps toward improvement - not perfections. We should strive for perfection, knowing full well that it is unattainable, and when we fall short we will have observed more and gained experience to make better predictions in how best to strive for perfection in the future.

We have reason to be optimistic that we are moving toward consilience given the success of knowledge in the natural sciences, says Wilson, “To ask if consilience can be gained in the innermost domains of the circles (first diagram in part I), such that sound judgment will flow easily from one discipline to another, is equivalent to asking whether, in the gathering of disciplines, specialists can ever reach agreement on a common body of abstract principles and evidentiary proof. I think they can. Trust in consilience is the foundation of the natural sciences.”

(Graphic via JT Velikovsky’s post on Consilience)

A new future across many different disciplines in various degrees will hybridize our knowledge in ways we have never dreamed of. “For the material world at least, the momentum is overwhelmingly toward conceptual unity. Disciplinary boundaries within the natural sciences are disappearing, to be replaced by shifting hybrid domains in which consilience is implicit. These domains reach across many levels of complexity, from chemical physics and physical chemistry to molecular genetics, chemical ecology, and ecological genetics. None of the new specialties is considered more than a focus of research. Each is an industry of fresh ideas and advancing technology,” says Wilson.

Here is to a more consilient future for us all!

Audio—

https://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/0000a60c-4124-1498-812483414b7f0000/

https://will.illinois.edu/focus/program/consilience-the-unity-of-knowledge

http://rationallyspeakingpodcast.org/show/rs63-consilience-the-unity-of-knowledge.html

Video Playlist—

My Wish: To build the encyclopedia of life

Supertheories and Consilience from Alchemy to Electromagnetism

To understand is to recieve patterns - Jason Silva

It all goes together - Alan Watts

What’s Next?

The next newsletter will be on Our Second Psychedelic Renaissance

If you enjoyed this post, please share with other potential eclectic spacewalkers, consider subscribing or gift a subscription, or connect with us on social media to continue the conversation! Also, I am an advocate of Bitcoin. My address is on my About.Me page if you are feeling extra curious.

Subscribe to Substack Newsletter

Listen to all podcasts on Anchor

Follow Eclectic Spacewalk on Twitter

Thank You for your time. Until the next post, Ad Astra!