Eclectic Spacewalk #7 - Terrestrial Politics

A theoretical approach to the political reorganization of every Terrestrial being’s dwelling place

Table of Contents:

Terrestrial Politics—

“Homo Economicus”

Neo-liberalism

This time is different

Getting back Down to Earth

De-familiarizing like a Martian

Out of this World

Attractor 3 & The Terrestrial

Out of the Wreckage

Belonging

Community

Subsidiarity

Audio (1 audio-book, 2 podcasts)

Video (8 videos)

What’s Next?

Reading Time: 20 minutes (Read sections you find intriguing, bookmark the media/links, and come back to anytime.)

Terrestrial Politics—

Abstract: “A theoretical approach to the political reorganization of every Terrestrial being’s dwelling place (within Earth’s “Critical Zone”), including its own way of identifying what is local, what is global, and of defining its entanglements with other beings.”

Currently, the globe is experiencing an “Out of this World” mind contagion in its political spheres. Since Donald J. Trump’s election, one could argue fairly easily that we are now in an era where politics-oriented toward any identifiable goal has ended. French philosopher Bruno Latour claims this lost viewpoint is purposeful, “as Trumpian politics is not “post-truth,” but post-politics - that is, literally, a politics with no object, since it rejects the world that it claims to inhabit.”

In his book Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climate Regime, Latour doesn’t mince words in discussing the leading phenomenon in world affairs which began long before Trump got elected: “a systematic effort to deny the existence of climate change. “climate” here refers to the relations between human beings and the material conditions of their lives.” (Take note of how he defines “climate” in what a human deals with in terms of their environment, also known as Earth’s critical zone.) Increased inequality and global deregulation are the other two phenomena that Latour points to. The subsequent rise of populism, and the honest realization that governments are not immune to the effects of what the Founder and Executive Chairman of the World Economic Forum, Klaus Schwab, calls The Fourth Industrial Revolution. These trends are also considered in our equation.

Some history is needed to understand just how far off the path we truly are. Do you remember reading the work of Thomas Hobbes? Does Leviathan ring a bell? In his most famous text, Hobbes asserted that life’s position in the state of nature is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Life’s, not just humans’, base operating system is a war of everyone against everyone else. But this statement was made in 1651 and must be taken with a truckload of salt with its basis in religion and original sin.

Remember the work of J. S. Mill? No? Well in the 19th century, the British philosopher proposed that we humans have surpassed our genetic predisposition of “Homo Sapiens,” and faux-upgraded to be “Homo-Economicus” “or "economic man." This says that each human is a rational person who pursues wealth for their own self-interest. First it was a thought experiment, then it was used as a modeling tool to strive toward an ideal, and lastly, it changed our perceptions of ourselves. The way we behave is due to our perceptions. The story of our self-maximizing and competitive nature was told so often, usually with little critique, that we have accepted it as an account of who we really are.

“Homo Economicus” is a reasonable description of chimpanzees, but hardly of humans. In their illuminating psychology journal paper, Keith Jensen, Amrisha Vaish, and Marco F. H. Schmidt remind us, “The fact that humans cooperate with non-kin is something we take for granted, but this is an anomaly in the animal kingdom. Our species’ ability to behave prosocially may be based on human-unique psychological mechanisms.”

They argue that “these mechanisms include the ability to care about the welfare of others (other-regarding concerns), to “feel into” others (empathy), and to understand, adhere to, and enforce social norms (normativity). [They] consider how these motivational, emotional, and normative substrates of prosociality develop in childhood and emerged in our evolutionary history. Moreover, [they] suggest that these three mechanisms all serve the critical function of aligning individuals with others: Empathy and other-regarding concerns align individuals with one another, and norms align individuals with their group.”

The kind of large-scale cooperation seen uniquely in humans is mainly due to this alignment. Our “spectacularly unusual when compared to other animals” nature says that we also cannot cope alone. Humans need connection & togetherness, just as much as we need food and shelter. I assume this is latent knowledge for most people, but the market(s), politics, and the sense of possibility evaporating in front of our eyes make a compelling case for not needing food, usually at the expense of shelter. The result of this belief being taken as canon is the loss of a common purpose. A lack of common purpose is a leading reason why Anomie is more common than ever.

It is exacerbated by “Shifting Baseline Syndrome,” a term describing ecosystems in biology used to understand how people respond to political change after years of being immersed in hedonic propaganda, “Over the generations, we adjust to almost any degree of deprivation or oppression, imagining it to be natural and immutable.”

—

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism, like any political narrative, has to account for who and why we are. We are “homo economicus,” and we are competitors doing all that we can to get ahead of our fellows. As I have just shown, this is not necessarily the case, but we need to dig deeper for the deep and pernicious roots of “homo economicus” before we offer up an alternative.

In his book Out of the Wreckage: A New Politics for an Age of Crisis, George Monbiot says that Neoliberalism's central claim is for society to make maximizing profits humanity’s aim and purpose. “Defined by the market, defined as a market, human society should be run in every aspect as if it were a business, its social relations reimagined as commercial transactions; people redesigned as human capital,” goes Neoliberalism's claims.

Monbiot says our dominant political narrative has become so pervasive that we hardly question its reach - effectively hiding it. The ability to see it as a power-relations-based ideology has become literally blasphemous.

He goes on, “Efforts to create a more equal society are both counterproductive and morally corrosive...Attempts to limit competition are treated as hostile to liberty. Tax and regulation should be minimized; public services should be privatized or reconstructed in the image of the market. The organization of labor and collective bargaining by trade unions are portrayed as market distortions that prevent the real winners and losers from being discovered. Inequality is recast as virtuous: a reward for usefulness and a generator of wealth, which trickles down to enrich everyone.”

Losers are defined, and self-defined, in a competitive world as those who fall behind because people can ALWAYS change their situation by exercising choice through spending, says Neoliberal theory.

“Neoliberalism turns the oppressed worker into a free contractor, an entrepreneur of the self. Today, everyone is a self-exploiting worker in their own enterprise. Every individual is master and slave in one. This also means that class struggle has become an internal struggle with oneself. Today, anyone who fails to succeed blames themselves and feels ashamed. People see themselves, not society, as the problem,” says philosopher Byung-Chul Han.

Until we name and describe a narrative, then we cannot contest it. Neoliberalism has stuck around for much longer than needed, due to its anonymity and the absence of countervailing stories. “To change the world, you must tell a story: a story of hope and transformation that tells us who we are,” says Monbiot. I hope to counter Neoliberalism’s stature with a new story.

—

Why is this time different?

Before we tell a different story for our future, we have to consider the present. Currently, micro actors have leveled the playing field of disproportionate reach that macrostate actors had a monopoly on forever. As Moises Naim puts it, “In the 21st century, power is easier to get, harder to use, and easier to lose.”

Our current situation is unprecedented, says Latour, “No human society, however wise, subtle, prudent, and cautious you may think it to be, has had to grapple with the reactions of the earth system to the actions of 8 or 9 billion humans. All the wisdom accumulated over ten thousand years, even if we were to succeed in rediscovering it, has never served more than a few hundred, a few thousand, a few million human beings on a relatively stable stage.”

Most Americans would say that democracy will fix all of our ails, but two social science professors in their book, Democracy for Realists, argue that our images of the political spheres are at most not true, and at worst not possible. “The Folk Theory of Democracy - the idea that citizens make coherent and intelligible policy decisions, on which governments then act, bears no relationship to how democracy really works, or could ever work,” says Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels.

This ‘folk theory of democracy’ sets its foundation on the notion of rational choice. Basically we seek out information, weigh the pros and cons, and then elect a government that reflects those policies. But, in reality, the process is much more complicated in today’s age.

“In reality, the research they use suggest[s], most people possess almost no useful information about policies and their implications, have little desire to improve their state of knowledge and have a deep aversion to political disagreement,” echoes Monbiot.

This has become even more of an issue with the rise of technology in almost everything we do. Schwab says “With growing citizen empowerment and greater fragmentation and polarization of populations, this could result in political systems that make government more difficult and governments less effective. This is particularly important as it occurs at a time when governments should be essential partners in shaping the transition to new scientific, technological, economic, and societal frameworks.”

The climate emergency, the pervasiveness of artificial intelligence, and the rise of genetic engineering are all issues that nation-states are not capable of dealing with alone. The challenge for governments during this unique time is letting innovation flourish while minimizing risk.

“Two conceptual approaches exist. In the first, everything that is not explicitly forbidden is allowed. In the second, everything that is not explicitly allowed is forbidden. Governments must blend these approaches. They have to learn to collaborate and adapt while ensuring that the human being remains at the center of all decisions,” says Schwab.”

Rather than what we think, we base our political decisions on who we are. Politics is an expression of social identity, so we cannot change politics without changing social identities.

We are in need of a complete rearrangement of how citizens and government think and act toward each other, “To achieve this, governments will need to engage citizens more effectively and conduct policy experiments that allow for learning and adaptation. Both of these tasks mean that government and citizens alike must rethink their respective roles and how they interact with one another, simultaneously raising expectations to explicitly acknowledge the need to incorporate multiple perspectives and allow for failure and missteps along the way.”

—

Getting back Down to Earth

Bruno Latour’s book Down to Earth is the single best political theory book I have read that deals with Humans living in the Anthropocene. We are in a time of deep political division, but are in desperate need of political guidance. We need to look in a different a-priori direction that takes the climate “situation” seriously, and thus rearrange our outlook and subsequent policies.

Who would be in charge or who would have the ultimate authority in this new politics? That is always the first question. It is a valid question, but I am not here to answer it. I will offer a thought experiment on what type of system would constitute the foundation of what/who gives our supposed “authority” that level of gravitas. See if you can spot the difference below, and think about the possible radical implications of changing.

There are two types of systems that could be deployed, a system of production - freedom principle, humanity-centered role, mechanism type of movement; or a system of engendering - dependency principle, humanity’s role distributed, genesis type of movement.

A system of production: “based on a certain conception of nature, materialism, and the role of the sciences; it assigned a different function to politics and was rooted in a division between human actors and their resources. At bottom, there was the idea that human freedom would be deployed in a natural setting where it would be possible to indicate the precise limits of each property.”

OR

A system of engendering: “brings into confrontation agents, actors, animate beings that all have distinct capacities for reacting. It does not proceed from the same conception of materiality as the system of production, it does not have the same epistemology, and it does not lead to the same form of politics. It is not interested in producing goods, for humans, on the basis of resources, but in engendering terrestrials - not just humans, but all terrestrials. It is based on the idea of cultivating attachments, operations that are all the more difficult because animate beings are not limited by frontiers and are constantly overlapping, embedding themselves within one another.”

We already know the failings that a system of production would garner, but what kind of politics would a system of engendering have?

If you were to try to explain our political systems to a Martian, who had the knowledge of “the overview effect”, would you be able to?

I would use my lifeline, and call Bruno Latour.

—

De-familiarizing like a Martian

If you want to study humanity as a whole, famous linguist Noam Chomsky posed the thought experiment about trying to explain our world to a “Martian visiting Earth.” (Richard Feynman also talked about the importance of seeing the world anew, or like a Martian.)

“The Martian might notice things about us that we do not notice about ourselves, like seeing a unified human language structure rather than a set of many different languages. The Martian might be puzzled when you tried to explain what a nation-state was and why it mattered, or why we use chromosomal sex as an important category for classifying human beings, or why we have cars. “This kind of “defamiliarization”—trying to see things we take for granted as if you are seeing them for the first time—is very powerful at generating creative insights,” says Current Affairs founder and editor in chief Nathan Robinson.

He also says that seeing our present reality through the lens of deep time (thinking in the long now) will most likely cause a reevaluation of our priorities, “My friend Albert Kim says he has a much better understanding of politics whenever he tries to imagine our own society as if he is a teenager reading about it in a history book, 2000 years in the future. How does, for example, the greater attention paid to Trump and Ukraine over climate change look to students two millennia from now?”

We talked about Neoliberalism's rise and subsequent success as a silent but ever-present ideology. Latour says this has made us completely confused as to what is important, “We must face up to what is literally a problem of dimension, scale, and lodging: the planet is much too narrow and limited for globalization; at the same time, it is too big, infinitely too large, too active, and too complex to remain within the narrow and limited borders of any locality whatsoever. We are all overwhelmed twice over: by what is too big, and by what is too small.”

George Scialabba, in his book The Modern Predicament - Essays and Reviews, praises Morris Berman for illuminating our drive to make decisions; “The relentless American habit of choosing the individual solution over the collective one,” Berman writes, underlies “the design of our cities, including the rise of car culture, the growth of suburbs, and the nature of our architecture, [which] has had an overwhelming impact on the life of the nation as a whole, reflecting back on all the issues discussed here: work, children, media, community, economy, technology, globalization, and, especially, US foreign policy. The physical arrangements of our lives mirror the spiritual ones.”

—

Out of this World

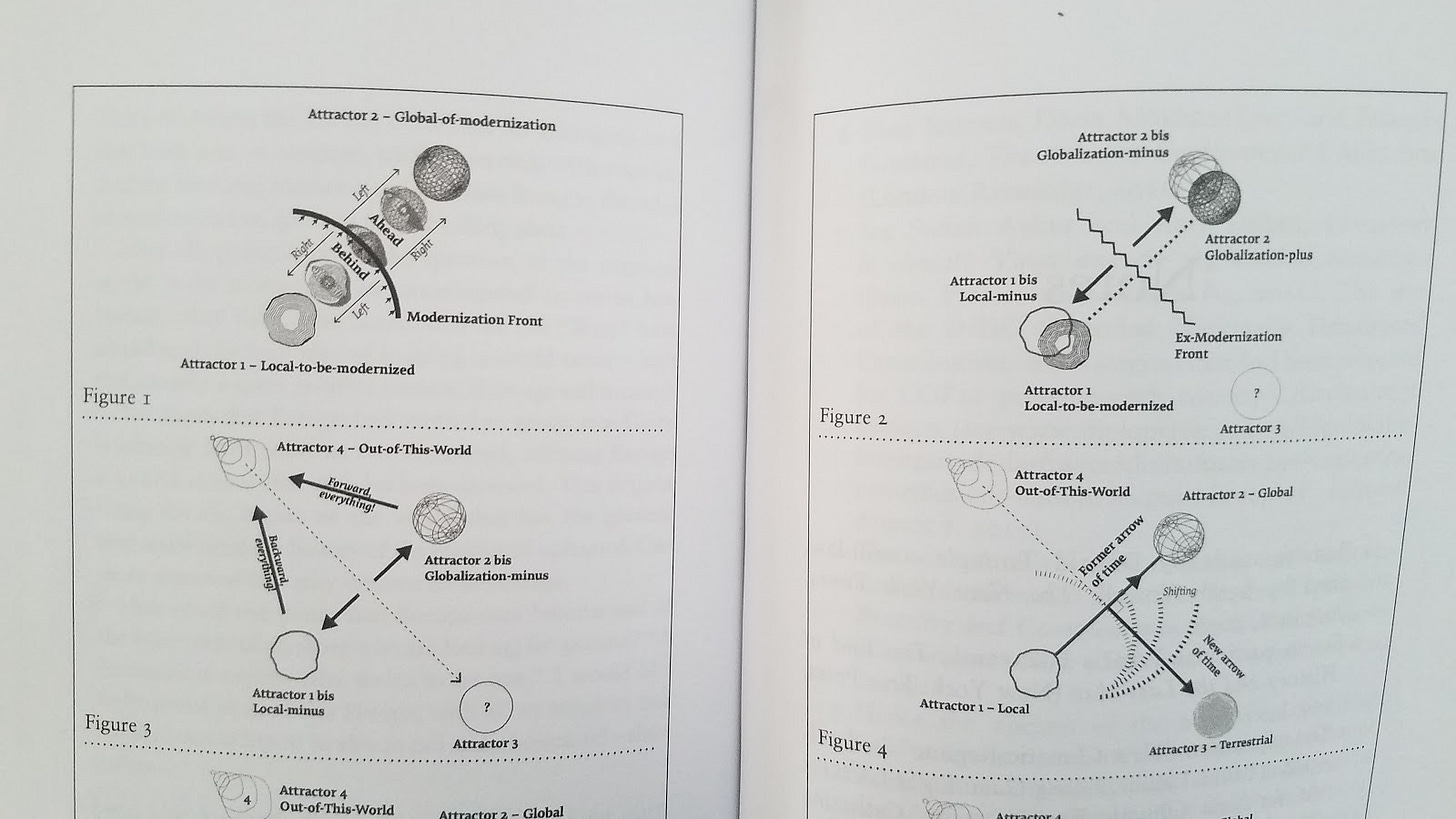

Throughout history, the local was always moving toward the global through modernization. People were torn between two contradictory statements: to move forward toward the ideal of progress (Global), or backward toward the old certainties (Local). A third option (Attractor 3) was skipped over as not possible, not efficient, or profitable, so a fourth option (Attractor 4) became the frontrunner and championed by people at the top of decision making who basically have given up in sharing the world with everyone else.

“These people - whom we can call the obscurantist elites from now on - understood that, if they wanted to survive in comfort, they had to stop pretending, even in their dreams, to share the Earth with the rest of the world,” says Latour.

This decision to orient toward “Out of This World” policies has had far-reaching effects on our global society, as elites started doing the simple calculation of how long they would have resources (and how many resources) to selfishly gobble up. When that calculation equated many more Earths than we have, they went full scorched earth for everyone except themselves. This is basically the plot of Elysium by the way, so our present reality is stranger than fiction...

“If the hypothesis is correct, all this is part of a single phenomenon: the elites have been so thoroughly convinced that there would be no future life for everyone that they have decided to get rid of all the burdens of solidarity as fast as possible - hence deregulation; they have decided that a sort of gilded fortress would have to be build for those (a small percentage) who would be able to make it through; and they have decided that to conceal the crass selfishness of such a flight out of the shared world, they would have to reject absolutely the threat at the origin of this headlong flight - hence the denial of climate change,” says Latour.

As Julius Krein writes in American Affairs, what is surprising about today’s oligarchy is its pettiness and purposelessness, not its ruthlessness. “An all-consuming megalomania might at least produce some great art as a side-effect. But this collection of mediocrities cannot even do that. Their political activities—whether pushing for a slightly lower tax rate or throwing money at a self-serving brand of faux progressivism—are too small-minded to be anything other than embarrassing. This class has no idea what to do with its wealth, much less the power that results from it. It can only withdraw and extract, socially and economically, while the political justifications for its existence melt away,” says Krein.

In Why We Can’t Afford the Rich, Andrew Sayer says that our idiot, yet powerful, elites confuse wealth extraction with wealth creation: “investment means two quite different things. One is the funding of productive and socially useful activities, the other is the purchase of existing assets to milk them for rent, interest, dividends, and capital gains.”

Which one have you met more of lately? I for one have seen a lot of the second, and not much of the first. But the ultimate question is will this continue.

Krein says if it does it will be deeply paradoxical to historians, “Ultimately, the question that will determine the future of American politics is whether the rest of the elite will consent to their continued proletarianization only to further enrich this pathetic oligarchy. If they do, future historians of American collapse will find something truly exceptional: capitalism without competence and feudalism without nobility.”

—

Attractor 3 or “The Terrestrial”

Latour expresses a current viewpoint of where Humanity is in the Anthropocene, “and it is at this point in history, at this juncture, that we find ourselves today. Too disoriented to array the positions along the axis that went from the old to the new, from the Local to the Global, but still incapable of naming this third attractor, fixing its position, or even simply describing it. And yet, the entire political orientation depends on this step to the side: we shall really have to decide who is helping us and who is betraying us, who is our friend and who is our enemy, with whom we should make alliances and with whom we should fight - but while taking a direction that is no longer mapped out.”

We have seen that through our collective modernization push from the local to the global, society only had two choices - to continue to progress or to fall back on the ancient ways. Obscurantist elites and the political powers that be decided there was another option (Attractor 4), one which mixed elements of what their parties had once believed and what their opponents believed. This “Out of this World” policy structure was not dealing in the reality of Humanity living through the Anthropocene or only having one Earth for everyone’s production and consumption metrics. Yet, if we were to tally how many Earths we would need for everyone to live like elites it would be more than one, which is a bit of a problem...

So what would the opposite of “Out of this World” look like? Bruno Latour’s central claim in Down to Earth is that it is not only possible for us to reorient our entire global political structure but it quite literally may be the only way we get to a society resembling the values we espouse into 2020 and beyond.

Reassessing the “Terrestrial” as the main political actor of our time would have immediate trickle-down effects everywhere on Earth. The question is whether the emergence and description of the Terrestrial attractor can give meaning and direction to political action. It does this in a very unique way by stating, “Existing as a people and being able to describe one’s dwelling place is one and the same thing.”

This configuration will traverse all scales of space and time, as being able to accurately define a terrestrial dwelling place will be step one in our process of making it our third attractor. Latour goes on, “to define a dwelling place, for a terrestrial, it to list what it needs for its subsistence, and, consequently, what it is ready to defend, with its own life if need be. This holds as true for a wolf as for a bacterium, for a business enterprise as for a forest, for a divinity as for a family…The challenge obviously lies in drawing up such a list…In a system of production, the list is easy to make: it consists of humans and resources. In a system of engendering, the task is much more difficult, because the animate beings, the actors that compose it all have their own trajectories and interests.”

Critics will say such a redescription of all terrestrial dwelling places is impossible, it is meaningless, and it has never been done. Well, they are wrong on all three accounts - nothing is impossible or meaningless, and Latour gives an example of how it was done before in France, albeit many years ago and in a small subset. This is no reason to stop or to throw our hands up and accept the “Out of this World” status quo we currently are experiencing. Plus, we have technology that could be used in conjunction with our new and different philosophical basis.

Latour says when we ask this type of question about terrestrial dwelling places we notice our own ignorance: “Every time one begins such an investigation, one is surprised by the abstract nature of the responses. And yet questions about engendering turn up everywhere, along with those of gender, race, education, food, jobs, technological innovations, religion, or leisure. But here is the problem: globalization-minus has made us lose sight, in the literal sense, of the cause of effects of our subjections. Hence the temptation to complain in general, and the impression of no longer having any leverage that could enable us to modify the situation.”

—

Out of the wreckage by telling a different story

To create the leverage that could enable us to modify the situation, we need to rethink our “why.” If our current political theories only promote alienation in the end, then we need their antithesis. And, if alienation is the point where all our current crises merge, belonging is the means by which we can address them. Yes - BELONGING.

Three forms of belonging exist say philosopher Kimberley Brownlee: belonging with, belonging to, and belonging in. The first deals with symmetry and reciprocity such as “we go together, love and marriage, horse and carriage.” The second deals with exercising power or ownership over, but could also describe a child. The last deals with how at-peace we feel in social settings or surroundings.

Monbiot says the way out of the wreckage is through thick networks of engaged citizens, “the most plausible candidate is the local community, formed around participatory culture, building outwards to revive national and global politics.”

—

Community

Instead of making the workplace the primary focus of our political lives, we make it about community! “The problem with using work as a reference point for identity is that desirable identities become exclusive and hard to obtain. No such problem surrounds a sense of identity and validity arising from active citizenship. Anyone can join; anyone can make a contribution. Anyone can come to see themselves as a person who builds community, and who is responsible for others’ well-being. There are no losers anymore,” says Monbiot.

This approach has four virtues:

“No part of the process is wasted. “We didn’t take power” isn't a death knell for progress.

Most steps toward change are pleasant, not dependent on political meetings

The process of change is open to everyone, not just those employed in particular industries.

You do not need to wait for anyone else’s permission to begin.”

Monbiot warns that this is NOT a political panacea, “It does not cure the explorations of the workplace or the attempts by some people to grab political power by undemocratic means or assets such as physical space and public budgets from being captured for the exclusive use of the few.”

—

Subsidiarity

Economics is a key feature of Terrestrial politics, but we will wait until our last essay in the E-Book to dive into that as a future way out of Four Economic Futures. Monbiot champions Doughnut Economics, participatory budgeting, and increasing each citizen’s feeling of owning the system. But the most important feature, Monbiot says of a politics of belonging and community, should be “powers & responsibility are handed to the smallest political unit that can reasonably discharge them. This principle, known as subsidiarity, is widely accepted in theory, but seldom deployed in practice.”

The hardest questions of our times are too important to be left to economists alone, but the answers should belong to each and every Terrestrial. “Democratic power should be grounded in actual choice and consent, rather than in the imagined permission that political systems presumptuously grant themselves,” says Monbiot.

Constitutional conventions, sortition - or choosing most delegates by lot, and proportional representation all make cameos in how we could achieve real democratic power. Monbiot proposes a “directly elected world parliament” that would oversee all institutions and hold them accountable because “global bodies have no more right than any other to operate without explicit public consent.” There are two possible responses to the power shift at the global level; to seek to repatriate it or to seek to democratize it. Global governance is NOT the same as a global government.

Klaus, Latour, Monbiot, and Scialabba seem to be doing the most they can to further the latter. Maybe not specifically “global democracy” - whatever that might be - but they are trying to democratize the power that each individual being or Terrestrial has for itself.

In closing, Scialabba echoes Barbara Ehrenreich in how solidarity is of the greatest importance for all Terrestrials moving into the future,

“Nothing in history or human nature guarantees that we will avoid social stasis, environmental collapse, or nuclear catastrophe. Our danger is not positive error so much as sheer unreflectiveness; not active malevolence so much as paralyzing insecurity. Habits of the Heart is a slight enough blow against modern anomie, as is Fear of Falling against class divisions. But their convergence, however partial and implicit, is encouraging. Because probably, if there is to be any ground for hope, the first requirement is the solidarity of the hopeful: communitarian and individualist, republican and socialist, religious and secular.”

Audio—

“Out of the Wreckage: A new politics for an age of crisis” Audiobook

Bruno Latour and Dipesh Chakrabarty: Geopolitics and the “Facts” of Climate Change

Partially Examined Life Ep. 230: Bruno Latour on Science, Culture, and Modernity (Part One)

Partially Examined Life Ep. 231: Bruno Latour on Science, Culture, and Modernity (Part Two)

Video Playlist—

1) Actor-Network Theory: Primer

2) Neoliberalism is dead: we need a new political story - George Monbiot

3) Society – Technology – People: Interview with Prof. Bruno Latour

4) Bruno Latour: Why Gaia is not the Globe

5) Bruno Latour | On Not Joining the Dots || Radcliffe Institute

6) Senior Loeb Scholar Lecture: Bruno Latour, “A Tale of Seven Planets – An Exercise in Gaiapolitics”

7) George Monbiot - Out of the Wreckage - A New Politics for an Age of Crisis - The Gaia Foundation

8) George Monbiot: Out of the Wreckage - The Majority Report w/Sam Seder Live - 9/13/17

What’s Next?

The next newsletter will be on: Four Future of Economics

If you enjoyed this post, please share with other potential eclectic spacewalkers, consider subscribing or gift a subscription, or connect with us on social media to continue the conversation! Also, I am an advocate of Bitcoin. My address is on my About.Me page if you are feeling extra curious.

Subscribe to Substack Newsletter

Listen to all podcasts on Anchor

Follow Eclectic Spacewalk on Twitter

Thank You for your time. Until the next post, Ad Astra!