Eclectic Spacewalk #2 - Systems Thinking

Summary of Systems Principles, 12 Places to Intervene, 15 Guidelines for Living in a World of Systems

Read previous post #1 - The “Overview Effect” (15-20min read)

Table of Contents:

Systems Thinking—

Summary of Systems Principles

12 Places to Intervene in a System (In increasing order of effectiveness)

15 Guidelines for living in a world of systems

Text

Audio

Video

Websites & Groups

What’s Next?

Reading Time: 25-30 minutes (Read sections you find intriguing, bookmark the media/links, and come back to anytime.")

Systems Thinking—

Abstract: “The holistic approach to analysis that focuses on the way a system's constituent parts interrelate, and how systems work over time and within the context of larger systems.”

I am a system and a complex one at that. You are a complex system as well, dear reader. I am going to pose a very straightforward and simple question: What else is a system? Although it will sound hyperbolic, my answer would be just about everything in reality.

In this essay, I will talk about Systems Thinking and I hope, by the end, you will begin to see the world through a systems-principles lens moving forward. You see and interact with untold numbers of conscious and unconscious systems every day. Your body is a system, including your intestines, capillaries, and brain. Your cat’s body is too. The interstates are aptly called the “highway system.” Your country is a system, along with its culture. Any electronics are systems. The Dutch East India Trading Company was a system. Government, Economics, Education are all systems. Whether your laundry pile is a system is debatable, however. What do you think?

Two “thought” primers before we get into the material: Scale and Modeling.

Let’s start with scale. Where are my Men In Black fans? In the movie is a scene where the camera zooms out from NYC through the atmosphere, past the outside of our solar system, then past the Milky Way galaxy, to you seeing that our entire universe is a little marble used by another creature/alien playing a game on a truly incomprehensible scale.

Let’s begin with the biggest system we know of: The Universe. The system elements of the entire universe would obviously include the “observable” universe but also the not-so-obvious “non-observable” universe (farther than telescopes can see). Also, to really wrap your head around systems thinking, be dumbfounded by the fact that our entire universe MAY be only PART of an infinitely larger “Many Worlds Theory” Universe.

I bring this up to open your mind to the inevitable conclusion that there are different systems at almost every level of reality, all crisscrossing at different proportions and with varying degrees of influence. Here is the best visualization of the scale of our universe. (Disclaimer: You might want to sit down if you aren’t already because it is quite mind-boggling for our proto-conscious human brain to wrap our heads around, if at all, in any meaningful way.)

What is the smallest system we know of? The answer has become more accurate over time. It used to be a cell. Then it was the atom. Then it was quarks - the subatomic particles that make up atoms. Now it is the Planck Length. But that may just be the threshold of our current knowledge and may change, or may not...

We have no idea how far the universe *really* goes in either direction of the spectrum, large-scale universe size, or the small-scale quantum level.

The second primer has to deal with Models--almost all mental models. I have to remind you that “everything we think we know about the world is a model.” This idea was brilliantly captured when Bryan Magee interviewed Noam Chomsky:

“Each one of us forms a systematically distorted view of the world because it's all built upon what accidentally happens to be the particular & really rather narrow experience of the individual who does it. Now do you think that something of that kind applies to man as a whole because of the reasons implicit in your theory? That is to say that the whole picture that mankind has formed of the cosmos of the universe of the world must be systematically distorted and what's more drastically limited by the nature of the particular apparatus for understanding that he happens to have.” -

Depending on your perspective, this can be viewed as:

Less potential in pursuit of never attaining perfectionism in “our models fall far short of representing the real world fully.”

Or, sheer awe in the ability to shape your/our environment in “our models do have a strong congruence with the world.”

—

Summary of System Principles

Almost all of the information discussed in this essay comes from Donella M. Meadows’s magnum opus “Thinking In Systems: A Primer.” (We also pull from Daniel Kim’s Introduction to Systems Thinking PDF and other sources listed within the links). Both are exquisite in their deft layman’s explanation of a system, its behavior, and its view of ‘Thinking in Systems.’ Meadows’s primer has numerous illustrations and graphs to pair with the simple text. Words like stocks, flows, equilibrium, and feedback loops are usual terms known to the casual reader, but the book goes deeper with definitions and examples of resilience, self-organization, hierarchy, shifting dominance, delays, and oscillations. Not only does the author offer a thoughtful view of all the components of the system, but also provides pithy responses to system traps with real-world examples!

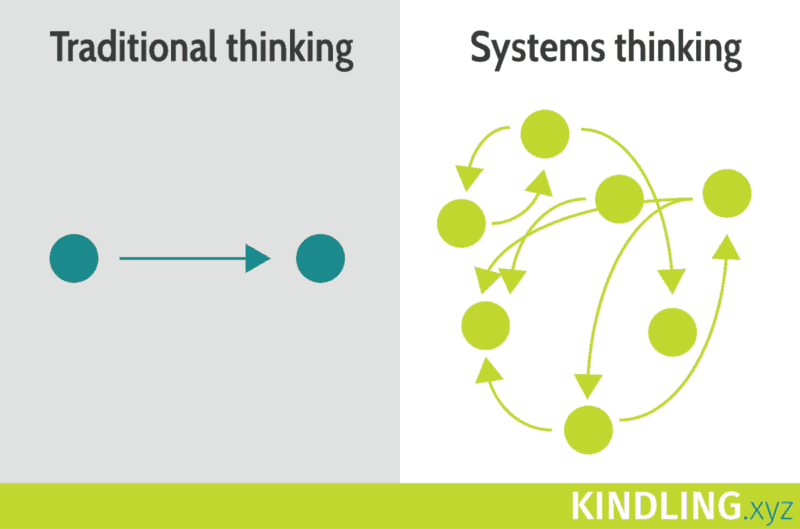

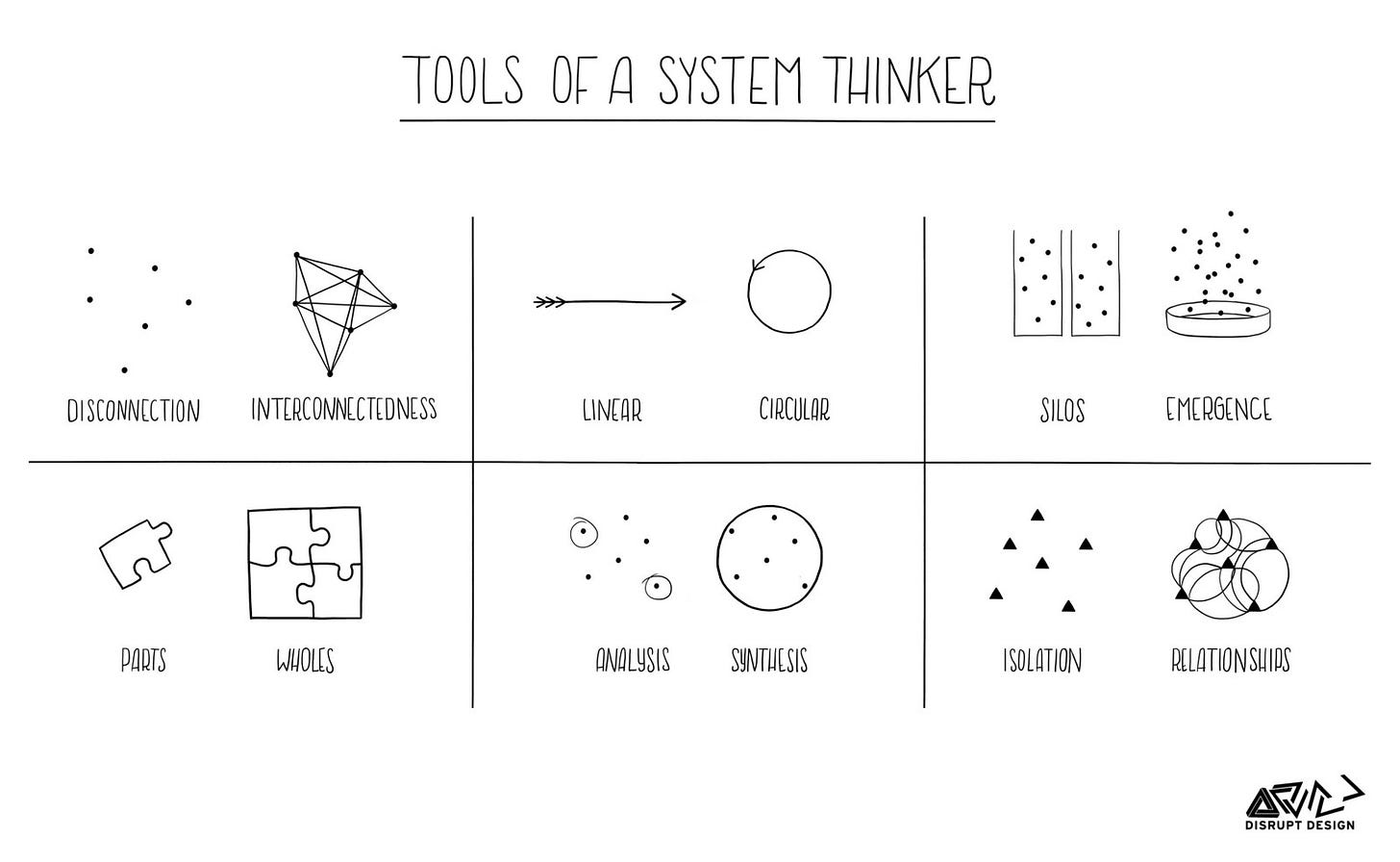

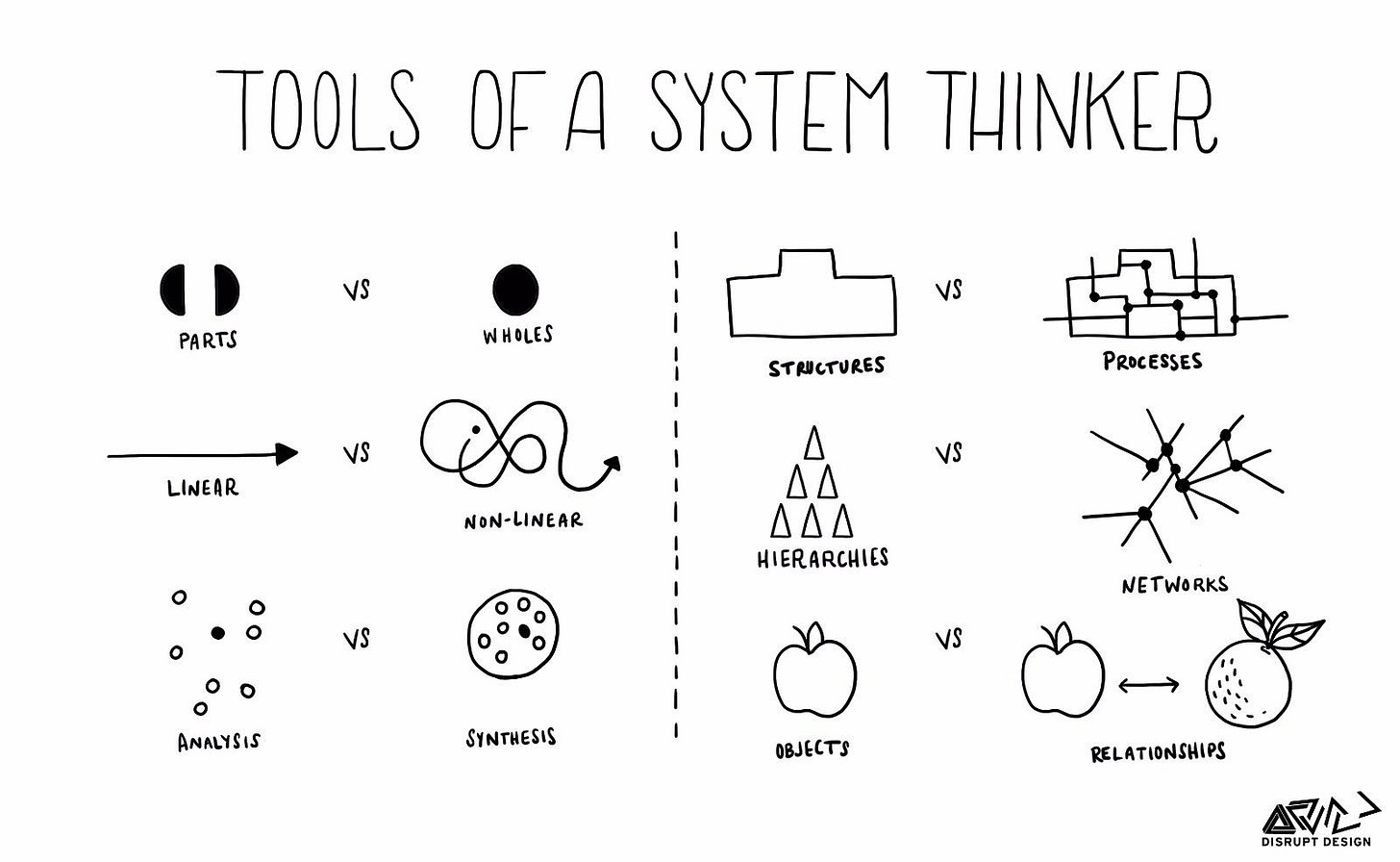

We are specifically focusing on systems thinking, “as in the holistic approach to analysis that focuses on the way that a system's constituent parts interrelate and how systems work over time and within the context of larger systems. The systems-thinking approach contrasts with traditional analysis, which studies systems by breaking them down into their separate elements.” With biology, cybernetics, and ecology as its roots, systems thinking “provides a way of looking at how the world works that differs markedly from the traditional reductionistic, analytic view.”

As we continue on our systems-thinking journey, let’s remember:

A system is more than the sum of its parts.

Many of the interconnections in systems operate through the flow of information.

The least obvious part of the system, its function or purpose, is often the most crucial determinant of the system’s behavior.

System structure is the source of system behavior. System behavior reveals itself as a series of events over time.

The sources of system surprises (or challenges) come in many shapes, sizes, but in the end are always connected. Some are quite counterintuitive, actually.

Many relationships in systems are nonlinear.

There are no separate systems. The world is a continuum. Where to draw a boundary around a system depends on the purpose of the discussion.

At any given time, the input that is most important to a system is the one that is most limiting.

Any physical entity with multiple inputs and outputs is surrounded by layers of limits.

There always will be limits of growth.

A quantity growing exponentially toward a limit reaches that limit in a surprisingly short time.

Where there are long delays in feedback loops, some sort of foresight is essential.

The bounded rationality of each actor in a system may not lead to decisions that further the welfare of the system as a whole.

—

Places to Intervene in a System

(In increasing order of effectiveness)

With a cursory knowledge of system principles, the next issue is how to “change the structure of the systems to produce more of what we want and less of that which is undesirable?” Bonus points for answering in increasing order of effectiveness.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Jay Forrester likes to say that the average manager can define the current problem very cogently: “identify the system structure that leads to the problem, and guess with great accuracy where to look for leverage points - places in the system where a small change could lead to a large shift in behavior.”

LEVERAGE POINTS ARE POINTS OF POWER.

“The idea of leverage points is not unique to systems analysis - it’s embedded in legend: the silver bullet; the trim tab; the miracle cure; the secret passage; the magic password; the single hero who turns the tide of history; the nearly effortless way to cut through or leap over huge obstacles,” says Forrester.

“Although people deeply involved in a system often know intuitively where to find leverage points, more often than not they push the change in the WRONG DIRECTION.’

Forrester was asked by Club of Rome to create a world model, and after much deliberation about what kind of model to use he made a computer model. The results came with a clear leverage point: GROWTH. “Not only population growth, but economic growth. Growth has costs as well as benefits, and we typically don’t count the costs - among which are poverty and hunger, environmental destruction, and so on - the whole list of problems we are trying to solve with growth!”

Forrester tells us the solution, “What is needed is much slower, very different kinds of growth, and in some cases no growth or negative growth.”

“The world’s leaders are correctly fixated on economic growth as the answer to virtually all problems, but they’re pushing with all their might in the wrong direction,” challenges Forrester.

COUNTERINTUITIVE - is Forrester’s word to describe complex systems. Leverage points frequently are not intuitive.

In increasing order of effectiveness

12. Numbers: Constants and parameters such as subsidies, taxes, and standards

11. Buffers: The sizes of stabilizing stocks relative to their flows.

10. Stock-and-Flow Structures: Physical systems and their nodes of intersection

9. Delays: The lengths of time relative to the rates of system changes

8. Balancing Feedback Loops: The strength of the feedbacks relative to the impacts they are trying to correct.

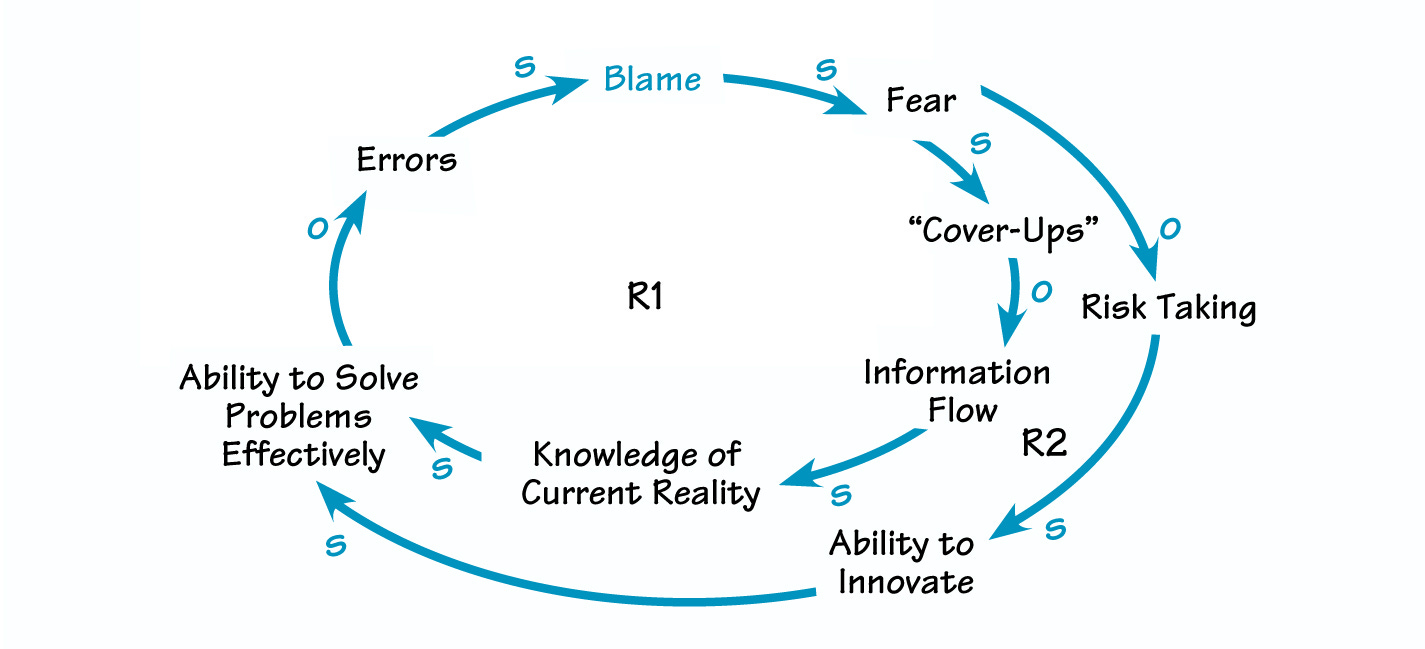

7. Reinforcing Feedback Loops: The strength of the gain of driving loops

6. Information Flows: The structure of who does and does not have access to information

5. Rules: Incentives, punishments, constraints

4. Self-Organization: The power to add, change, or evolve system structure

3. Goals: The purpose of the system

2. Paradigms: The mind-set out of which the system - its goals, structure, rules, delays, parameters - arises

1.Transcending Paradigms: No paradigm is “true.”

—

15 Guidelines for Living in a World of Systems

Cultural Thinking patterns, and thus you and each reader’s cultural and personal thinking, are the sum total of all human needs, strengths & weaknesses, and emotions externally manifesting as a “social system.” One might think that there could be some “end” of the road, such as a complete understanding of a system, but real system insight would continue to raise even more questions.

The curious among us have been at this crossroads for some time. When we started asking systems-thinking-inspired questions, we founded disciplines, libraries, histories, and other stores of knowledge to continue on our social quest of knowledge of ourselves and the environment.

“Systems thinking makes clear even to the most committed technocrat that getting along in this world of complex systems requires more than technocracy.”

“Self-organizing, non-linear, feedback systems are inherently unpredictable. They are not controllable. They are understandable only in the most general way.”

Living in a World of Systems through 15 Guidelines

Get the beat of the system

Observe first before thinking or acting, and learn system history. “Before you disturb the system in any way, watch how it behaves...Learn its history,” says Meadows. She goes on, “This guideline is deceptively simple. Making it a practice, you won’t believe how many wrong turns it helps you avoid. Starting with the behavior of the system forces you to focus on facts, not theories. It keeps you from falling too quickly into your own beliefs or misconceptions, or those of others.” The first thing to do is, “Watching what really happens, instead of listening to people’s theories of what happens, can explode many careless causal hypotheses.”

Meadows wants us to pay attention to the system’s interconnected history, “Starting with the behavior of the system directs one’s thoughts to dynamic, not static, analysis…the history of several variables plotted together begins to suggest not only what elements are in the system, but how they might be interconnected.” Questions like “What's wrong?” turns into ‘How did we get there? What other behavior modes are possible? If we don’t change direction, where are we going to end up?”’

“Discourages the common distracting tendency we all have to define a problem not by the system’s actual behavior, but by the lack of our favorite solution,” says Meadows. The key is to pay attention to the what and why of a system, “Listen to any discussion and watch people leap to solutions, usually solutions in “predict, control, or impose your will” mode, without having paid any attention to what the system is doing and why.”

If we want to affect change within a system especially, in today’s world, we have to ‘Decenter from Technology’ in general. “Nuanced historical context of the discrimination to which automated systems belongs will also add much needed texture to the abstract computational models. Without this, challenging technologically mediated discrimination risks insularity at a time when a just society demands greater interconnection and alignment between diverse epistemic communities,” says Meadows.

Expose your mental models to the light of day.

We all need to make our assumptions visible and express them with rigor. “We have to put every one of our assumptions about the system out where others (and we ourselves) can see them. Our models have to be complete, and they have to add up, and they have to be consistent. Our assumptions can no longer slide around (mental models are very slippery), assuming one thing for purposes of one discussion and something else contradictory for purposes of the next discussion,“ says Meadows. An example would be evangelical Christians preaching a pro-life message for abortions, but not for death row inmates.

Your mental model doesn’t have to comprise diagrams and equations, even though doing so is good practice. Meadows says thinking spatially makes you more flexible to learn, “Words, lists, pictures, or arrows showing how things are connected to what. The more you do that, in any form, the clearer your thinking will become, the faster you will admit your uncertainties, and correct your mistakes, and the more flexible you will learn to be.” She goes on, “Mental flexibility - the willingness to redraw boundaries, to notice that a system has shifted into a new mode, to see how to redesign structure - is a necessity when you live in a world with flexible systems.”

“Remember, always, that everything you know, and everything everyone knows, is only a model,” exclaims Meadows. Get your own identity out of the way, “Instead of becoming a champion for one possible explanation or hypothesis or model, collect as many as possible. Consider all of them to be plausible until you find some evidence that cause[s] you to rule one out. That way you will be emotionally able to see the evidence that rules out an assumption that may become entangled with your own identity.”

Meadows echoes how exposing your mental models to the light is literally the scientific method, “Getting models out into the light of day, making them as rigorous as possible, testing them against the evidence, and [being] willing to scuttle them if they are longer supported is nothing more than practicing the scientific method - something done too seldom in science, and done hardly at all in social science or management or government or everyday life.”Your mental model doesn’t have to be diagrams and equations, even though doing so is good practice.

Honor, respect, and distribute information.

“Information holds systems together and how delayed, biased, scattered, or missing information can make feedback loops malfunction,” explains Meadows.

Time is of the essence! “Decision-makers can’t respond to information they don’t have, can't respond accurately to information that is inaccurate, and can’t respond in a timely way to information that is late,” exclaims Meadows, “I would guess that most of what goes wrong in systems goes wrong because of biased, late, or missing information.”

One example of releasing previously withheld information Meadows uses is The Toxic Release Inventory legislation of 1986. It confirmed its own worth and then some. Within two years of its release emissions had decreased by 40 percent.

“The Toxic Release Inventory legislation of 1986 required companies to report all hazardous air pollutants emitted from their factories each year. Because of that legislation and the FOIA, the first data became available to the public. No Lawsuits, no required reductions, no fines, no penalties.”

Information is power alludes Meadows, “Anyone interested in power grasps that idea very quickly. The media, the public relations people, the politicians, and advertisers who regulate much of the public flow of information have far more power than most people realize. THEY FILTER AND CHANNEL INFORMATION. Often they do so for short-term, self-interested purposes. It’s no wonder that our social system so often runs amok.”

Use language with care and enrich it with systems concepts.

“Our information streams are composed primarily of language. Our mental models are mostly verbal,” says Meadows.

Fred Kofman wrote of language’s bedrock status in human’s understanding of systems, “Language can serve as a medium through which we create new understandings and new realities as we begin to talk about them. In fact, we don’t talk about what we see; we see only what we can talk about. Our perspectives on the world depend on the interaction of our nervous system and our language - both act as filters through which we perceive our world.

The language and information systems of an organization are not an objective means of describing an outside reality - they fundamentally structure the perception and actions of its members. To reshape the measurement and communication systems of a society is to reshape all potential interactions at the most fundamental level. Language...as articulation of reality is more primordial than strategy, structure, or...culture.”

“If society talks incessantly about productivity but doesn't understand the word resilience or its use then the society will be productive and not resilient. If we don’t understand carrying capacity then we will exceed our carrying capacity,” says Meadows.

A society that talks about a “peacekeeper” missile or “collateral damage,” a “final solution,” or “ethnic cleansing” is speaking tyrannese.

Wendell Berry explains: “My impression is that we have seen, for perhaps a hundred and fifty years, a gradual increase in language that is either meaningless or destructive of meaning. And I believe that this increasing unreliability of language parallels the increasing disintegration, over the same period, of persons and communities...In this degenerative accounting, language is almost without the power of designation, because it is used conscientiously to refer to nothing in particular. Attention rests upon percentages, categories, abstract functions...It is not language that the user will very likely be required to stand by or to act on, for it does not define any personal ground for standing or acting. It's only practical utility is to support with “expert opinion” a vast, impersonal technological action already begun. It is a tyrannical language: tyrannese.”

Honoring language means, above all, avoiding language pollution - making the cleanest possible use we can of language. “The first step in respecting language is keeping it as concrete, meaningful, and truthful as possible - part of the job of keeping information streams clear,” says Meadows.

Second, it means expanding our language so we can talk about complexity. Word processing program spell check tools didn’t have words like feedback, through-put, overshoot, self-organization, and sustainability. (At least until 2008)

Pay attention to what is important, not just what is quantifiable.

Meadows states, “Our culture, obsessed with numbers, has given us the idea that what we can measure is more important than what we can’t measure.”

“Pretending that something doesn’t exist if it’s hard to quantify leads to faulty models. You already saw the system trap that comes from setting goals around what is easily measured rather than around what is important,” says Meadows.

Human beings can count, but also have the ability to access quality. So, be a quality detector!!!

“If something is ugly, say so. If it is tacky, inappropriate, out of proportion, unsustainable, morally degrading, ecologically impoverishing, or humanely demeaning, don’t let it pass. Don’t be stopped by the ‘if you can’t define it and measure it, I don’t have to pay attention to it’ ploy...

No one can define or measure justice, democracy, security, freedom, truth, or love. No one can define or measure any value. But if no one speaks up for them, if systems aren’t designed to produce them, if we don’t speak about them and point toward their presence or absence, they will cease to exist,” challenges Meadows.

Make feedback policies for feedback systems.

“What gets measured gets done, what gets measured and fed back gets done well, what gets rewarded gets repeated.” ~ John E. Jones

“A dynamic, self-adjusting feedback system cannot be governed by a static, unbending policy. It’s easier, more effective, and usually much cheaper to design policies that change depending on the state of the system,” says Meadows.

Using the system’s features will work in your favor, “Especially where there are great uncertainties, the best policies not only contain feedback loops, but meta-feedback loops - loops that alter, correct, and expand loops.”

Meadows uses the example of US President Jimmy Carter who tried twice and failed to institute feedback policies.

A tax on gasoline proportional to the fraction of US oil consumption that had to be imported.

“Instead of spending money on border guards and security, we should help build the Mexican economy, and do so until the immigration problem stopped.”

“These are policies that design learning into the management process,” states Meadows.

The Montreal Protocol is another example Meadows uses. “Signed in 1987, it provides no certainty about danger, rate at degrading, or specific effect of chemicals. The Protocol set rates clearly BUT ALSO required monitoring the situation and reconvening an international congress to change the phase-out schedule if needed. Three years later, they sped things up since the initial damage was greater than first thought. A structure for learning feedback policy.”

Go for the good of the whole.

Meadows challenges us to really think holistically, “Remember that hierarchies exist to serve the bottom layers, not the top. Don’t maximize parts of the systems or subsystems while ignoring the whole. Don’t, as Kenneth Boulding once said, go to great trouble to optimize something that never should be done at all. Aim to enhance total systems properties, such as growth, stability, diversity, resilience, and sustainability - whether they are easily measured or not.”

INVERT THE HIERARCHY PYRAMID!

Listen to the wisdom of the system.

Aid and encourage the forces and structures that help the system run itself. Many are at the bottom of the hierarchy. “Before you charge in to make things better, pay attention to the value of what’s already there,” says Meadows.

Aid agencies arrive and want to “create jobs,” and “attract outside investors,” and “increasing entrepreneurial spirit.” Aid agencies assert these goals, all the while walking right past thriving city centers, markets, and small-scale businesses literally doing everything above. No outside investors should be involved; instead, use inside ones. “Small loans available at reasonable interest rates, and classes in literacy and accounting, would produce much more long-term good for the community than bringing in a factory or assembly plan from outside,” exclaims Meadows.

Locate responsibility within the system. (Skin in the Game ‘esque)

A guideline for both analysis and design.

Analysis - How does the system create its own behavior? Paying attention to triggering events or outside forces that bring about one kind of behavior from the system rather than another. Meadows explains, “Intrinsic Responsibility means that the system is designed to send feedback about the consequences of decision making directly, quickly, and compellingly to the decision-makers.”

An example of this is how a pilot rides in the front of the plane, so he or she will directly experience the consequences of their actions. A comical example Meadows uses comes from academia and how temperature control decisions were left to a central computer to save money but caused overcorrecting and other headaches to deal with. A solution to this would be to have more than one option. Professors could have still been responsible for the temperature, but charge consumers directly for the amount of energy they use. (Watch the Borneo cats feedback loop story below in the Videos section.)

Design - Our current culture doesn’t look for responsibility within the system that generates an action. We design systems to NOT experience the consequences of their actions like a system that has Skin in the Game principles. Rulers who declared war were no longer leading troops in battle, and even more so with drone strikes and the distance between action and its consequences. “Garrett Hardin has suggested that people who want to prevent other people from having an abortion are not practicing intrinsic responsibility unless they are personally willing to bring up the resulting child,” questions Meadows.

Stay humble - stay a learner.

Structure your life in such a way that you are constantly reminded, as we should be, of how incomplete my/your/our mental models are, how complex the world is, and how much I/you/we don’t know. Learning is the only way. You learn through experiment. As Buckminster Fuller put it: “by trial and error, error, error.”

“‘Stay the course’ is only a good idea if you’re sure you’re on course!” says Meadows, “It’s hard. It means making mistakes and, worse, admitting them. It takes a lot of courage to embrace your errors.”

Psychologist Don Michael calls this “error-embracing...Distrust of institutions and authority figures is increasing. The very act of acknowledging uncertainty could help reverse this worsening trend.” Michael goes on, “Error-embracing is the condition for learning. It means seeking, using - and sharing - information about what went wrong and what you expected or hoped would go right. Both error embracing and living with high levels of uncertainty emphasize our personal as well as societal vulnerability. Typically we hide our vulnerabilities from ourselves as well as from others. But...to be the kind of person who truly accepts his responsibility...requires knowledge of and access to self far beyond that possessed by most people in this society.”

Celebrate complexity.

The reality is the universe is messy, non-linear, turbulent, dynamic, self-organizing, ever-evolving, creating diversity AND uniformity. This paradox makes the world interesting and beautiful. Humans also have a paradox to deal with. The mind is “attracted to straight lines and not curves, to whole numbers and not fractions, to uniformity and not diversity, and to certainties and not mystery.”

BUT we also have an opposite set of attractions constantly pulling at this apparent innateness with us being the product of complex feedback systems. We should celebrate and encourage self-organization, disorder, variety, and diversity. Aldo Leopold made a moral code out of it: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

Expand time horizons.

The longer the operant time horizon, the better the chances for survival. Interest rates are in the hall of fame of humanity’s worst ideas. It is a rational, quantitative excuse for ignoring the long term. Meadows implores us to think differently about time, “In a strict systems sense, there is no long-term or short-term distinction. Phenomena at different time-scales are nested within each other...Systems are always coupling and uncoupling the large and the small, the fast and the slow...You need to be watching both the short and the long term - the whole system.”

Defy disciplines.

Following the system anywhere it leads will be sure to lead you across traditional disciplinary lines. You will have to learn from the discipline, see-through its honest lens, but discard the distortions caused by its blinders. Meadows states, “Interdisciplinary communication works only if there is a real problem to be solved, and if the representatives from the various disciplines are more committed to solving the problem than to being academically correct. They will have to go into learning mode. They will have to admit ignorance and be willing to be taught, by each other and by the system. It can be done. It’s very exciting when it happens.”

Expand the boundary of caring.

If moral arguments are not sufficient in rigor for you, then systems thinking has pragmatic reasons to back morals. “The real system is interconnected. No part of the human race is separate either from human beings or from the global ecosystem,” says Meadows.

Don’t erode the goal of goodness.

Modern industrial culture has eroded the goal of morality. Bad human behavior is held up as typical and basically glorified by media and culture; this is expected since we are human. There are far more numerous examples of “goodness,” but they are exceptions of saintly behavior and can't expect everyone to do that. Literary critic and naturalist, Joseph Wood Krutch, puts it this way: “Thus though man has never before been so complacent about what he has, or so confident of his ability to do whatever he sets his mind upon, it is at the same time true that he never before accepted so low an estimate of what he is. That same scientific method which enabled him to create his wealth and to unleash the power he wields has, he believes, enabled biology and psychology to explain him away - or at least to explain away whatever used to seem unique or even in any way mysterious...Truly he is, for all his wealth and power, poor in spirit.”

Donella Meadows concludes with a pithy statement about systems thinking not being omnipotent, “System thinking can only tell us to do that. It can’t do it. We’re back to the gap between understanding and implementation. Systems thinking by itself cannot bridge that gap, but it can lead us to the edge of what analysis can do and then point beyond - to what can and must be done by the human spirit.”

—

Onward to the future with a systems-thinking worldview!

The future cannot be predicted, but it can be envisioned with foresight, critical thinking, and a holistic approach to any mental model. All we can do is commit to learning, designing, and - the most important part - redesigning with the knowledge and expertise of the previous design history. The world is full of surprises, and we have to learn from each one!

“We can’t control systems or figure them out. But we can dance with them!”

“Stay wide awake, pay close attention, participate flat out, and respond to feedback.”

“Living successfully in a world of systems requires more of us than our ability to calculate. It requires our full humanity - our rationality, our ability to sort truth from falsehood, our intuition, our compassion, our vision, and our morality.”

Text:

1) Thinking in Systems: A Primer

“Some of the biggest problems facing the world—war, hunger, poverty, and environmental degradation—are essentially system failures. They cannot be solved by fixing one piece in isolation from the others, because even seemingly minor details have enormous power to undermine the best efforts of too-narrow thinking…

In a world growing ever more complicated, crowded, and interdependent, Thinking in Systems helps readers avoid confusion and helplessness, the first step toward finding proactive and effective solutions.”

2) Introduction to Systems Thinking

“It’s been said that systems thinking is one of the key management competencies for the 21st century. As our world becomes ever more tightly interwoven globally and as the pace of change continues to increase, we will all need to become increasingly “system-wise.” This volume gives you the language and tools you need to start applying systems thinking principles and practices in your own organization.”

3) Top 15 books on Systems Thinking by DZone

“I created this list by finding suggestions on Systems Thinking groups (here, here and here), and some intensive searches on Amazon. The results are ranked by a combination of rating and popularity, both on Amazon and GoodReads. (For example, Peter M. Senge’s book is the most popular, but Donella Meadows book has better ratings both on Amazon and on GoodReads, which is why her book won the top slot.)”

4) A Systems Story key concepts PDF

Audio:

1) Systems Thinking for Social Change

“In this interview, Mr. Stroh offers practical advice on how systems thinking can, to echo his book’s subtitle, solve complex problems, avoid unintended consequences, and achieve lasting results. Listen to the full conversation on the player below, and/or scroll down to read a transcript provided by the Business of Giving.”

2) An Educator's Guide to Systems Thinking

“In this episode, Angie talks with systems educator and award-winning author, Linda Booth Sweeney. Booth Sweeney describes her work as a systems educator and explains why understanding systems is so important. She shares many wonderful examples and stories of patterns (and feedback loops) that show up in everyday life and explains how seeing a pattern is the very first step toward influencing change. Booth Sweeney also talks about her books and why storytelling is such an instrumental tool in her work.”

3) Systems Thinking Podcasts from PlayerFM

“Best Systems Thinking podcasts we could find (Updated July 2019)”

Video:

Playlist

1 - Systems Thinking

“A short video explaining the primary differences between analytical methods of reasoning and systems thinking while also discussing the two methods that underpin them; synthesis and reductionism.” - Systems Academy

2) Systems thinking: a cautionary tale (cats in Borneo)

“This video about systems thinking tells the story of "Operation Cat Drop" that occurred in Borneo in the 1950's. It is a reminder that when solutions are implemented without a systems perspective they often create new problems.”

3) Systems-thinking: A Little Film About a Big Idea

“Our Mission-Vision is to Engage, Educate, and Empower 7 Billion Systems Thinkers to solve everyday and wicked problems.”- Cabrera Research Lab

4) TEDxDirigo - Eli Stefanski - Making Systems Thinking Sexy

“Elizabeth Stefanski is an impatient social innovation junkie with over a decade of experience in building and leading social ventures. She recently joined the Business Innovation Factory as chief market maker, where she is attracting capital and building partnerships to generate new models for transforming complex social systems. Stefanski also serves as advisor and gender-centric design expert to Bazaar Strategies, rolling out emerging market innovations in mobile technology.” - TEDx

5) Systems Thinking in a Digital World - Peter Senge

“Peter Senge explores how we have shifted in to a new generation of systems thinking. He asks us to think about how we use technology and how that technology influences, for better and worse, the ways we communicate and connect.” - Dalai Lama Center for Peace and Education

Additional Videos:

Into from the master Donella Meadows: In a World of Systems

Intro MIT course overview: Introduction to System Dynamics

Applying Systems Thinking by the Center for Disease Control: The Value of Systems Thinking

A Systems Story - Systems Thinking

Critique of Systems Thinking: I used to be a systems thinker

Organizational Systems Thinking: Systems Theory of Organizations

Maximize Program Effectiveness: Systems Thinking

Websites & Groups:

1) Systems Thinking, Systems Tools and Chaos Theory

“Three of the biggest breakthroughs in how we understand and successfully guide changes in ourselves, others and organizations are systems theory, systems thinking and systems tools. To understand how they are used, we first must understand the concept of a system. Many of us have an intuitive understanding of the concept. However, we need to make that intuition even more explicit in order to use systems thinking and systems tools.”

2) The Systems Thinker

“With the launch of thesystemsthinker.com, we hope to drive much broader adoption of this insightful material. Our intention is for the site to be an archive of already published material. At this time, we’re not planning on publishing new material.”

3) The Donella Meadows Project: Academy for Systems Change

“The mission of the Donella Meadows Project is to preserve Donella (Dana) H. Meadows’s legacy as an inspiring leader, scholar, writer, and teacher; to manage the intellectual property rights related to Dana’s published work; to provide and maintain a comprehensive and easily accessible archive of her work online, including articles, columns, and letters; to develop new resources and programs that apply her ideas to current issues and make them available to an ever-larger network of students, practitioners, and leaders in social change. Read More”

4) Waters Center for Systems Thinking

“The Waters Center for Systems Thinking is an internationally recognized leader in system thinking capacity building. We are dedicated to providing the tools and methods that help people understand, track, and leverage the connections that affect their personal and professional goals.”

What’s Next?

The next newsletter will be on Object Oriented Ontology (OOO), specifically the book by the same name written by Graham Harmon.

If you enjoyed this post, please share with other potential eclectic spacewalkers, consider subscribing or gift a subscription, or connect with us on social media to continue the conversation! Also, I am an advocate of Bitcoin. My address is on my About.Me page if you are feeling extra curious.

Subscribe to Substack Newsletter

Listen to all podcasts on Anchor

Follow Eclectic Spacewalk on Twitter

Thank You for your time. Until the next post, Ad Astra!